The surge in antimicrobial resistance in India poses a burgeoning threat due to inadequate healthcare infrastructure and lack of awareness. The author necessitates concerted efforts by the Union and state governments to mitigate the public health crisis.

—

ANTIMICROBIAL resistance (AMR) is a complex and multidimensional issue that has emerged as a critical public health issue all over the world.

In India, where health has consistently been relegated to the back-burner of the public policy agenda, this problem has remained unaddressed for long due to the policy and regulatory silence surrounding the issue.

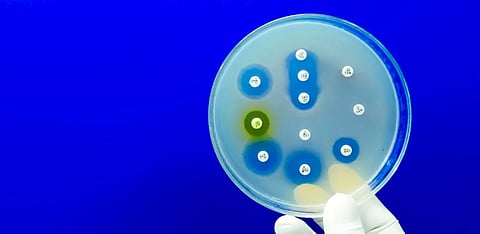

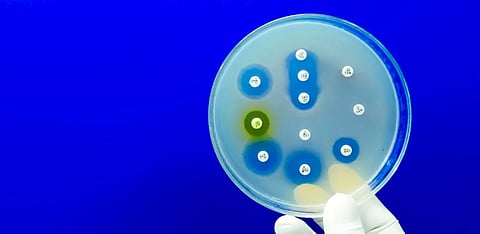

AMR is the ability of microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites) to genetically adapt and become resilient to the treatment effects of medications.

This leads to the emergence and proliferation of drug-resistant pathogens that acquire resistance to the intervention of broad-spectrum antibiotics and subsequently also to third-generation (cephalosporins) antibiotics.

AMR renders the standard treatment protocols ineffective, leading to faster disease spread, incidences of prolonged and severe illness among patients, increased mortality as well as higher costs, thus making healthcare both expensive and intensive.

“Antimicrobial resistance is the ability of micro-organisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites) to genetically adapt and become resilient to the treatment effects of medications.

The mortality data on AMR is extremely concerning. It has been estimated that bacterial AMR was directly responsible for 1.27 million global deaths in 2019 and was a contributory factor in 4.95 million deaths worldwide. The economic implications are also huge.

According to a study by The Lancet, AMR could result in US $1 trillion in additional healthcare costs in the next couple of decades.

Also read: Why is Delhi's air much worse than you think

Although AMR poses a worldwide public health threat, its severity is amplified by poverty and social disparities. The problem worsens due to the lack of effective regulatory oversight on healthcare service providers such as doctors and pharmacies, resulting in over-prescription of drugs and the prevalence of over-the-counter drugs.

The lack of awareness among the public and the consequent higher prevalence of self-prescription further compound the problem.

In low and middle-income countries, various factors have resulted in an unchecked proliferation of AMR, such as insufficient access to clean water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) for both humans and animals; inadequate infection and disease prevention and control practices in households; dismal healthcare facilities; limited availability of quality and affordable vaccines, diagnostics and medications.

There is insufficient awareness and knowledge and inadequate enforcement of pertinent legislation to curb the spread of AMR. Individuals residing in low-resource environments and vulnerable communities are thus particularly affected by the contributory factors contributing to and also the outcomes of antimicrobial resistance.

AMR is a natural process and the consequence of the self-defense mechanism among microbes. Antimicrobial drugs have a selective and differential efficacy on microbes.

Drugs attack and kill vulnerable microbes, but a few strains that are either naturally or intrinsically 'tougher' or have acquired resistance and immunity to particular drugs survive and multiply.

Naturally occurring AMR is a relatively slower process and advancements in biomedicine can counter it to a large extent. However, the occurrence of AMR is exacerbated in speed, scale and intensity because of induced human factors related to healthcare treatment and other allied processes.

“One of the primary factors driving the emergence of AMR lies in the widespread overuse and inappropriate utilisation of antimicrobial medications, particularly antibiotics.

At this stage, it becomes a global public health hazard with a far greater scale and severity.

One of the primary factors driving the emergence of AMR lies in the widespread overuse and inappropriate utilisation of antimicrobial medications, particularly antibiotics.

Also read: Explained: How do Vaccines Work?

Misuse of antibiotics manifests in various scenarios, such as when antibiotics are prescribed unnecessarily for conditions that do not warrant them. For instance, a patient with a common cold caused by a virus might receive antibiotics despite their ineffectiveness against viral illnesses.

Additionally, incomplete courses of antibiotic treatment, where patients stop taking their medication prematurely once they start feeling better, contribute to this problem.

To illustrate, consider a scenario where a doctor prescribes antibiotics to a patient with a mild respiratory infection, even though evidence suggests that most cases of respiratory infections are caused by viruses and do not require antibiotics.

The patient's symptoms may resolve without antibiotics, but the unnecessary prescription still exposes harmless bacteria to the medication, potentially leading to the development of resistance.

Similarly, in agriculture, antibiotics are often used in livestock farming to promote growth and prevent diseases. However, the indiscriminate use of antibiotics in animal husbandry contributes to the spread of resistant bacteria.

