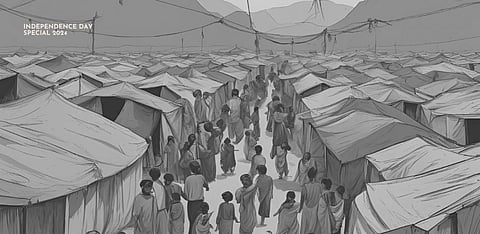

This Independence Day, a look at the status of refugees and asylum seekers in India and how they are left adrift of protection from non-refoulement.

—

ARTICLE 21 of the Constitution of India provides that no person shall be deprived of their life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.

In recent decades, this provision has been understood as more than a bare restriction on the executive. Instead, Article 21 has been interpreted as a broader guarantee of the right to live with human dignity, encompassing and protecting a wide array of substantive and procedural rights necessary to enjoy life and liberty.

But Article 21 falls short of its promises when it comes to protecting refugees and asylum seekers in India against refoulement (that is, removal to countries where they may face persecution).

“Article 21 falls short of its promises when it comes to protecting refugees and asylum seekers in India against refoulement.

On a consistent view, refoulement of a refugee or an asylum seeker is a clear breach of Article 21— it is the State's conduct directly jeopardising a person's life or liberty. Yet, India's courts have proven cautious and ineffectual in allowing Article 21 to protect the rights and safety of refugees and asylum seekers.

Also read: Citizenship's Rule of Exception

This piece examines how Indian courts have failed to use Article 21 to adequately protect refugees and asylum seekers in India. Moreover, judgments that have supposedly supported the right to non-refoulement have not provided clear or effective guarantees to people at risk of removal from India.

This, in turn, illustrates some fatal flaws within the Supreme Court's approach to Article 21— its inability to articulate the content and scope of that provision, and its baseless and damaging denial of protections under Article 21 to non-citizens.

India is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugees Convention or the 1967 Refugees Protocol. However, it is a signatory to other instruments which give rise to non-refoulement obligations, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Furthermore, India does not have a national 'refugee law' governing the status and rights of refugees. Instead, the protection of refugees is a matter of policy, including a 'standard operating procedure' which permits refugees to receive long-term visas in India.

This policy, in turn, works in concert with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)'s procedures for refugee status determination in India, assessing the claims of asylum seekers and granting refugee cards to those who need protection.

The fact that India does not have a national refugee law does not mean that Article 21 does not, or should not, extend to refugees.

What measures should be taken to guarantee a 'life with human dignity' may, in some circumstances, depend on previous promises made by the State. But it cannot solely depend on that.

Where a person is within India— and who hence enjoys the protections of the Constitution, except where the Constitution itself explicitly provides otherwise— and where the government intends to deprive that person of their life and liberty by deporting them to danger, it is no answer that there is no law governing this area.

Whether India returns people to States where they face treatment or punishment prohibited in India by Article 21 should not turn only on whether India has already made a commitment not to do so.

Article 21 has been taken to prohibit torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment as an absolute proposition, not merely to give effect to a statutory prohibition. Why should it then permit the Indian government to remove a person from India when this may cause a person to be tortured or harmed as a result?

In Louis De Raedt versus Union of India, Justice L.M. Sharma observed that the fundamental rights of foreigners "is confined to Article 21 for life and liberty and does not include the right to reside and settle in this country", a right under Article 19(1)(e) of the Indian Constitution "applicable only to the citizens of this country".

This observation arose in Louis de Raedt's particular and unusual circumstances. He was a Belgian who had lived in India since 1937 and challenged an Order for his removal from the country. The mere fact that Article 21 does not confer a right to reside does not answer the question of whether Article 21 prohibits refoulement, that is, a right not to be removed.

“The fact that India does not have a national refugee law does not mean that Article 21 does not, or should not, extend to refugees.

Similarly, Justice Vivian Bose's observation in Hans Muller versus Superintendent, Presidency Jail, Calcutta, that the Foreigners Act, 1946 "confers the power to expel foreigners from India", "vests the Union government with absolute and unfettered discretion" and confers "an unrestricted right to expel" is the beginning, not the end, of the inquiry.

Many statutes and powers are expressed in broad and ambulatory terms. That does not mean that those statutes create unreviewable constitutional states of exception.

Any statutory discretion is ultimately subject to outer limits imposed by the Constitution's prohibitions on certain forms of treatment or punishment, including arbitrary deprivation of life and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

In several cases, Indian high courts have affirmed that protection against non-refoulement forms part of Article 21. For example, the Gujarat High Court in Ktaer Abbas Habib Al Qutaifi & Anr. versus Union of India and the Delhi High Court in Dongh Lian Kham versus Union of India.

But what does the right against non-refoulement actually entail in the Indian context? It is not an absolute protection against removal. Even at its highest level, it provides that certain 'procedures' should be followed, that refugees' claims to remain in India should be reconsidered by the government, or that the government should consult with the UNHCR about other countries to which petitioners could be removed.

