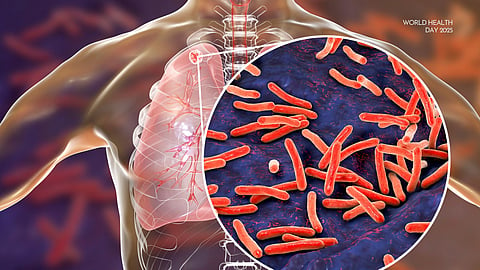

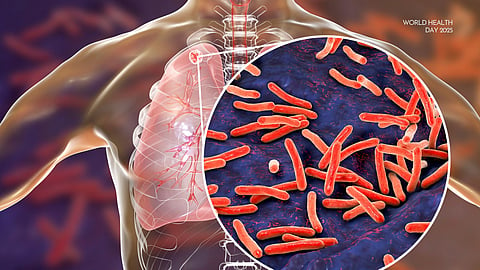

TUBERCULOSIS (‘TB’) HAS BEEN AROUND FOR A LONG TIME. Anyone with basic knowledge about the disease will tell you that we have found traces of the bacteria and the deformities it causes in human remains dating back thousands of years. This has led to the infamous claim that TB is the oldest disease known to humankind. By the time Robert Koch “discovered” the Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 1882, TB had gone by many names — phthisis, consumption, the white plague, scrofula, the King’s Evil. It had also claimed countless lives as a leading cause of human death throughout history, killing over 1 billion people just since Koch identified the bacteria. The stigma surrounding TB started early as well. Hippocrates warned his students against treating people with TB because nearly all of them would die, and this would harm the students’ reputations.

How is it, then, that this ancient disease still kills millions of people, more than HIV and malaria combined each year, making it the world’s deadliest infectious agent? The answer is complicated, involving how the disease spreads, the bacteria’s unique physiology, and the socio-economic disparities that drive the epidemic.

But in some ways, it’s a simple narrative of poverty and neglect. This story is reflected in graphs showing the precipitous decline of TB mortality in the United States as living conditions and occupational health and safety standards improved well before we discovered streptomycin* or widely administered the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (‘BCG’) vaccine (see figure 1 below). Today, we have better tools to detect, prevent, and treat TB and a deeper understanding of its socio-economic determinants. Yet we are still struggling — some would say failing — to eradicate the disease because of years of global neglect and failed approaches.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), approximately 10.8 million people fell ill, and 1.25 million people died from TB in 2023, the most recent year for which complete data is available. At almost 11 million, the total number of new cases reflects a slight increase from the year before and a broader trend of rising global TB incidence since the COVID-19 pandemic started in 2020. Thirty so-called “high TB burden” countries accounted for 87 percent of the total TB cases in 2023, with five countries constituting 56 percent of the worldwide total — India (26 percent), Indonesia (10 percent), China and the Philippines (6.8 percent each) and Pakistan (6.3 percent). Alarmingly, 25 percent of the people who fell ill with TB in 2023 were not registered by their national TB programs, meaning many, if not most, of them went undiagnosed or untreated. This global gap, sometimes called the “missing millions,” reflects the persistent challenges in finding, diagnosing, and treating people with the disease.

This piece examines two crucial challenges to eliminating TB: chronically insufficient funding and lack of innovation and the persistence of a problematic treatment model — directly observed therapy (‘DOT’).

The innovation and funding gap

Despite a few recent advances, the global TB response has been hobbled by insufficient funding and a lack of innovation for decades. The Trump administration’s recent dismantling of USAID and seemingly indefinite freeze on U.S. foreign aid have worsened these challenges. A December 2024 report from Treatment Action Group and the Stop TB Partnership found that annual funding for TB research and development (‘R&D’) reached only 24 percent of the $5 billion target countries had set at the United Nations High-Level Meeting (‘UNHLM’) on TB in September 2023. Notably, especially now in light of the decisions in Washington, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (‘NIH’) was the top individual investor, contributing 34 percent of the total funds. The Gates Foundation was the second largest donor, contributing 19 percent of all TB R&D funding in 2023. With philanthropies accounted for 24 percent of all funding, the report warned that we may be “entering a dysfunctional Gilded Age dynamic in which lavish spending by billionaires and tax-exempt charitable endowments sets an innovation agenda that should be owned by and accountable to the public.” In fact, India and South Africa were the only two countries to achieve their “fair share” of the 2023 spending targets, defined as allocating at least 0.15 percent of overall R&D expenditures to TB.

