The Adani Group has alleged that author and senior journalist Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, and his co-writer used anonymous sources in their articles. However, the only anonymous source is an "unnamed spokesperson" of the Adanis, whose comments defend the Adani Group and were reproduced verbatim, says The Leaflet Staff Writer MONICA DHANRAJ.

——-

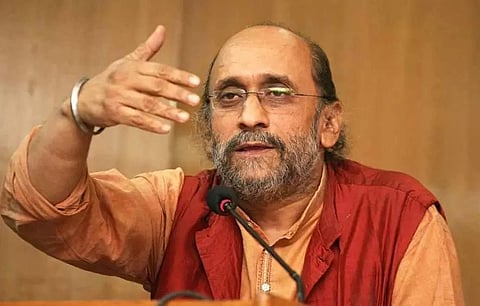

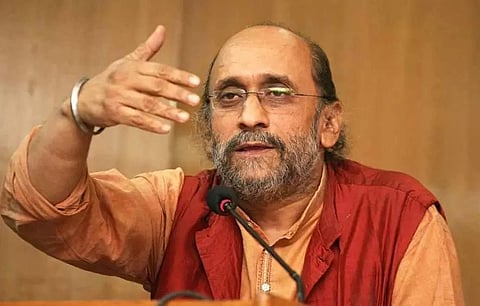

ON January 19, a court in Gujarat's Kutch district issued an arrest warrant against author and senior journalist, Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, in a criminal complaint on defamation under Section 500 of Indian Penal Code that was filed by the Adani Group in 2017. Issuing directions to the Nizamuddin Police Station in New Delhi, Judicial Magistrate, Pradeep Soni, said Thakurta, "who stands charged with a complaint under Section 500 [defamation] of Indian Penal Code" should be arrested.

In June of 2017, the Adani Groups lawyers wrote to Economic and Political Weekly objecting to the contents of an article published on January 14, 2017, demanding for unconditional retraction and removal or deletion of another article published by EPW on June 24, 2017, for allegedly being defamatory and harmful to the reputation of the Adani group. The article was removed by EPW after Sameeksha Trust, which owns and runs the journal, ordered the editorial department to take the article down. The Wire republished both articles at the time of their original publication in EPW and received similar communication from the Adani lawyers to take down the second article.

The Wire continued to host the article on its website which led the Adani group to file a civil defamation suit in Bhuj and a criminal defamation complaint in Mundra against The Wire, its editors and the authors of the article. In November 2018, the Principal Senior Civil Judge of Bhuj rejected the application for an injunction in the civil defamation suit. The court ruled that the article could stay on The Wire's website, subject to removal of a sentence and an adverb.

With respect to the criminal defamation complaint, Adani withdrew all legal proceedings in May 2019, against all the accused, except Thakurta.

In September 2020, the Adani Group filed another set of criminal defamation complaint and civil defamation suit, in courts in Ahmedabad against Thakurta. The complaint and the suit were in relation to a series of two articles written by Thakurta and co-author, Abir Dasgupta and published by the digital news organisation, Newsclick on its website on August 7, 2020, and September 7, 2020. This suit and the complaint named Newsclick, its editors, Paranjoy Guha Thakurta and his co-authors, as defendants/accused.

The piece by Thakurta and Dasgupta discussed eight Supreme Court cases since 2019 which involved the Adani group. Each case was heard by a bench headed by Justice Arun Kumar Mishra. When the first part article was published on August 7, the Supreme Court had already delivered judgments in six of them. All six had been in favour of the Adani Group.

In their first article, the authors discussed the factual matrix and socio-political context of the six judgments. They also laid out details of the seventh case involving the Adani Group, which at the time of publication was pending before a bench headed by Justice Mishra.

“Rule 3A of Order XXXIX of the Code of Civil Procedure mandates that when an ex-parte injunction is granted by the court, the court shall endeavour to finally dispose of the injunction application within thirty days of the date on which the injunction was granted and record its reasons where it is unable to do so.

On August 31, 2020, the Supreme Court delivered its judgment in the seventh case, awarding the Adani Group subsidiary, Adani Power Rajasthan Limited (APRL), "compensatory tariffs" worth thousands of crores from the state of Rajasthan. A week later, on September 7, Newsclick published the second article, discussing this judgment.

