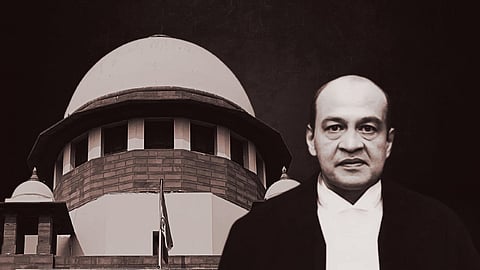

IN A MAJOR SETBACK for Allahabad High Court judge Justice Yashwant Varma, the Supreme Court on Friday rejected his petition challenging the decision of the Lok Sabha Speaker to admit a motion for his removal as a High Court judge and to constitute a three-member inquiry committee under the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968 to investigate allegations against him.

A two-judge bench comprising Justice Dipankar Datta and Justice Satish Chandra Sharma found no infirmity in the Speaker's decision.

The allegations against Justice Varma relate to the alleged recovery of unaccounted cash by Delhi Fire Service personnel on March 14, 2025, from an outhouse at his official residence during a firefighting operation.

Before the Supreme Court, Justice Varma contended that the Speaker could not have constituted the committee unilaterally because notices for his removal had been given in both Houses of Parliament on the same day.

He relied on the first proviso to Section 3(2) of the Judges (Inquiry) Act, which contemplates a situation where notices are given in both Houses on the same day. In such a case, "no committee shall be constituted unless the motion has been admitted in both Houses; and where such motion has been admitted in both Houses, the committee shall be constituted jointly by the Speaker and the Chairman".

Timeline of events

Justice Datta, in his judgment, noted the following facts:

On July 21, 2025, a notice of motion signed by more than 100 members of the Lok Sabha, seeking to present an address to the President for the removal of Justice Varma, was prepared and received by the Speaker at 12:30 p.m., but it was not admitted on the same day.

Between 4:07 p.m. and 4:19 p.m. on the same day, a notice for the same purpose, signed by more than 50 members, was submitted in the Rajya Sabha. The then Chairperson of the Rajya Sabha noted that a similar notice may have been given in the Lok Sabha and directed that "the Secretary-General will take necessary steps in this direction". Chairperson Jagdeep Dhankhar resigned on the evening of July 21, 2025.

On August 11, 2025, the notice submitted in the Rajya Sabha was scrutinized by its Secretary-General, who observed various deficiencies and held it to be not "in order". The draft decision of the Secretary-General was placed before the Deputy Chairman, who was discharging the functions of the Chairperson in his absence. The Deputy Chairman concurred and recorded that the notice was "not admitted". This decision was communicated to the Secretary-General of the Lok Sabha on the same day.

On August 12, 2025, the Speaker of the Lok Sabha proceeded to admit the notice given in the Lok Sabha on July 21, 2025.

Five key issues

Justice Datta framed five issues for determination:

How should the first proviso to Section 3(2) of the 1968 Act be construed? Does it require the constitution of a joint committee where notices, having been given in both Houses on the same day, are later followed by refusal to admit the motion by the Presiding Officer of one House and admission of the motion by the Presiding Officer of the other House?

Whether, in view of the office of the Chairman of the Rajya Sabha falling vacant, the Deputy Chairman of the Rajya Sabha was competent to refuse admission of the notice of motion?

What is the effect, if any, of the Deputy Chairman's refusal to admit the motion on the validity of the Speaker's action under Section 3(2) of the 1968 Act?

Whether the draft decision prepared by the Secretary-General of the Rajya Sabha, recording that the notice of motion given to the Chairman was not "in order", was justified in law?

Whether the petitioner is entitled to any relief?

Interpretation of the first proviso

Regarding the first issue, it was argued on behalf of Justice Varma that where notices of motion have been given in both Houses on the same day, the rejection of the notice in one House would automatically invalidate the notice in the other House. The bench rejected this argument for the following reasons:

First, the first proviso to Section 3(2) of the 1968 Act does not address all possible permutations but is confined to one specific situation: where notices of motion given in both Houses on the same day have been admitted in both Houses. Only in that limited situation does the statute mandate the constitution of a joint committee. The proviso does not prescribe a condition precedent for the formation of a committee in cases other than the one expressly provided.