Taking a step back, until recently, we experienced a 50-year period during which no new drugs were developed to treat TB. Compare this to HIV and COVID-19. The first cases that started the global HIV epidemic were identified in the early 1980s. About 40 years later, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved more than 50 medicines to treat HIV. We moved even quicker during the COVID-19 pandemic, developing multiple vaccines and treatments at breakneck speed and administering over 13 billion vaccine doses worldwide in just a few years. Yet, in over 60 years, only three new drugs — bedaquiline, delamanid, and pretomanid — have been approved to treat TB, one of the oldest and deadliest diseases known to humankind.

What is the reason for the dearth of funding for innovation in the fight against TB?

It essentially comes down to the lack of profitable markets for new TB technologies in wealthy countries and, thus, the lack of financial incentives among the major pharmaceutical companies. Compare the size and projected growth of TB therapeutics to weight loss drugs. In 2023, the size of the global TB market was about $2.1 billion, and it is projected to grow to about $3 billion by 2030. That same year, the global market for anti-obesity medications was $6 billion, but it is projected to grow more than 16 times to $100 billion by 2030. Underlying these numbers is the fact that almost 90 percent of people suffering from TB are in low- or middle-income countries.** Even in wealthy countries that are home to the drug producers that drive the global R&D agenda, people affected by TB are generally members of marginalised groups, including prisoners, people experiencing homelessness, migrants, and others.

The United States has been the main international donor for TB for many years, contributing about 50 percent of all donor funding. Since President Trump ordered the aid freeze on January 20, TB drugs have vanished from clinic shelves, TB testing has ground to a halt, and the collection of critical data needed to guide the disease response has stopped around the world. As a senior USAID official wrote last month, the U.S. foreign aid freeze “will lead to increased death and disability, accelerate global disease spread, contribute to destabilizing fragile regions, and heightened security risks - directly endangering American national security, economic stability, and public health.” Within 20 minutes of sharing his memo with staff by email, the official was put on administrative leave.

The Trump administration is also severely cutting the budget of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (‘NIH’), “by far the world’s biggest funder of biomedical research.” The consequences for basic science, clinical, and public health research will likely be devastating. The U.S. administration also seems poised to terminate all NIH grants in South Africa in fulfillment of a presidential executive order threatening to stop all U.S. aid to the country due to purported discrimination against Afrikaners — white South Africans of Dutch descent. According to Treatment Action Group (‘TAG’), between 2019 and 2023, NIH grants to South African research institutions totaled about $118 million for TB research, including trials for new treatments for TB meningitis and drug-resistant TB in children and a TB vaccine for people living with HIV. TAG also notes that NIH investments in South African TB research are matched by domestic funding and that “[e]very major TB treatment and vaccine advance in the past two decades has relied on research carried out in South Africa.” To this point, the most recently FDA-approved TB drug, pretomanid, is named after the South African capital, Pretoria, where a non-profit coalition developed the drug, and four of the six ongoing TB vaccine trials currently in Phase III involve patients in South Africa.

Directly observed therapy (DOT)

Directly observed therapy, or DOT, is a prominent example of the lack of innovation in the global TB response and an avatar of our distrust of people affected by TB. A 2021 editorial calling for person-centered TB care in place of DOT declared: “The politics of TB care is replete with paternalism and the prizing of tradition, hampering innovation, flexibility and the establishment of respect and trust between providers and people with TB.”

Recently, I wrote about the dogma of DOT with colleagues, including three TB survivors. We examined DOT’s history, evidence, and impact from a human rights perspective. As others have, we concluded that DOT’s global dominance as the primary TB treatment model is incompatible with a rights-based disease response. Instead, the way forward is to focus on differentiated people-centered care and community empowerment for a participatory response.

The idea of DOT is simple. In 1999, as part of a global marketing campaign for the treatment model, WHO defined DOT as “watching patients taking their medications”. In practice, this has generally required people to visit the clinic daily, often for months, to receive and be observed taking their medicines. As you can imagine, this sort of “facility-based” DOT is profoundly disruptive and costly for people with TB, interrupting their lives and livelihoods, all because we do not trust them to take their medicines. More recently, WHO described DOT as “any person observing the patient taking medications in real-time,” noting that the person “does not need to be a health-care worker” and that DOT can “be achieved with real-time video … and video recording.”

