With the impact of the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic on our education system, the time has come for schools to take a centre stage in safeguarding the future of our children, and for our governments to continue working on evidence-based, inclusive and resilient methods of imparting learning to our students, writes PIYUSH NARANG.

————

IN February 2020, right before COVID-19 struck in India, I held a mathematics class in an upper primary grade at an all-girls government school in Delhi. There were 75 students in the class that day, most of whom were first-generation learners. The attendance in this class of 78 students hardly fell below 90%, a number much higher than the national average of 72%.

Cut to September 2020 – six months into the pandemic, our online classes would have around 32 of these 78 students present on a good day. The other 60% had not only lost their access to an uninterrupted education and nutritious food, but were also more exposed to the likelihood of being subjected to child labour, domestic violence and exploitation. The impact of the pandemic was truly unimaginable.

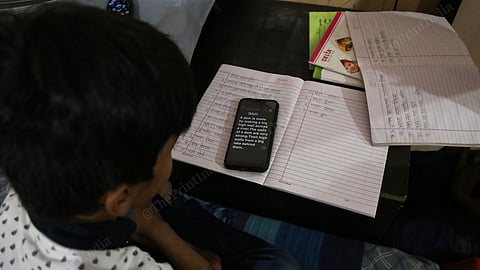

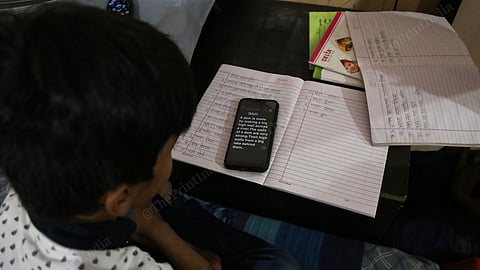

Within months of the school shutdown, there was an essential yet ambitious overhaul to an alternate learning system – a digital learning system. However, this transition has not been completely possible for the majority of our 250 million students who lie on the "other side" of digital divide.

A UNICEF report on remote learning reachability states that only 24% of Indian households have reliable internet to access online education. This digital divide is exasperated by access to electricity, and smartphones.

For families with two children and limited financial resources, it has been difficult to engage both children meaningfully in online classes. The access to learning has not only come down due to socio-economic dependencies such as internet penetration, digital literacy, electricity and smartphone ownership, but also based on gender, with families tending to give access to limited digital resources to male children over female ones.

For once, it seemed like COVID-19 had halted India's education system. However, as this generational catastrophe in education started hitting the country in its face, the governments, both at the centre and state-levels, adapted faster than ever to mitigate this learning disruption.

In May 2020, the Union Ministry of Education, launched an array of digital education initiatives under the Pradhan Mantri eVidya Programme to facilitate multi-mode access to learning and teaching. A one-stop digital platform for access to e-learning content (in 18+ languages) called DIKSHA, a website and a toll-free helpline to support mental well-being called Manodarpan, a group of 34 DTH channels with the goal of "one class, one channel" called Swayam Prabha, amongst many other initiatives under the eVidya Programme, anchored the delivery of education centrally.

With time, there was a realization that there is no "one size fits all" solution to this problem of digital divide and access to education. States and local governments thus started launching contextual and customised solutions to ensure learning for all children. What followed was a wildfire of innovative initiatives that used a myriad of mediums to reach children effectively.

Under one such initiative titled "Padhai Tuhar Dwar" launched by the Chhattisgarh government, different districts have been conducting mohalla classes (community classes), also called loudspeaker classes, for students from far-flung forests. "Padhai Tuhar Dwar" also gave birth to a program called "Bultu Ke Bol", under which teachers in Chhattisgarh used the Bluetooth facility to transfer more than 60,000 audio lectures to around 27,000 parents, ensuring access to learning for students without smartphones and internet connectivity.

In Madhya Pradesh, channels under the All India Radio have been broadcasting class-wise and subject-wise educational programs from Monday to Saturday (11 am to 12 pm). This initiative, called "Radio School", brought visually challenged students under the ambit of digital education. States/Union Territories (UT) like Jharkhand, Kashmir, and Arunachal Pradesh have also extensively used radio as a medium to impart education. Nagaland distributed learning content to students through pen drives and DVDs at a nominal cost.

State governments have had to use both old media (radio, television, Bluetooth, loudspeakers) and new media (WhatsApp, YouTube, online classrooms) to ensure continuity of education for as many children as possible.

Within a week of the lockdown back in March 2020, the Himachal Pradesh government started planning for digital education assuming a long-term school closure. With "Har Ghar Pathshala", Himachal Pradesh became one of the first states to launch a digital education program. Using WhatsApp as a medium, more than 80% of the students in the state have been receiving high quality academic content from 10:00 am – 12:00 pm during the weekdays.

Similarly, the state of Rajasthan created over 20,000 WhatsApp groups to connect teachers and students to share digital learning content. This model has been replicated abundantly in different states and UTs.

In July 2021, Kerala Education Department's YouTube channel "KITE Victors" hit 3 million subscribers. Interestingly, Kerala has been using the revenue generated (approximately INR 126 lakh since its inception) by advertisements on this YouTube channel to improve the quality of the content uploaded on the channel.

As states contextualised their way of education delivery, what remained a perpetual challenge were assessments and monitoring of learning outcomes. To this end, Haryana, under its initiative "Ghar Se Padho Abhiyaan", developed an app called "AVSAR" to conduct monthly assessments for students from classes 1 to 8.

Unfortunately, even with such policies in place, effective digital education has been a distant dream for a countless number of our students. The pandemic has undone decades of progress made under the Right of Children to Free & Compulsory Education Act of 2009, the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, the Beti Bachao Beti Padhao, the Midday Meal Scheme and other such measures.

For a year and a half now, our children have not only been losing out on learning outcomes in their current classes but are also "forgetting" their learnings from previous classes. Anecdotal evidence by both parents and students have strongly indicated the desire for schools to be reopened. This is backed by recent surveys among Indian parents.

As these debates of school reopening become rife, we need to pause and reflect on our learning from this disruption and think of what our students would need in the future – a more equitable and resilient education system.

Crisis often creates an opportunity for a bigger change. Now is the time to reimagine a post-pandemic education and capitalise on the newfound inclination to evolve faster than ever.

The reopening of schools in the country will bring many challenges, it will however also enable a long-term shift towards a more accessible system with opportunities such as:

There are many lessons to be learnt from the impact COVID-19 pandemic has had on our education system. Schools take a centre stage when it comes to safeguarding the future of our children, and as schools re-open, radical inclusion in teaching should be the new normal. Governments will have to continue working on more evidence-based, inclusive and resilient methods of imparting learning alongside Covid-19.

The time to re-imagine a post pandemic education system is now.

(Piyush Narang is an engineer-turned-educator, currently working with Young Leaders for Active Citizenship (YLAC) at the intersection of civic education, policy, and advocacy. The views expressed are personal.)