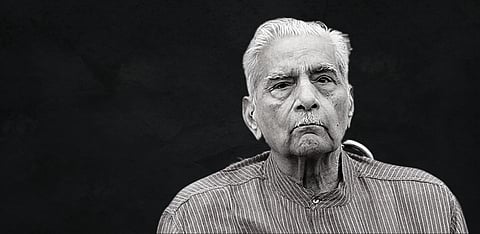

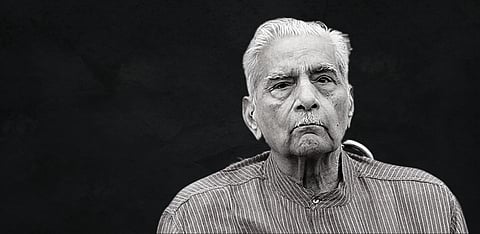

Crusader of justice and civil liberties, former union law minister and senior advocate Shanti Bhushan was known as a man of many firsts. Bhushan fought for the rule of law and to preserve the basic tenets of the Constitution. He passed away on January 31, at the age of 97 years, following a brief illness.

—-

IN the darkest hour of India's political history, when the draconian national emergency was imposed, not many stood up to protect the rule of law. But veteran senior advocate and former Union Law Minister Shanti Bhushan, who passed away on Tuesday, did.

Bhushan rose to fame when he fought against the powerful politician and then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, representing freedom fighter and politician, Raj Narain, in an election petition challenging Gandhi's election to the Lok Sabha on the grounds of malpractice. No political leader is above the law, he had told the court.

In a powerful judgment that shook the nation, the Allahabad High Court's Justice Jagmohan Lal Sinha convicted Gandhi of having committed electoral fraud and declared her election void, and also disqualified her from contesting elections for a period of six years from the date of the order.

Bhushan also challenged the Constitution (Thirty-ninth Amendment) Act, 1975, which inserted Article 329A into the Constitution, on the grounds that it destroys the basic structure of the Constitution, including judicial review and free and fair election. Clause 4 of Article 329A, which disallowed the election of the Prime Minister to be challenged before a court of law, was held unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

Bhushan constantly strove to preserve the tenets of the Constitution. When the Allahabad High Court's judgment led to political upheaval and ultimately triggered Gandhi to proclaim a national emergency, Bhushan fought to protect the fundamental right to free speech and liberty of detained opposition leaders in the infamous ADM Jabalpur versus Shivkant Shukla (1976) case. However, the majority of the Supreme Court's Constitution bench held that no habeas corpus petition is maintainable during an Emergency, since rights under Articles 19 and 21 of the Constitution were suspended. Only Justice H.R. Khanna, in his remarkable dissent, held otherwise. The judgment now stands overturned.

Bhushan was initially a member of the Indian National Congress (Organisation) party, but later joined the Janta Party. In 1980, he joined the Bharatiya Janata Party, but soon resigned. He then became a founding member of the Aam Aadmi Party.

As Union Law Minister in the Janata Party-led Union Government from 1977 to 1979, Bhushan introduced the Constitution (Forty-Fourth Amendment) Act, 1978, which repealed many provisions of the Constitution (Forty-Second Amendment) Act, 1976 and upheld the basic features of the Constitution, including judicial review.

He was also known as a champion of minority rights. In 1977, politician B.P. Mandal, who headed the Socially and Educationally Backward Classes Commission to identify socially and educationally backward classes, along with some parliamentarians wrote a letter to Bhushan, regarding the appointment of judges from backward classes to the Patna High Court. Bhushan wrote back, promising to look into the matter. Today, judges from backward classes are also appointed to courts.

Bhushan, along with his son, renowned public interest lawyer Prashant, continued to take up cases concerning public interest. During the contempt of court proceedings initiated against Prashant Bhushan for his interview in the Tehelka magazine relating to allegations of corruption against sitting judges of the Supreme Court, Shanti Bhushan filed an affidavit alleging that eight of the last 16 former Chief Justices of India were corrupt. The case was eventually dismissed.

In recent years, Bhushan challenged the Master of the Roster system wherein the Chief Justice of India (CJI) has the authority to allocate cases to different judges and benches. In Shanti Bhushan versus Supreme Court of India (2018), Bhushan, as a petitioner, submitted that though the CJI can exercise discretionary powers for the allotment of cases, the same must be exercised in a fair manner. One of the ways to achieve this is to interpret the 'Chief Justice' to mean the 'Collegium' of five judges of the Supreme Court.

Bhushan leaves behind a commendable legacy for future generations.