As India seems to have lost its Constitutional values in a 'kumbh ka mela', will the search for them end in their rediscovery or will they be replaced by counterfeit values? What does Hindi cinema, the synecdoche of India, have to offer as an ending to this story? This review of Pathaan mulls over the question.

——

THE trajectory of the discourse of Hindi cinema has been a good indicator of the pulse of the country. Post-Independence Hindi cinema and the moniker 'Bollywood' are completely different things though. Bollywood came to represent an industry that used film as a medium to paint aspirational vistas as the country liberalised from the early 1990s onwards. Cinema became incidental, a mere by product of this advertisement of the future.

This was then a time for the rise of a new breed of directors and producers like Aditya Chopra and Karan Johar. Unlike their fathers, they brought on the bling with exotic locations and dazzling costumes, but never ventured beyond the settled norms of patriarchy and orthodoxy, except through some exceptions when it came to interfaith relationships.

There was a near-total obliteration of a pluralistic cultural ethos based on the Nehruvian values of social welfare and secularism, a good example of which was the elder Chopra's film Dharmputra (1961). A classic song from his earlier Dhool ka Phool (1959) goes: "Tu Hindu Banega Na Musalman Banega, Insaan Ki Aulaad Hai, Insaan Banega" in the simple yet profound words of Sahir Ludhianvi. The 1990s were, in short, the beginning of the end of a conscious, relevant cinema that had once been popular and mainstream.

It was also a period that saw the stupendous rise of Shah Rukh Khan, a.k.a. SRK.

Things unravel and how. Fast forward to Pathaan.

In its Bollywood mould, the film is already a success. It is typically reinforcing all the stereotypes and clichés of this machine geared towards profit.

“At its best, Pathaan is a reactionary film making a mockery of the espionage genre, and at its worst, a schizophrenic movie. It uses the clichéd trope of jingoism of which Pakistan is the byword, yet it must now reclaim the self and the citizen in a belligerent landscape of Hindu nationalism.

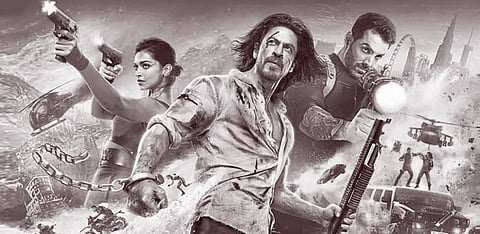

It is also patently bad cinema. Neither SRK, with his chiselled charisma, nor the dusky and leggy Deepika Padukone, do anything beyond being eye candy. For all the sexy song-and-dance, there is zero chemistry between the two. And for all its action and locations, the film barely commands the energy and oomph of the Bond film that it has so apparently — and so poorly — copied. The worst of it is the background music. The Yash Raj Films (YRF) spy universe, to which this film is the latest addition, is comically ambitious, but it knows where the bucks lie, and it knows how to get them.

So, why should Pathaan matter?

It matters because what would have been just a big Bollywood film is now another site of conflict that is directly proportional to an ideology rooted in hate and fear. As SRK returns to the screen after a hiatus, his family and he have been in the news with his eldest son sadly becoming a target not too long ago. Other actors and directors have suffered as well, but this is hardly in isolation. It is all but part of a larger culture war that will keep unfolding as narratives are increasingly hardened.

Expectedly, Bollywood has become a good sitting duck. So, Pathaan at its best is a reactionary film making a mockery of the espionage genre, and at its worst, a schizophrenic movie. It uses the clichéd trope of jingoism of which Pakistan is the byword, yet it must now reclaim the self and the citizen in a belligerent landscape of Hindu nationalism. Total anarchy, embodied in the character of John Abraham, provides a counternarrative. Passing references are made to the way the defence personnel in the service of India are treated. Kashmir and the watering down of Article 370 of the Constitution provide the 'just' cause for Pakistan to act up.

Pathaan can wear all the nationalism he can muster on his sleeve, but today he is no longer the cardboard, loyal character in the service of the nation.

It is not as simplistic as it may seem because today even the mere mention of these events is not tolerated. To be truly nationalistic today would mean to be amnesiac. Therefore the most mundane, if not entirely innocent, referral to facts is to tread dangerous territory.

SRK, the Muslim outside and within, has the nom de plume 'Pathaan' given to him affectionately by an endearing Afghan villager. Hackneyed as it may seem, these are no longer casual events but an existential to-be-or-not-to-be. In the film, he is an orphan, another giveaway in a time when identity is defined in strict and singular terms. The state of being an orphan, a perennial source of drama in Hindi cinema, is now a state of refuge for an identity that cannot be revealed, whose very mention might put you in mortal danger.

The other Khan, the 'bhai' who makes a cameo appearance in the film, has been more shielded from the bigotry of the times, but he too is cautious.

There can be little sympathy for Yash Raj Films, which is more than guilty of reinforcing stereotypes that tend towards orthodoxy and ostentation in equal measure. Following in the footsteps of the films of the studio which are guilty of being part of the bandwagon that has created the discourses which have poisoned public life in India, Pathaan is, therefore, hardly inconvenient. But now every little word must be weighed before it is spoken, no matter how trite the phrases — 'Don't ask what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country'.

Pathaan can wear all the nationalism he can muster on his sleeve, but today he is no longer the cardboard, loyal character in the service of the nation. Even the bravado the two Khans pull off as they sit and reminisce towards the end saying their time is not yet up sounds pitiably lame yet somehow sad.

SRK is now a Khan first. The time is past when he was 'Raj Malhotra' or 'Aman', the NRI from Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jaayenge and Kal Ho Na Ho respectively, in a foreign land but undeniably Indian.