“I have successfully privatized world peace.”– Iron Man 2

“… for all these autocrats, dictators, and real-estate agent rulers, they simply want absolutely no bindings…”; “… difference between Putin regarding his aggression in Ukraine and Trump consists in the fact that Putin at least attempts to bring forward juridical, international arguments to justify the attack on Ukraine… The language of International is employed there… Trump makes absolutely no international legal arguments; he acts in his customs specifications as if International Law does not exist at all…” – Anne Peters, Director, Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law.

WITHIN ONE MONTH of President Donald Trump being conferred with the inaugural FIFA Peace Prize, the American Society of International Law (‘ASIL’) on January 5, alleged that the President had violated international law.

In the span of that one month, the United States had unilaterally intervened in Venezuela, and US forces abducted the sitting President Nicolas Maduro.

Much has been written on the illegality of this intervention since then. However, we take this event to make a different epistemic point by interrogating the normative meaning of peace, historiography of US imperialism in Latin America, and examining the USA’s paranoid reading of international law, linking its intervention in Venezuela with a story of Calcutta.

Venezuela, the Security Council Resolution 2803, that gives effect to the Gaza Peace Plan, and several other events surely raise questions about President Trump’s conceptual understanding of ‘peace’. As scholars of Responsibility to Protect, human security, and peace, we too are puzzled by the privatised understanding of peace by FIFA, a football association, that seems to contravene the views of doyens of international law and their scholarly societies.

For the sake of sanity, let us assess the traditional contours of peace. German legal academic Hans Ulrich Scupin states that ‘peace’ is an orderly procedure that upholds the independence of all the sovereign states and condemns the hegemonic nature of an empire-like entity.

The Venezuela fiasco is an appropriate time to analyse our existing structures designed to guarantee the rule of law, and our moral quotient that compels us to imagine a world where justice is the basic fibre that binds it. It is in this context that we assess the belligerent attitude of FIFA’s inaugural peace-prize winner in the context of the history of American foreign policy, and the restrictions imposed by the Constitution of the USA and foreign policy.

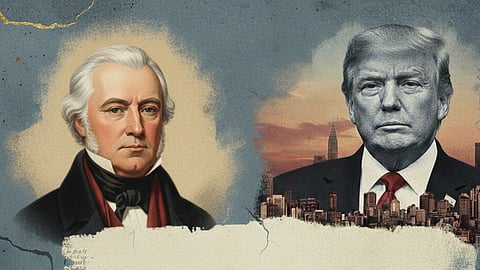

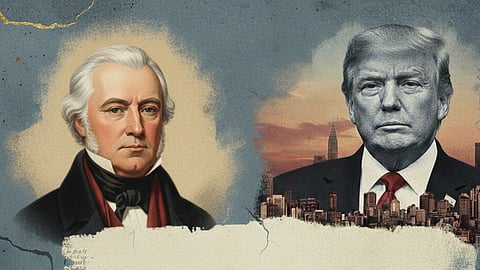

The visions of the Monroe Doctrine

The privatized model of peace and unilateral intervention in Venezuela is a part of a long history of US intervention in Latin America. The policies of former President Ronald Reagan and the International Court of Justice case in Nicaragua v. USA (1986) are familiar introductions to any student of international law. But the story truly begins with the infamous Monroe Doctrine.

Created to counter the hegemony of the Holy Alliance, the policy quickly escalated the cause of USA’s imperialist ambitions. Simon-Bolivar’s heroic efforts had decolonised the South American continent from the Spanish Empire and established the Republic of Gran Colombia, which initially comprised Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela.

As the USA quickly accorded recognition to these newly formed entities, it simultaneously thwarted the Spanish attempt to repossess South America by posing as the defender of the American Continent. The idea, originally based on a proposal by British foreign secretary George Canning, was later used by James K. Polk to justify the annexation of Texas - ultimately leading to the concept of ‘manifest destiny’ of the US.

Over the 19th century, ‘manifest destiny’ - a divinely ordained mission where people of the world would realise that American political institutions were worth emulating, remaking the world in America’s image - became the linchpin of American foreign policy. In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt used it to maneuver an arbitral settlement between Venezuela and Great Britain. The Monroe Doctrine was a particular application of the Grand Strategy scheme - something that seeks to order the world according to vision of a particular state, as the prospective hegemon deploys all its political, economic and military aims to further their interests - something the US continues to follow today.

Carl Schmitt’s prophecies on controlling the meaning of peace and security

The US's contentious imperial legacy is worth discussing in the context of President Trump. “The United States of America is running Venezuela,” said Stephen Miller, the White House Deputy Chief of Staff for Policy, recently, “By definition, we are in charge…for them to do commerce, they need our permission.”

There was something ‘Schimittian’ about Miller’s words. While German legal theorist Carl Schmitt remains notorious for his defense of the Nazi regime, he was also an ardent critic of the liberal tradition of law, premising an alternative model of international law that critiqued the US’s imperialist ambitions. The US, he argued, was operating in the shadows, using the neutral language of liberal law and international legal systems as imperialist devices. Schmitt argued that a hegemon always acted in a Großraum, an ample geopolitical space, strategically created to exercise political homogeneity. For the US, this space was Latin America.

