OFTEN lauded as Indian ingenuity, jugaad is, in reality, simply people finding ways to cope with inefficient systems. This article examines the ‘slip culture’ jugaad, a response of advocates in Kerala's trial courts to trial courts’ inefficient court management practices.

On my first day as an advocate at my firm, I was sent to the district court in Ernakulam to get a case adjourned. Even though this was an easy task, the prospect of appearing before a judge for the first time made me nervous. Clutching the heavy case file, I reached the court hall early and was muttering to myself the two lines I had to say to request the adjournment.

As I stood there, rehearsing in my head, another advocate approached and asked if I would be present in that courtroom for a while. I nodded and said yes. She immediately thrust a neatly cut, square piece of paper into my hand and told me to just say, “For the respondent.”

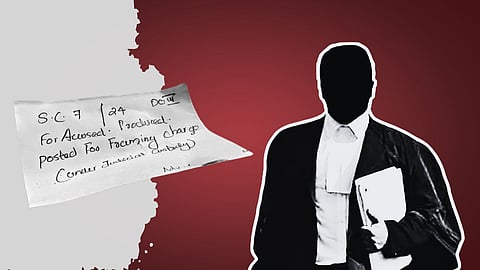

Before I could explain that it was my first day in court and that I did not fully understand what she was saying, she had already rushed out of the court hall. When I took a look at the paper, it had the case number, a brief note about the submission to be made before the court, the name of the court in an abbreviated form, and the name and phone number of an advocate written on it.

I understood that I was supposed to say “For the respondent” when the case was called. Still uncertain about whether I could make a submission on a case I knew nothing about based on the instructions of an advocate I had never met, I decided to ask a nearby lawyer for guidance. She assured me that this was a common practice.

As I started to regularly appear before the trial courts in Ernakulam, Kerala, I came to understand that this was indeed a regular feature of courtroom life. Junior lawyers and clerks often dashed between courtrooms, handling these slips to advocates.

The immediate reason for the prevalence of the slip culture is the trial court’ roll call system. At the start of the day, the court master or Bench clerk in a trial court calls out the list of all the cases listed on a particular day to confirm whether the lawyers are ready for hearings (usually scheduled after the roll call), whether the parties are present, whether various steps or proceedings have been taken in a case, whether the parties are ready for mediation, etc.

Even though only a short submission needs to be made during this time, an advocate needs to be present in the court to do that. Failure to appear can lead to adjournments or, if absences are frequent, dismissal of the case for non-prosecution.

The challenge arises when advocates have multiple cases listed in different trial courts on the same day (a common occurrence). It becomes impossible for an advocate to be present at the roll call in all the courts where their cases are scheduled.

This problem is exacerbated by the fact that the trial courts in Kerala do not have live display boards informing the advocates of the cases being called in real time. Even though video conferencing facilities are available in almost all these trial courts, the courts are still not set up to accommodate advocates appearing via videoconferencing.

Trial courts in Kerala do not have mics for the court staff who are calling out cases in the roll call nor does the court have a display board showing to the lawyer appearing online the case being called out. Thus, there is a high chance that lawyers who appear online may miss the cases being called out in the roll call.

Most trial courts in Kerala follow a specific order of calling cases based on case type. Advocates who frequently appear before these courts often use this order to make an educated guess about when their cases might be taken up. Such guesswork is risky because lawyers can only predict when the particular case type may be called, not the time their case will be taken up.

Moreover, the court's schedule can vary significantly because of fewer cases being listed, more adjournments, or the judge spending additional time on a case, making these guesses even more uncertain.

As a result, advocates and clerks rely on other advocates present in the court to make short submissions based on the slip, to ensure that their cases are represented. Typically, slips are handed out for cases requiring only minimal submissions, such as “The accused is present,” “Steps will be taken,” or “Parties are ready for mediation.”

That said, a judge occasionally poses questions or raises concerns about the case, expecting a response from the advocate present. In such moments, the lawyer with the slip often finds themselves in an awkward situation, hastily explaining that they are merely “proxy counsels”, representing on behalf of the lawyers with the vakalathnama and will relay the court’s concerns to the primary lawyers.

While these occasional embarrassments do occur, the practice persists. Advocates recognise that at some point, they too might need to rely on another lawyer to make submissions on their behalf. This mutual reliance sustains this practice.

While the mutual camaraderie between advocates in this matter is laudable, the legality of this practice is questionable. The Supreme Court, in the case of Sanjay Kumar versus The State of Bihar and Ors. warned an advocate-on-record (AoR) for sending a proxy counsel for a case, observing that “Any ‘arzi’, ‘farzi’, half- baked lawyer under the label of ‘proxy counsel’, a phrase not traceable under the Advocates Act, 1961 or under the Supreme Court Rules, 1966 etc., cannot be allowed to abuse and misuse the process of the court under a false impression that he has a right to waste public time without any authority to appear in the court, either from the litigant or from the AOR, as in the instant case.”

This view was reiterated by the Supreme Court in the case of Surendra Mohan Arora versus HDFC Bank. However, this illegality is forced onto most lawyers due to poor case management practices of the trial courts.

In 2015, the Kerala High Court introduced the Kerala Civil Courts (Case Flow Management) Rules, 2015, based on the Model Case Flow Management Rules, to improve the management of civil cases in trial courts.

These rules provide for a system where the court would prepare two cause lists, Cause List I contains the cases at the stage of appearance of parties and steps, and the other cause list contains all other cases.

The cases in Cause List I are to be dealt with by the court officer, while only the cases listed in Cause List II are to be called on the open court. Cases from Cause List I will be listed in open court only if the parties fail to take the necessary steps. The implementation of these rules could have significantly reduced the chaos of junior advocates and clerks scurrying across courtrooms to find someone to represent their cases.

Unfortunately, this legislation, like most case management legislation in the country, remains largely on paper and has yet to be meaningfully enforced in Kerala’s trial courts.

I would argue that the role envisaged for the court officer in the Kerala Civil Courts (Case Flow Management) Rules, 2015 is limited, and more procedural work could be entrusted to the court officer.

In a 2021 decision, the Kerala High Court directed that the court officers of family courts be entrusted with tasks such as fixing the date of appearance, referring parties to mediation, and calling for a meeting of parties to fix the date of hearing of proceedings in the court.

Even though this decision was made in the context of proceedings in the family court, similar powers can be entrusted to all court officers. Entrusting the court officer with the power to attend cases in the procedural stages is not a silver bullet that will put an end to the slip culture.

However, when combined with improved case management practices, better video conferencing facilities and live display boards, it could help mitigate the reliance on the slip system in Kerala’s trial courts.