For example, if antibiotics are routinely administered to healthy animals as a preventive measure, it creates an environment where resistant bacteria can thrive and spread to humans through consumption of contaminated meat or contact with animal waste.

In both healthcare and agricultural settings, overuse and misuse of antimicrobials create selective pressure on bacteria, favoring the survival of resistant strains.

This phenomenon is akin to evolutionary selection, where bacteria that possess resistance genes are more likely to survive and reproduce, eventually leading to the proliferation of resistant microbes and rendering antibiotics less effective over time.

“Bacteria that possess resistance genes are more likely to survive and reproduce, eventually leading to the proliferation of resistant microbes and rendering antibiotics less effective over time.

Also, suboptimal infection control measures not only facilitate the spread of antimicrobial resistance but also hinder efforts to combat it effectively.

Inadequate practices in preventing and controlling infections within healthcare facilities and communities lead to the proliferation of resistant micro-organisms.

Examples include a lack of emphasis on hygiene, improper sterilisation techniques, and the absence of effective infection control protocols, all of which facilitate the transmission of resistant pathogens.

For instance, in a hospital setting, if healthcare workers do not follow proper hand hygiene protocols, it can result in the spread of resistant bacteria from one patient to another.

Similarly, if medical equipment is not adequately sterilised between uses, it can serve as a reservoir for resistant microbes, leading to healthcare-associated infections that are difficult to treat with standard antibiotics.

Likewise, in communities, poor sanitation practices can contribute to the dissemination of resistant bacteria. For example, in areas where wastewater treatment is inadequate, antimicrobial residues from pharmaceuticals can enter the environment, promoting the development of resistant strains.

Further, the absence of comprehensive surveillance and monitoring systems for antimicrobial resistance presents challenges in detecting and addressing emerging resistance trends.

Without accurate data on the prevalence and incidence of resistant microbes, it becomes difficult to implement targeted interventions and evaluate the effectiveness of control measures.

The lack of new drug development also contributes to the problem of effectively addressing the problem. The pipeline for the development of new antimicrobial drugs, particularly antibiotics, has been consistently shrinking in recent decades.

Pharmaceutical companies face financial disincentives to invest in antimicrobial research and development due to the high costs, low profitability and regulatory challenges associated with bringing new drugs to market.

In addition to these medical factors, social and environmental factors have also contributed to the rapid proliferation of AMR. For example, increased global travel and trade facilitate the spread of resistant micro-organisms across geographic borders.

“Pharmaceutical companies face financial disincentives to invest in antimicrobial research and development due to the high costs, low profitability, and regulatory challenges associated with bringing new drugs to market.

Resistant pathogens can be transmitted between countries through infected individuals, contaminated food and water and in healthcare settings, contributing to the global dissemination of resistance.

Environmental contamination is also a potent source for the persistence and transmission of resistance genes, further exacerbating the problem. Antimicrobial residues and resistant bacteria can also enter the environment through wastewater, agricultural runoff and improper disposal of pharmaceuticals.

Additionally, excessive use of antimicrobial agents in agriculture, particularly in livestock farming, also contributes to the emergence and spread of resistant bacteria. Antibiotics are often used for growth promotion and disease prevention in animals, leading to the development of resistant strains that can be transmitted to humans through food consumption or direct contact with animals.

It is thus evident that owing to the multiplicity of factors that cause or contribute to the development of AMR, addressing the challenge requires a multifaceted approach aimed at eliminating the root causes through improved antimicrobial stewardship, infection prevention and control measures, surveillance and monitoring, research and development of new drugs, and collaboration across sectors and countries.

Recently, there has been a growing realisation of the criticality involved in addressing the immensity of challenges that AMR poses. Policymakers in India, too, have tardily woken up to the burgeoning threat posed by AMR.

India, along with member states of the World Health Organisation (WHO), South-East Asia Region, adopted the Jaipur Declaration on Antimicrobial Resistance in 2011.

Subsequent to the declaration, the National Programme on Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance was launched under the 12th five-year plan (2012–17).

Also read: Caste is in the very air we breathe

In 2017, India developed a National Action Plan on AMR in alignment with WHO's Global Action Plan (GAP) for AMR. The plan is premised upon certain strategic priority objectives.

GAP's objectives aim to improve awareness and understanding of AMR through effective communication, education and training and strengthen knowledge and evidence through surveillance largely modeled on WHO GAP-AMR's Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System.

“Addressing the challenge [of AMR] requires a multifaceted approach aimed at eliminating the root causes through improved antimicrobial stewardship, infection prevention and control measures, surveillance and monitoring, research and development of new drugs, and collaboration across sectors and countries.

Promoting research and development on AMR through national and international collaborations are other areas of intervention.

In pursuance of the GAP, India has instituted regulatory frameworks to monitor the sale and usage of antimicrobial drugs. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and the National Centre for Disease Control, for example, have launched the antibiotic stewardship initiative, which includes publishing treatment guidelines for antimicrobial use in common conditions as well as hospital settings.

Additionally, guidelines have also been issued to promote judicious antibiotic prescribing practices within diverse healthcare settings.