Second, nothing in the 1968 Act suggests that rejection of a motion in one House renders the other House incompetent to proceed in accordance with law. Had Parliament intended such far-reaching consequences, it would have articulated the first proviso in clear and unambiguous terms.

Third, the interpretation advanced by Justice Varma would produce absurd results, making the individual capacity of one House to initiate a motion under Article 124(4) contingent upon the outcome in the other House, even at the stage of admission. Removing the autonomy of one of the two Houses of Parliament could not have been the intent behind the first proviso.

Fourth, such an interpretation would render the first proviso susceptible to abuse. It would permit a situation where, upon learning of a notice of motion likely to be admitted by the Presiding Officer of one House, certain members of the other House, opposed to the removal process, could deliberately submit a defective notice on the same day solely to scuttle the proceedings.

It was also argued that the proviso confers an additional layer of protection on a judge by ensuring that if either House is unwilling to admit the motion, the impeachment process must fail.

The bench rejected this contention as well, observing that the protection afforded to a judge remains fully intact: even where a motion is admitted and a committee is constituted, either House retains absolute authority to reject the motion after the committee's report is placed before it. The bench emphasized that the proviso could not be interpreted in a manner that renders the removal mechanism practically unworkable.

"Constitutional safeguards for judges cannot come at the cost of paralyzing the removal process itself. The first proviso must, therefore, be construed to balance the prescribed protection with the effective functioning of the mechanism for removal of a judge from office, triggered by the people's representatives, and not to frustrate it altogether," the bench held.

On the first issue, the bench ruled that the first proviso to Section 3(2) applies only when notices of motion were given in both Houses on the same day and were admitted by both Houses (irrespective of whether admission occurred on the same or different dates).

Where notices were given in both Houses on the same day but the notice is not admitted in one House, a joint committee is not mandated, and the Speaker or the Chairman, as the case may be, may independently proceed to constitute a committee.

Deputy Chairman's competence

On the second issue—the competence of the Deputy Chairperson to deal with the notice of removal, much less its rejection—it was argued by Justice Varma that only the Chairperson could have done so, and not the Deputy Chairperson acting as Chairperson.

To buttress the argument, Justice Varma referred to Section 2(a) of the Judges (Inquiry) Act, which defines "Chairman" as the Chairman of the Council of States. It was thus contended that the legislature's use of the word "means" (and not the phrase "means and includes") suggests that the definition is exhaustive. Thus, the Deputy Chairperson could not have usurped the statutory power vested in the Chairman of the Rajya Sabha and acted in his place.

Reference was also made to certain rules made under the Judges (Inquiry) Act to contend that these rules confer authority on the Deputy Chairperson only in limited and specified circumstances, and do not extend to the exercise of powers contemplated under Section 3 of the Inquiry Act.

It is important to note that, as per Article 91, while the office of Chairman is vacant, or during any period when the Vice-President is acting as, or discharging the functions of, President, the duties of the office are performed by the Deputy Chairman or, if the office of Deputy Chairman is also vacant, by such member of the Council of States as the President may appoint for the purpose.

The bench also observed Rule 7 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in the Council of States, framed under Article 118, which provides that the Deputy Chairman is elected by the members of the House. Rule 9 of the Rules of Procedure further delineates the powers of the Deputy Chairman, which reads: "The Deputy Chairman or other member competent to preside over a sitting of the Council under the Constitution or these rules shall, when so presiding, have the same power as the Chairman when presiding over the Council and all references to the Chairman in these rules shall in these circumstances be deemed to be references to any such person so presiding."

The bench rejected Justice Varma's argument on the second issue that the Deputy Chairman could not have rejected the notice for removal.

The bench observed that there was no reason why Article 91 should be disregarded when a court is tasked with making a meaningful interpretation of any provision of the Inquiry Act or, for that matter, any other enactment.

After all, the bench said, the Constitution is the supreme law of the land and all laws validly enacted owe their origin to the Constitution.

"The duties that the Chairman and the Deputy Chairman (in case of a vacancy in the former office) perform under the Inquiry Act cannot be separated from the office that they hold as the Presiding Officer of the House," the bench ruled.