The USA was able to capture the narrative of international law by providing a conceptual alternative to the European balance of power in the form of ‘collective security’. ‘Collective Security’ became an accepted mode of settlement through the League of Nations Covenant and the UN Charter, the documents that relied heavily on American maneuvering.

Schmitt insisted that controlling the meanings of peace, security, and intervention was the key to maintaining hegemony. The institutions and language of the liberal legal model are chimerical enough to create a legal-political bully. The Monroe Doctrine allowed the USA to displace the older form of imperialism with a new international legal form of imperialism, thus allowing it to reserve a greater degree of sovereignty.

How the US plays with international law

The drafters of the Constitution of the USA sought to help a newly emerged and weak country reap the benefits of international law through free trade, secure borders, and a policy of neutrality.

But the idea of American Exceptionalism allowed the USA to self-appoint itself as a providential leader, and the development of international law was bound to be a fascinating journey. International law emerged as a profession due to the efforts of James Brown Scott and George Kirchwey. Their efforts were instrumental in the establishment of the ASIL.

There has not been a dearth of incidents in which the American government has used international law for strategic purposes. Andrew Dickson White was instrumental in cementing the portrayal of Hugo Grotius, a Dutch jurist, as the ‘father of international law’ at the first Hague Peace Conference. Strategically, the American government took up the portrayal of a formidable soft power, believing in Dutch tolerance, admiration for trade and strong Protestant ethics.

The domestic law of the USA has had an interesting relationship with international law, evident through how powers relating to declaration of war, and use of force in international relations, is distributed among Congress and the President. Since declaring a state of war requires a higher threshold of democratic participation, the power came to be divided between the Congress and the President.

Article I of the US Constitution grants Congress the power to declare war, and Article II makes the President the Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy. The drafting history of the Constitution suggested that the President had a limited defensive power under Article II to respond with force in case the nation was attacked. Article I, Section 8, gives Congress explicit powers to declare war, raise and support armies, and maintain a navy, whereas Article II makes the President the Commander-in-Chief. Technically, the authorisation of military action, even for lesser contentious issues such as the use of force, requires the consent of Congress.

However, various US Presidents, such as Reagan and Obama, have used military force without express permission from Congress. President George H.W. Bush used military action to topple Manual Noriega's government in Panama in 1989. American legal scholar John Yoo has argued that the President could resort to such powers within the Commander-in-Chief Clause of Article II.

Another method that has been used are statutory force authorisations, such as the Authorisation for Use of Military Force (‘AUMF’), two laws passed by the US Congress over 2001 and 2002, which authorise the President to use force against nations, organisations, and persons that carried out terrorist activities against the USA.

While AUMF laws are situation-specific, the Trump administration used it to give legality to the assassination of Iranian military commander Qaseem Soleimani in 2020. With increasing pressure within the Congress to repeal the AUMF, the Trump administration found a different document to justify its Venezuela operation - the Authority of the Federal Bureau of Investigation to Override International Law in Extraterritorial Law Enforcement Activities, something that could be seen to violating Article 3 of the ILC Draft on State Responsibility (acts of a State may be wrongful under international law regardless of domestic law’s characterisation), and Article 27 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969 (a state cannot rely on domestic law to justify its failure to comply with a treaty).

Legitimising imperial violence - from Venezuela to Calcutta

In its statement on January 5, the ASIL, while critiquing President Trump’s actions also asserted that Nicolas Maduro “unlawfully claimed power” and “exacted untold brutality and suffering on the people of Venezuela.” A Foucauldian reading of this statement would help us understand the politics of the statement of the ASIL. For Foucault, power forms knowledge and produces discourse, and in this way, ‘truth’ remains situational.

Western academia has justified illegal interventions, bringing ‘illegal but legitimate’ doctrine earlier. Hence, we receive the statement of the ASIL on the domestic politics of Venezuela with a certain degree of incredulity.

Maduro’s characterisation in the ASIL statement is similar to British politician Thomas Macaulay’s description of the last Nawab of Bengal. In his book, The Black Hole of Empire, Indian political scientist Partha Chatterjee notes that Macaulay’s lurid depiction of Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah as “one of the worst specimens” of Oriental despotism - as indolent, debauched and cruel - to justify British conquest and civilizing missions in India, was exemplary of how imperial power deploys historical narratives to legitimise political domination.

Macaulay’s narrative thus participated in a pedagogy of culture that inculcated the belief that non-European polities were inherently incapable of lawful self-governance, while simultaneously sanctioning a pedagogy of violence by legitimating coercive intervention as a necessary response to supposed barbarism.

Chatterjee shows that such narratives become embedded within the discourse of international law, bridging juridical rationales and imperial violence. International law appears universal and civilizing at the center while systematically condoning exceptional violence against those coded as uncivilized in colonial peripheries. The brutal colonisation of India was justified by producing a caricature of rulers as ‘oriental despots’ and then suggesting colonisation as ‘pedagogic’ for the people of India by Macaulay.

The statement of the ASIL does not in any way question the violent pursuit of American imperialism but focuses on one individual- Trump. Recently, author Suchitra Vijayan critiqued this fixation, suggesting that “if he left today, the rotting structures of annihilation would endure- producing successors just as brutal, no matter the party.”

The oppressed and debilitated people suffer from imperial violence everywhere. The privatized model of peace will not bring emancipation. Scholars and peers from the Global North must acknowledge it.