Gandhi was convicted in a defamation case and subsequently disqualified from the Parliament. He has now filed an appeal against the order. He was recently granted bail and his sentence has been suspended till the final disposal of the appeal.

—

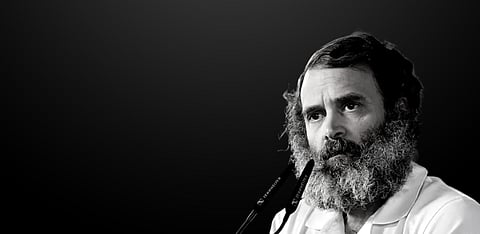

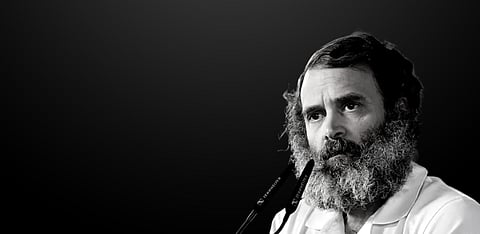

INDIAN National Congress leader Rahul Gandhi was granted interim bail yesterday by a sessions court in Surat after filing an appeal against the order by a chief judicial magistrate (CJM) in Surat of his conviction and sentence in a 2019 defamation case. He was convicted under Sections 499 (defamation) and 500 (punishment for defamation) of the Indian Penal Code.

The sessions court will hear the appeal against the conviction on April 13, and the application on regular bail will be heard on May 3.

He has been sentenced to two years, which is the maximum punishment for defamation, for the imputation, "How are the names of all these thieves Modi, Modi, Modi— Nirav Modi, Lalit Modi, Narendra Modi— and if you search a little, more Modis will spill out?", made during a rally in Kolar, Karnataka during the 2019 Lok Sabha election campaign.

His sentence has now been suspended till the disposal of the appeal.

Gandhi challenged the order of the trial court on the basis that it suffers from incurable defects and is incapable of being sustained. He has requested a stay of the order under Sections 389 and 389(1) (suspension of sentence pending the appeal; release of appellant on bail) of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC).

One of the grounds for appeal is that the defamation complaint was not maintainable because the complainant, Gujarat legislator Purnesh Modi, is not an aggrieved person.

The CJM gave two reasons for finding that the complainant was competent to file a complaint: first, that he was shocked and his reputation was hurt, and second, persons identified as Modi or whose surname is Modi have been defamed.

As far as the offence of defamation is concerned, under Sections 499 and 500, only 'some person aggrieved by the offence' can file a complaint under Section 199(1) (prosecution for defamation) of the CrPC.

The single imputation that "why do all thieves have their surname as 'Modi''' has not been made against a determinate group of persons. The CJM erred in holding that the persons identified as Modis or whose surname is Modi had been defamed; thereby any complainant, being Modi, could file the complaint.

The CJM did not consider the ratio of judgments that have held that the 'collection of persons' defamed should be identifiable, definite, determinative and well-defined. He did not discuss whether the persons having the surname Modi or persons known as Modi fulfil those criteria. 'Modi' is not a specific community. There are, of course, Modis in every community, but they are not a determinate group of persons.

The CJM relied on the Supreme Court's judgment in Sahib Singh Mehra versus State of Uttar Pradesh (1965) to sustain the allegation of defamation against all Modis. But this judgment says that the collection of persons must be identifiable so that there is a certainty that a particular group of persons has been defamed as against the rest of the community.

The complainant terms the imputation to be against 'Modi samaj', which he says comprises 13 crore people, and therefore is a particular group of persons which was defamed as distinguished from the rest of the community.

However, there is no Modi samaj or any such community established on the record, as claimed by the complainant. There are specific communities carrying the 'Modi' surname, such as the Modi vanik samaj, the Modh gachi samaj and the Tel gachi samaj. The complainant cannot be defamed as a member of Modi samaj, though, when it does not exist.

It should also be noted that the CJM did not convict Gandhi based on this argument that the complainant, as a member of Modi samaj, has been defamed. It is only based on the defamatory imputation against 'Modis'.

The complainant's earlier surname was 'Bhootwala'. Subsequently he changed his surname to Modi in 1988. No certified copy has been produced to show that the surname had been changed.

Even if the alleged surname has been changed, the complainant goes by the surname of Bhootwala, as per the appeal.

There is no mens rea in the form of intention to harm or knowledge that it would harm. The CJM erred in believing that Gandhi, merely because he did not stop in his 2019 speech at naming Prime Minister Narendra Modi and fugitive businessmen Nirav Modi and Lalit Modi, intended to defame all persons named Modi.

Even if the imputation "why do all thieves have the surname 'Modi''' is taken to be proved, it merely suggests that the sentence was spoken in connection with Narendra Modi, Nirav Modi and Lalit Modi, and not every person named Modi.