On the second issue, another contention was raised by Justice Varma. It was argued that the Deputy Chairman might himself be a signatory to the notice. The bench was not impressed by the argument and provided two reasons:

First, assuming that the Deputy Chairman happens to be a signatory to the motion, he must, as a matter of administrative prudence, recuse himself from acting as Deputy Chairman in that case. After all, the Rules of Procedure of the Rajya Sabha, under Rule 8, provide for a panel of Vice-Chairmen to be nominated by the Chairman, who would act in the absence of both the Chairman and the Deputy Chairman.

Second, if such a situation were to arise, the doctrine of necessity could also compel the Deputy Chairman—or whoever is the incumbent acting in place of the Chairman—to exercise the functions of the Chairman.

The bench also observed that if Justice Varma's argument were accepted on this point, it would create a constitutional vacuum which, in the absence of the Chairman of the Council of States or the Speaker of the House of the People (as the case may be), would render the provisions of the Inquiry Act otiose in the given circumstances.

The bench thus returned a finding on the second issue, holding that the Deputy Chairman was competent to consider the notice and refuse admission of the motion.

Effect of Deputy Chairman's decision

On the third issue—the effect, if any, of the Deputy Chairman's refusal to admit the motion on the validity of the Speaker's action under Section 3(2) of the Inquiry Act—the bench held that even if the Deputy Chairman's act were held illegal and consequently set aside, or a reconsideration ordered, it would not result in restoration of the status quo ante.

The bench also observed that even such a limited declaratory relief could not be granted under Article 32.

The bench opined that, upon valid admission of the motion by the Speaker, members of the Lok Sabha acquired a statutory entitlement to have the matter examined by a duly constituted committee. To interpret the statute in a manner that nullifies this entitlement owing to procedural infirmities (assumed or real) in the other House would amount to curtailing the participatory rights of elected representatives without statutory warrant.

The bench also noted that members of the Rajya Sabha suffered no prejudice from the Speaker's action. They had a right in law to insist that the notice given in the Rajya Sabha be dealt with in accordance with law by the competent authority. If they felt prejudiced, the Deputy Chairman's decision refusing to admit the motion could have been challenged by them.

"We assume that they did not prefer to challenge the decision because their purpose of having an inquiry conducted under the Inquiry Act stood fructified once the Speaker admitted the motion of the Lok Sabha members and constituted the committee," the bench underscored.

The bench further held that no prejudice was caused to Justice Varma by the Deputy Chairman's decision. It also observed that there was no challenge to the Deputy Chairman's decision in the petition filed by Justice Varma.

Secretary-General's role scrutinized

On the fourth issue, whether the draft decision prepared by the Secretary-General of the Rajya Sabha, recording that the notice of motion given to the Chairman was not "in order", was justified in law—although the examination of this issue was merely academic, the bench considered it. This issue arose because the bench noticed from the file notes that the Secretary-General had termed the notice not "in order" and had even gone into its merits.

The bench observed that there appeared to be an insistence on the use of "proper terms" for the notice—a requirement which finds no express recognition in law. It also noticed that a requirement seemed to have been read into the law for furnishing authenticated documents in support of the material facts, which, particularly in view of documents already in the public domain, may not have been necessary at that stage.

It observed that there was no statutory obligation on the notice-givers to produce supporting evidence at that juncture. It also flagged that the Secretary-General's note took exception to an incorrect reference to a statutory provision, without due appreciation of the legal position governing the subject.

More importantly, the bench underscored that the Secretary-General appeared to have examined the correctness of the facts pleaded, including with reference to certain dates, thereby traversing beyond the scope of his designated role. It held that the Inquiry Act does not contemplate a substantive assessment of the merits of the allegations by the Secretariat of a House. The Secretary-General's role was expected to remain confined to administrative scrutiny, such as verification of procedural compliance, and could not extend to assuming a quasi-adjudicatory function.

The bench pointed out that neither the Inquiry Act nor the rules framed thereunder prescribe a mandatory form for a notice of motion. "In the absence of defined parameters, it is not readily apparent on what basis the Secretary-General concluded that the notice of motion was not in order," the bench observed. It held that the role of the Secretary-General was confined to placing the notice before the competent authority—namely, the office of the Chairman—without expressing any conclusion as to its admissibility.

Eventually, the bench answered the last question in the negative as well. It held that Justice Varma was not entitled to any relief under its extraordinary jurisdiction under Article 32.