Nonetheless, DOT has also been aptly described as “[s]upervised swallowing,” a patients’ “leash,” “[w]asteful, inefficient, and gratuitously annoying,” “alienating and authoritarian,” and for “‘poor people’ only.”

DOT’s history and origin are contested. The early TB studies and later public health emergencies most often associated with DOT’s development and success either didn’t actually use the treatment method or were likely successful for other reasons. For example, the Madras Study conducted in modern-day Chennai in the late 1950s heralded the end of the age of sanatoriums for TB and laid the foundation for DOT. However, the patients receiving care outside the sanatorium in the study did not receive DOT. They mostly self-administered their treatment with periodic home visits from health workers and robust treatment support, including nutritional supplements, financial aid, and assistance from dedicated social workers. New York City’s TB program credited DOT as the key to its success in stemming the rise of DR-TB in the city in the 1990s. However, the city’s response to the outbreak comprised other critical components, such as a 400 percent staff increase to 600+ people, a tenfold budget increase to over $40 million, and an aggressive community outreach program targeting the most vulnerable groups. As with the Madras Study, robust programmatic resources and outreach appear to have been at least as vital to the city’s success as “watching patients taking their medications.”

Astonishingly, there is no conclusive proof that DOT is more effective than self-administered treatment. Yet, a growing body of evidence delineates its harm to people with TB. Four of the most recent systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials comparing DOT to self-administered TB treatment produce essentially the same result: DOT is no more effective than self-administered treatment. In its 2017 TB treatment guidelines, WHO sums it up, stating, "overall, the evidence [is] inconsistent in showing clear advantages of DOT alone over [self-administered treatment] or vice versa.”

Making matters worse, studies show that people with TB incur significant expenditures undergoing DOT and that DOT is also associated with stigma, discrimination, and privacy breaches. The financial burden, stigma, discrimination, and lack of privacy, in turn, deter health-seeking behavior and erect barriers to treatment adherence and completion, leading to worse individual health outcomes and the further spread of TB.

For decades, our myopic focus on DOT has also precluded scientific progress in the development of alternative treatment models or the adaptation of existing models used for other diseases, such as HIV. When responsibly employed, the recent proliferation of “digital adherence technologies” for TB (DATs) may be viewed as a positive, if qualified, innovation trend. Yet, DATs alone do not represent a genuinely new treatment paradigm, as they exist in DOT's broader, disempowering context. DATs also introduce novel risks. They produce vast amounts of sensitive digital data on people affected by TB and present feasibility and inclusivity challenges for marginalised populations who lack access to the required hardware or electronic infrastructure.

Despite its contested history, inconclusive supporting evidence, and growing list of harms and risks, WHO doubled down on DOT in its most recent TB treatment guidelines. The guidelines recommend a new, shorter treatment regimen, the first significant improvement in the treatment of drug-susceptible TB in decades. However, they recommend “daily dosing … ideally under direct observation” for the new four-month treatment.

Even more astonishingly, the guidelines falsely conflate DOT with a broader set of interventions under the umbrella term “treatment support.” The guidelines define “treatment support” as people-centered care designed around “individual patient’s needs, acceptability and preferences.” The definition then incorrectly states that “[h]istorically, this group of interventions were [sic] labelled as ‘directly observed treatment’ or DOT.” This is patently false and directly at odds with WHO’s previous, more accurate definitions of DOT mentioned above. This false conflation appears to be an effort to distance the institution from the “legacy terminology” of DOT with all its baggage without doing the work to replace DOT in practice.

As we face persistent global health crises in a shifting funding paradigm, we must renew our commitment to ending TB. Defeating the oldest disease known to humankind is only possible if we increase the resources we dedicate to innovation. It also requires us to do the hard work of discarding old approaches that cause more harm than good and replacing them with a community-driven, people-centered disease response.

Notes: *Streptomycin is the first antibiotic discovered to treat TB. The BCG vaccine is currently the only vaccine for TB but is generally only effective against TB in children.

**As noted above, the World Health Organization reports that thirty low- and middle-income countries accounted for 87 percent of all new TB cases in 2023.