The CJM erred in believing that any person who suffers pain or is shocked because of a defamatory imputation has the right to file a complaint. The imputation should be either hurled against them or a collection of persons of which the complainant is a member.

Moreover, barring one alleged sentence ("why do all thieves have their surname as 'Modi'''), all other alleged defamatory comments in that public address were against Narendra Modi. Gandhi addressed the Prime Minister as a thief for the substantial reason that the money of the poor people of the country was being given away to tycoons, according to the appeal.

Gandhi has the right to criticise and comment upon the measures undertaken by Narendra Modi as the Prime Minister. A critical opinion should not lead to defamation, his appeal argues.

The alleged imputation must be seen in its entirety and if seen in this manner, there appears to be no defamation.

The complainant has not given any legal evidence to prove defamation. He has merely relied on a WhatsApp image of a newspaper report by news agency IANS from Kolar, Karnataka where the imputation was made. Moreover, this evidence has not been proved before the CJM.

Then the complainant relies on the speech that he copied on a pen drive, which was not produced along with the complaint. It was only produced when the complainant happened to come for deposition before the CJM. The source and authenticity of the speech that was recorded and uploaded on YouTube remain questionable, and no certificate as required under Section 65B (admissibility of electronic evidence) of the Indian Evidence Act has been produced to prove this.

The maximum punishment granted to Gandhi led to his disqualification as a Member of Parliament (MP). A two-year sentence is a minimum needed under Section 8(3) (disqualification on conviction for certain offences) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, to disqualify an MP.

The disqualification of an elected representative essentially interferes with the choice of the electorate in a free and fair election, the appeal states.

Moreover, if the CJM's order is not stayed or suspended, a by-election shall be held by the Election Commission within the stipulated time at Gandhi's former Lok Sabha constituency, and this would lead to him forfeiting his right to represent the constituency for the remaining part of his tenure.

Disqualification under Section 8(3) of the 1951 Act also disentitles the elected representative from re-contesting the by-poll. Consequently, the electorate has to forgo the right to have a representative, who is truly representative of the majority of voters of the constituency. This loss is irreparable and even the subsequent acquittal of Gandhi cannot undo the same.

Additionally, the by-election would lead to an enormous burden on the state exchequer.

Moreover, the excessive sentence of two years is not only unprecedented and contrary to the existing law on this subject, but is also unwarranted in the present case which has overriding political overtones. The harshest possible sentence was chosen predominantly because Gandhi was an MP, his appeal states. The CJM inferred that as an MP, he should have known the effects of the words allegedly used by him.

Lastly, there was a lack of jurisdiction at the time of summoning Gandhi, and the mandatory provisions of inquiry under Section 202 (postponement of issue of process) of the CrPC had been forgone, leading to material infirmities. Where an accused resides outside the jurisdiction of the court, an inquiry before issuing the process is mandatory. 'Inquiry' means that witnesses have to be examined and reasons should be stated as to why the process has been issued.

Reliance has been placed by the appeal on Supreme Court judgments in Deepak Gaba & Ors. versus State of Uttar Pradesh & Anr. (2023) and Abhijit Pawar versus Hemant Madhukar Nimbalkar (2016).

In Deepak Gaba, the Supreme Court in paragraph 22 observed, "While summoning an accused who resides outside the jurisdiction of court, in terms of the insertion made to Section 202 of the Code by Act No. 25 of 2005, it is obligatory upon the Magistrate to inquire into the case himself or direct investigation be made by a police officer or such other officer for finding out whether or not there is sufficient ground for proceeding against the accused. In the present case, the said exercise has not been undertaken."

Even in Abhijit Pawar, it was held, "Admitted position of law is that in those cases where the accused is residing at a place beyond the area in which the Magistrate exercises his jurisdiction, it is mandatory on the part of the Magistrate to conduct an enquiry or investigation before issuing the process. Section 202 of the Cr.P.C. was amended in the year by the Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act, 2005, with effect from 22nd June, 2006 by adding the words 'and shall, in a case where the accused is residing at a place beyond the area in which he exercises his jurisdiction."

It further added that "[t]here is a vital purpose or objective behind this amendment, namely, to ward off false complaints against such persons residing at a far off places in order to save them from unnecessary harassment…."

In these cases, it has also been held that the whole proceedings become void if this provision is not complied with. The CJM erred in holding that these judgments will not apply Gandhi has not challenged the initial order of issuance of summons under Section 482 (saving of inherent power of the high court) of the CrPC, because non-compliance with this provision can be raised at any stage of the proceedings.

In view of the above reasons, Gandhi's conviction is erroneous, patently perverse, and in flagrant violation of principles of appreciation of evidence in a criminal trial, claims the appeal.