Other agencies have also released protocols and guidelines on their respective domains. The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India has notified the antibiotic residue limits in food from animal origin.

Similarly, the Indian Network for Fisheries and Animals Antimicrobial Resistance has been established with the Food and Agriculture Organisation's assistance. To supplement this, the Central Pollution Control Board too has published the draft standards for antibiotic residues in pharmaceutical industrial effluent and common effluent treatment plants.

While the policy momentum is welcome, challenges remain. Even seven years after the policy implementation and a strategic push to generate awareness, studies have highlighted that many relevant stakeholders such as public health professionals are not fully aware of the consequences of AMR.

The second and very crucial strategic priority to establish a surveillance ecosystem also suffers from a lack of well-equipped laboratories and a narrow catchment for data collection.

Under ICMR's National Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network, data is currently sourced from only 20 state medical college laboratories which is insufficient to properly circumscribe the severity and scale of the problem.

“Even after seven years of policy implementation and a strategic push to generate awareness, studies have highlighted that many relevant stakeholders such as public health professionals are not fully aware of the consequences of AMR.

Moreover, most health establishments in India suffer from infrastructure and logistical challenges such as a lack of optimal diagnostic facilities and a shortage of physicians and microbiologists. The absence of diagnostic reports or their timely availability inhibits evidence-based administration of drugs during the course of treatment.

Another strategic priority that suffers from implementation constraints is infection prevention and control in healthcare, veterinary settings and animal husbandry.

The infection, prevention and control programme should ensure mandatory incorporation for licensing and accreditation across both public and private hospitals, to ensure compliance. This is yet to be done on the scale desired.

Some research has pinpointed inadequate infrastructure, lack of adequately trained personnel, disproportionate workloads and language barriers among staff as the main challenges hindering the successful implementation of infection control programmes.

Research and innovation in new drug development are mentioned in the policy agenda but have not taken off due to several factors such as a lack of returns on investments.

Pharmaceutical companies are disincentivised from developing novel antimicrobial drugs since bacteria can swiftly develop resistance to newly introduced antibiotics which typically have short, pre-determined treatment durations unlike medications used for chronic illnesses.

India has a good number of pharmaceutical firms and academic institutions capable of conducting research and development initiatives on novel classes of antibiotics, provided they receive encouragement and support from the government which has not been very forthcoming thus far.

While the Indian National Action Plan (NAP) is a forward-looking policy endeavour, its implementation is hindered by many of the usual barriers that plague the healthcare ecosystem in India.

Consequently, the pace of implementation has been sluggish. The primary obstacle lies in the absence of dedicated financial allocations. Since health falls within the jurisdiction of state governments, financial constraints often limit their ability to allocate funds for emerging health initiatives amidst competing priorities.

“Pharmaceutical companies are disincentivised from developing novel antimicrobial drugs since bacteria can swiftly develop resistance to newly introduced antibiotics which typically have short, pre-determined treatment durations unlike medications used for chronic illnesses.

Therefore, establishing a separate funding mechanism for AMR, with collaboration between the Union and state governments, is crucial.

Also, to gain better and more comprehensive insights into resistance patterns nationwide, it is imperative to bolster laboratories and gather data from a wider network of both public and private hospitals.

Since trained microbiologists and microbiology laboratories are fundamental to surveillance efforts, enhancing laboratory quality, increasing the presence of trained personnel, ensuring adequate infrastructure, implementing robust quality control measures and offering hands-on training support from tertiary care institutions become extremely important in any AMR containment initiative.

Intersectoral regulatory coordination between the health, environment, veterinary and agriculture sectors is also essential in crafting containment strategies for AMR.

Besides, enhanced implementation strategies with clear timelines, strengthening regulatory enforcement governing the sale, prescription and use of antimicrobial drugs; controlling over-the-counter availability and inappropriate use; and penalties for non-compliance to deter violations shall also go a long way in effectively curbing the menace.

On the promotive side of policy intervention, it is essential to conduct intensive campaigns to raise awareness. These campaigns should encompass mass media initiatives and specialised programmes tailored to educate both healthcare professionals and the general public.

Strategies for fostering behavioral and attitudinal changes need to be formulated and executed effectively. These efforts are crucial for triggering a shift in perspectives and practices surrounding antimicrobial use and resistance.

Finally, measures such as training and capacity-building initiatives, promoting antimicrobial stewardship practices, expanding surveillance networks, interoperability and data sharing between surveillance systems, community engagement, awareness and sensitisation of various stakeholders shall also serve as effective mitigation strategies.

“Since health falls within the jurisdiction of state governments, financial constraints often limit their ability to allocate funds for emerging health initiatives amidst competing priorities.

It is important to remember that formulating policies and action plans is only the first step. Unless effectively channelised through ground-level implementation, they shall only provide lip service to the problems they seek to remedy.

AMR has been an overlooked issue in the health policy discourse. Unless urgent containment measures are taken with a commensurate political and executive will, it will overwhelm the health delivery ecosystem already bursting at the seams.