On September 14, 2020 the Adani Group, through Adani Power Rajasthan Limited (APRL or the "Plaintiff" ), filed a complaint of criminal defamation in the court of the Chief Metropolitan Magistrate, Ahmedabad, followed, on the 15th of September, by a civil defamation suit at City Civil Court, Ahmedabad, against Newsclick, its editors and the authors of the piece. The suit sought damages worth Rs.100 crore. The Adani group also filed an injunction application seeking, inter alia, a temporary injunction on the defendants from publishing anything defamatory to APRL or the Adani Group.

APRL's 24-page application for injunction mentions that the statements of the authors were defamatory because the articles "build a narrative based on fictitious nexus for the judicial pronouncement" and that it was a "classic example of trial by media where information gathered from anonymous sources are used to make distasteful personal attacks on reputable business leaders who have built and manage critical assets for the country".

The Adani Group company has also contended that the article "questions the integrity of the plaintiff and the entire apex judicial establishment of the country" on the basis of a quotation from an anonymous person and parts of the article were defamatory because they were based on the assumption of an anonymous expert.

In addition, it alleged, at multiple places in the injunction application, that statements from the articles were not only defamatory of the plaintiff but amounted to contempt of court. The relevance of alleging contempt of court in an application which is meant to establish a prima facie case of APRL's defamation is unclear. The injunction application alleges repeatedly that the authors of the article use anonymous sources and experts to make their arguments. However, the only anonymous person in the piece is an "unnamed spokesperson" of the Adanis, whose comments defend the Adani Group. He is quoted verbatim in the article, without being named.

Thus, the article fulfils a basic tenet of fair journalism to afford all stakeholders of a journalistic piece an opportunity to comment. Other than the unnamed spokesperson, everything the authors say in their articles is substantiated by them with sources on the record and hyperlinks to other publications which have recorded the developments they mention.

On September 19, 2020, the City Civil Court at Ahmedabad granted an ex-parte interim injunction against the defendants "in terms of paragraph 34(a) of the injunction application" filed by the Adani Group.

It is important to examine the contents of paragraph 34(a) of Adani's injunction to understand this order. The plaintiff makes the following prayer to the court:

"Pending hearing and final disposal of the suit, the honourable court be pleased to pass an order of temporary injunction to restrain the defendants, their servants, agents, or representatives from in any manner stating publishing, issuing, circulating, distributing, carrying out reports or articles or reporting of any kind, directly or indirectly, in any manner whatsoever either in print or electronic or any other form of media, any defamatory story or article concerning the plaintiff company and Adani group and, from further making publishing circulating or causing or authorising to be published and circulated the words complained of or similar defamation material relating to the plaintiff company and Adani group."

An interim injunction is a special discretionary relief in law and therefore, comes with its own stipulations. Under provisions of Order XXXIX of the Code of Civil Procedure(CPC), 1908 the party seeking the interim injunction has to establish- a prima facie case, the irreparable loss that would be caused in case of denial to grant relief and, the balance of convenience in his favour.

In Best Sellers Retail India v. Aditya Birla Nuvo Ltd, the Supreme Court observed that prima facie case alone is not sufficient to grant an injunction, holding :

"…the settled principle of law is that even where [a] prima facie case is in favour of the plaintiff, the Court will refuse temporary injunction if the injury suffered by the plaintiff on account of refusal of temporary injunction was not irreparable."

The Supreme Court in Gurudas and Ors. Vs. Rasaranjan summarized the same, holding:

"While considering an application for injunction, the Court would pass an order thereupon having regard to prima facie case, balance of convenience and irreparable injury"

Like, I mentioned before, an interim injunction is a special remedy; but an ex-parte interim injunction an exceptional one. It is established law that an injunction granted by the court without giving notice to the opposite party must be done with sound judicial discretion.

Order XXXIX Rule 3 of the Code of Civil Procedure(CPC), 1908 provides for ex-parte temporary injunction in the cases of extreme urgency and Rule 3A of Order XXXIX of the CPC mandates that when an ex-parte injunction is granted by the court, the court shall endeavour to finally dispose of the injunction application within thirty days of the date on which the injunction was granted and record its reasons where it is unable to do so.

