Modaks and laddoos fly in this delectable tale of executive–judiciary bonhomie.

—

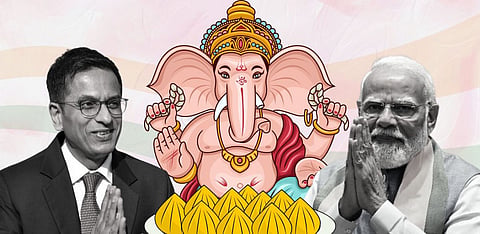

IN a historic yet festive moment, the incumbent Chief Justice of India (CJI) Dr D.Y. Chandrachud, who is set to retire on November 10 this year, extended a unique invitation to Prime Minister Narendra Modi for Ganesh Chaturthi at his residence.

Was this just a friendly celebration of divine pachyderm worship, or was it a subtle legal negotiation cloaked in modak-filled camaraderie? His delightful gesture left legal experts scratching their heads and wondering: is this a new precedent in judicial-executive relations, or just an epic way to mix law with laddoos?

First things first, inviting a Prime Minister to your home is no small feat. But inviting him to a Ganesh Chaturthi celebration? That is like inviting someone to a dinner party and serving only the finest constitutional paan and modaks.

Some might argue this could be a strategic move in judicial diplomacy, but let us be real. It is more likely that CJI Chandrachud just wanted to see if Modi could handle his spiciest sambhar, a South Indian dish befitting a leader who aspires to be the leader of the Global South.

“Article 50 of the Indian Constitution, which mandates the separation of powers between the judiciary and executive, may need revision. After all, nothing separates better than a plate of laddoos and modaks, right?

Could a sitting CJI invite the head of the executive branch for festive dharma at his humble abode? Was this a mere celebration, or an elaborate attempt to establish jurisprudence on inter-institutional Ganesh festivities?

Article 50 of the Indian Constitution, which mandates the separation of powers between the judiciary and executive, may need revision. After all, nothing separates better than a plate of laddoos and modaks, right?

Perhaps, in the spirit of Ganesh Chaturthi, this invitation was an experiment in amicus modakus— an experiment in the court making friends in the executive through modaks?

It is rumoured that upon entering CJI Chandrachud's residence, the Prime Minister was greeted with the Supreme Court's emblem strategically placed next to Lord Ganesha. An oversized scale of justice hung from the ceiling— balanced, of course, by garlands on one side and constitutional texts on the other.

One might wonder if the décor itself sent a message: Lord Ganesha, known for removing obstacles, was perhaps the perfect symbol for clearing the path between judicial activism and executive orders. There, between the incense and aarti, Modi may have realised that the real obstacle might not be electoral politics but clearing backlogs of pending cases.

As tradition would have it, Lord Ganesha must be offered modaks. But when it comes to a high-profile judicial-executive meet-and-eat, the choice of offerings itself can trigger constitutional debates.

Was this a subtle form of judicial review? By offering the Prime Minister a generous helping of modaks, was CJI Chandrachud signaling a willingness to review and perhaps sweeten executive actions? Or was it simply a strategic way of suggesting that the executive, like the modak, should maintain its filling of power but remain wrapped within the confines of legality?

“Of course, Article 21's right to life would naturally extend to a right to dessert, making this offering not just a symbolic gesture, but a fundamental right under modak justice.

Of course, Article 21's right to life would naturally extend to a right to dessert, making this offering not just a symbolic gesture, but a fundamental right under modak justice.

As the Prime Minister and the CJI exchanged pleasantries, it was not long before the conversation inevitably veered toward constitutional issues. Lord Ganesha's large ears, ever attentive to matters of State and justice, must have perked up at the mention of judicial reforms.

Also read: Retiring milord's options

Perhaps, in between bites of Ganesh-shaped laddoos, the CJI casually proposed speeding up judicial appointments— a prayer as ancient as Indian democracy itself.

The Prime Minister, with a sage nod, might have responded with the ultimate judicial counterpoint: "All things in due process, just as Ganesh Chaturthi comes after careful preparation of the pandal."

Indeed, the judiciary's mantra of patience would have blended well with Lord Ganesha's wisdom, ensuring that any requests for judicial expedience were met with constitutional restraint.

As the festivities drew to a close, Lord Ganesha undoubtedly left the scene, his work done, leaving behind a strengthened understanding between the executive and judiciary.

Modi, with a tilak on his forehead and a packet of prasad in hand, may have departed with a newfound respect for the art of judicial diplomacy. After all, in the court of public opinion, a well-timed invitation, flavoured with festivity, might just remove more obstacles than any judgment in a court of law.

“As the festivities drew to a close, Lord Ganesha undoubtedly left the scene, his work done, leaving behind a strengthened understanding between the executive and judiciary.

As for the rest of us, we can only hope that this Ganesh Chaturthi marks the beginning of a new constitutional tradition— where the judiciary and executive, under Lord Ganesha's watchful eyes, come together for justice, unity and modaks for all.

While Article 50 may not explicitly mention the sharing of sweets between institutions, it is safe to assume that Lord Ganesha, the remover of obstacles, would bless such a delicious breach of protocol.