This, in turn, means that where 'reasonable procedures' have been followed, refugees can be removed from India, as established in the Delhi High Court's judgment in Mohammad Sediq versus Union of India.

What are 'reasonable procedures' in this context? The decision in Mohammad Sediq provides little explanation. Again, it is no answer that there is no Union 'refugee law' in India to spell out these procedures in detail.

If Article 21 only guarantees 'reasonable procedures' as a protection against refoulement, then the courts need to explain what those procedures are: does it include a right to be heard? In what way and by whom? According to what criteria? Unless these procedures are explained and given substance, the right to 'reasonable procedure' is a mere platitude.

The absence of 'reasonable procedures is linked' to broader failings within Article 21's jurisprudence to actually articulate what the clause stands for.

As Gautam Bhatia points out, Indian jurisprudence, Article 21 and the right to life include everything under the Sun, but the one thing it does not include is an individual's right to life.

A lack of clarity about Article 21's boundaries and its endless expansion into new fields grants courts far too much discretion in deciding whether the clause does or does not apply to a given case.

These observations set the context for the key ongoing controversy in the relationship between Article 21 and refugee non-refoulement— Mohammad Salimullah versus Union of India, the ongoing litigation about the removal of Rohingya refugees and asylum seekers from India.

“The right against non-refoulement is not an absolute protection against removal. Even at its highest, it provides that certain 'procedures' should be followed.

The government of India argues that it has the power to remove the seven Rohingya petitioners, all of whom have been recognised as refugees by the UNHCR, because their proposed removal is, "strictly in accordance with law, after following due process and in the larger interest of the country."

The government's reasoning illustrates that treating Article 21 as a mere 'procedural' guarantee does not limit the government's power to remove refugees from India; it only requires that they follow vague and unspecified procedures before removing them.

In its 2021 interlocutory judgment in Mohammad Salimullah, the Supreme Court rejected the petitioners' plea to pass a direction to prevent the deportation of Rohingya refugees detained in Jammu, thereby adopting an extremely narrow and outdated construction of Article 21.

The court's concluding observation reads: "The Rohingyas in Jammu, on whose behalf the present application is filed, shall not be deported unless the procedure prescribed for such deportation is followed," which illustrates the hollowness of a 'procedural' approach to Article 21.

It is not a right to non-refoulement, merely a protection against being refouled without following (unspecified and unclear) procedures. While this is only an interlocutory judgment, the eventual final judgment in Mohammad Salimullah may have significant (and severe) consequences for the protection of refugees in India.

In Mohammad Salimullah, the Supreme Court identified a 'substantial question' arising from the litigation as to whether illegal immigrants in India could be considered for recognition as refugees in India.

On one hand, this is a startling position: whether a person is a 'refugee' depends upon whether they have a well-founded fear of persecution in their country of origin, not on how they entered India.

“It is not a right to non-refoulement, merely a protection against being refouled without following (unspecified and unclear) procedures.

But it also illuminates a fundamentally destabilising and damaging aspect of the jurisprudence in this area: the artificial and baseless distinction drawn by the Supreme Court between rights to due process enjoyed by citizens of India and those enjoyed by non-citizens in respect of their removal from India.

As Darshana Mitra and Mohsin Alam Bhat have previously written for The Leaflet, in Sarbananda Sonowal versus Union of India, the Supreme Court drew a distinction between procedures in a criminal trial and "the matter of identification of a foreigner and his deportation" because in the latter, the person affected "is not being deprived of his life or personal liberty".

This distinction was used to exclude foreigners' deportation proceedings from the safeguards of fair, just and reasonable procedures which would otherwise protect citizens of India, ironically, within a regime in which foreigners are imputed with criminality and equated with criminals.

There is a clear relationship between the court's stance in Sarbananda Sonowal and the ongoing litigation in Mohammad Salimullah: both cases concern the notion that an individual's status as 'foreigner' should determine their entitlements under Article 21 and that perceived threats to national integrity take precedence over the safety of refugees.

There is nothing in the text or context of Article 21 to warrant either stance. Since the Supreme Court's verdict in Maneka Gandhi versus Union of India, Article 21 has been understood as a protection of the right to human dignity, assured both through fair, just and reasonable procedures and through prohibitions on certain forms of treatment.

Drawing artificial distinctions within the clause as to who truly 'deserves' the right to human dignity renders Article 21 itself meaningless and arbitrary.

On a consistent doctrinal approach, Article 21 of the Constitution of India should be understood to extend to include rights to non-refoulement from India, where a person's removal from India would expose them to a real chance of persecution (including, relevantly, arbitrary deprivation of life, torture or cruel or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment).

“Drawing artificial distinctions within the clause as to who truly 'deserves' the right to human dignity renders Article 21 itself meaningless and arbitrary.

The Supreme Court and the high courts have proven inconsistent and hesitant in recognising these rights. To merely treat these rights as 'procedural' in character is not a true protection against government action which may expose residents of India to forms of harm prohibited by the Constitution.

This article draws on the author's previous article accessible here.