“The article fulfils a basic tenet of fair journalism to afford all stakeholders of a journalistic piece an opportunity to comment. The writers seem to have done exactly that. Other than the unnamed spokesperson, everything the authors say in their articles is either in the public domain or is substantiated by them with sources on the record, and hyperlinks to other publications which have recorded the developments they mention.

Explaining the consequences of a court not proceeding in accordance with Rule 3A, the Supreme Court in A. Venkatasubbiah Naidu v. S. Chellappan observed:

"…in such a case the Court would have by-passed the three protective humps which the legislature has provided for the safety of the person against whom the order was passed without affording him an opportunity to have a say in the matter…the Court is obliged to give him notice before passing the order. It is only by way of a very exceptional contingency that the Court is empowered to by-pass the said protective measure.

Second is the statutory obligation cast on the Court to pass final orders on the application within the period of thirty days. Here also it is only in very exceptional cases that the Court can by-pass such a rule in which cases the legislature mandates on the Court to have adequate reasons for such bypassing and to record those reasons in writing. If that hump is also bypassed by the Court it is difficult to hold that the party affected by the order should necessarily be the sole sufferer."

In addition, an ex-parte order must be for a stipulated period, as noted by the Supreme Court in the case of Morgan Stanley Mutual Fund v. Kartick Das. The Court, held, inter alia that

"As a principle, ex parte injunction could be granted only under exceptional circumstances.

The factors which should weigh with the court in the grant of ex parte injunction are-

(a) whether irreparable or serious mischief will ensue to the plaintiff;

(b) whether the refusal of ex parte injunction would involve greater injustice than the grant of it would involve;

(c) the court will also consider the time at which the plaintiff first had notice of the act complained so that the making of improper order against a party in his absence is prevented;

(d) the court will consider whether the plaintiff had acquiesced for some time and in such circumstances it will not grant ex parte injunction;

(e) the court would expect a party applying for ex parte injunction to show utmost good faith in making the application.

(f) even if granted, the ex parte injunction would be for a limited period of time.

(g) General principles like prima facie case, balance of convenience and irreparable loss would also be considered by the court.

Equally importantly, an ex-parte injunction, once granted, is quite difficult to vacate as has been observed by courts, including the Delhi High Court, in the Microsoft Corporation v. Dhiren Gopal, in which the court remarked:

"There is no gainsaying that once an ex-parte injunction is granted by the Court, getting an ex-parte injunction vacated or a decision on the application on merits by the court becomes a Herculean task for the other party."

It therefore becomes even more important that courts grant ex parte injunctions, only in exceptional circumstances.

A simple reading of the two articles by Thakurta and Dasgupta would show that it laid out meticulously the Supreme Court judgements involving the Adanis and placed them in their relevant social and political contexts to provide a complete picture of the events around these judgements. The ex-parte interim injunction against them, in terms paragraph 34(a) and without any time stipulated for its operation leaves the journalist-authors and Newsclick (and its editors) in a limbo with respect to reporting on the Adanis. The injunction order does not restrict the defendants from publishing about the Adani Group but from publishing "any material defamatory to APRL or the Adani Group."

The injunction order dated September 19, 2020, is peculiar. The judge is bound to make a prima facie determination on the alleged defamatory imputation. However, the order did not indicate or record that a prima facie case of defamation was made out prior to the grant of the injunction The order does not stipulate any time period for the operation of the injunction either, despite a catena of Supreme Court judgements holding otherwise.

The injunction order, in terms of a vague paragraph 34(a) of the injunction application, creates further problems with interpreting the order. Paragraph 34(a) of the interim application seeks injunction with respect to "any defamatory matter" which is problematic since the court can only grant injunction with respect to the defamatory imputation(s) set out in the plaint. The lack of any time stipulations for the operation of the injunction combined with the vague language of paragraph 34(a) gives the impression that the order seeks to bar all future reporting of the Adanis by Newsclick unless in glowing terms. Can such an order be enforceable in law? You decide.

(Monica Dhanraj is a lawyer and staff writer with The Leaflet. The views are personal.)