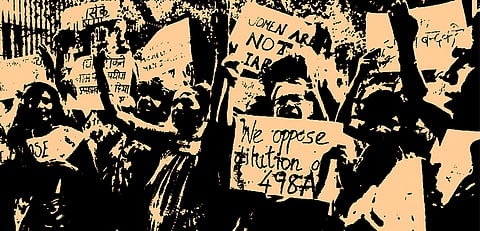

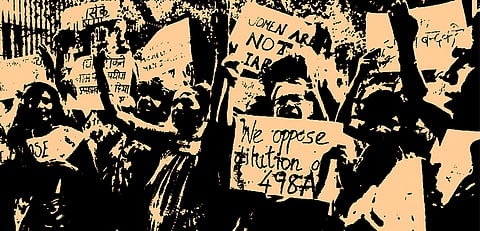

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he State's presumption of the likelihood of harassment of husbands at the hands of their wives, is an argument which is raised quite often against any gender-specific law, especially in crimes such as cruelty, dowry, domestic violence, sexual harassment, rape, and others. This argument is put forth almost in all disputes between a husband and a wife and sometimes it is also used by the legislature to even recognise and criminalise certain acts which severely harm the mental and physical health of a woman, such as marital rape. This misuse argument can largely be said to have stemmed from the allegations of misuse by wives with respect to the law of cruelty under Section 498-A of the IPC.

In a series of cases pertaining to cruelty under Section 498-A, it is the judiciary which has given strength to this argument a number of times, including in the judgment of the Supreme Court in the Rajesh Sharma v. Union of India on July, 2017 and has continued to accept it even in the most recent case which was reviewing Rajesh Sharma in Social Action Forum for Manav Adhikar v. Union of India judgment of which was delivered on in September, 2018.

In the Rajesh Sharma case, the Court had gone a step further in legitimising this argument by laying down guidelines to prevent misuse of law of cruelty against women in which it had directed the setting up of welfare committees, consisting of paralegals, social workers, volunteers and other suitable persons to scrutinise a complaint by a woman before the police even take cognisance of it and to give its opinion to the police. Further, it held that till the report of this committee was received, there will be no arrest. In effect and contrary to the objective of setting up of the committee, this judgment gave enough time for the accused husband to abscond, put a halt on the functions of the police to investigate further or make an arrest until the committee report in that case comes out and delay the process of justice and relief for the woman.

In the subsequent Manav Adhikar case, the court rightfully accepted that the social welfare committees have no role to play during investigation and prescribing duties to the social welfare committees will tantamount to judiciary overreaching its power as it is the Parliament who makes the law. However, the Court has only done a half-baked job in correcting its error in its previous judgment. The Court has in fact further underlined its anxiety that "the abuse of the penal provision [referring to Section 498-A IPC] has vertically risen:" and has gone on to suggest that "it is obligatory on the part of the legislature to bring in protective adjective law and the duty of the constitutional courts to perceive and scrutinize the protective measure so that the social menace is curbed".

The repercussions of the above judgment is significant in the ongoing struggles of women facing violence in their marital homes. The apprehension and anxiousness of misuse in the mind of legislators, judges, government officials only lead to a situation where they evaluate any case without a full consideration or examination which it otherwise rightfully deserves. The consequences of this apprehension leads to severe obstruction to access to justice to women and preserves a never ending cycle of abuse and violation of their rights.

The origin of the misuse argument is from cases which have been labelled as "false" at the time of closure of the case and also too much reliance upon the data of the National Crime Record Bureau to come to the conclusion that since the conviction rate is low, most of the cases registered under Section 498-A IPC are false [see Rajesh Sharma v. State of Uttar Pradesh, (2017) SCC OnLine SC 821, paragraph 7]. This, however, is in no way substantiated on the ground level as well as by concrete data to indicate how frequently the provision is being misused. In fact, women facing violence use this provision to leverage a space for negotiating an end to violence within the space of her husband and marital family [see Anjali Dave, et al, "In search of Justice and care: How women survivors of violence navigate the Indian criminal justice system", Journal of Gender-based Violence (2017), (Vol. 1, 79-97)]. However, the intermediary processes involved right from filing an FIR to pursuing the case in the judicial system often lead such women to turn into hostile witnesses where she retracts her case due to compromise or settlement. These cases in turn are closed as "false" cases and the purpose behind the provision is lost.

Women do not wish to prosecute because of the insensitive treatment of the family, police, hospital staff, and the judiciary and are met with preconceived notions and bias towards saving the family structure and honour, rather than advocating for her safety and well-being. They rather approach the judiciary after failure of several negotiations within the family structure. The cost of approaching the judiciary up to the closure of the case often leads to giving up of residence, financial support and mental well-being. Through these socio-legal "processes of compromise", the woman complainant is presented as a "hostile witness" and this then becomes embedded in public discourse evidencing that women are generating "false" cases to misuse the law, projecting the woman survivor as the one at fault.

Hence, the judiciary is equally responsible for disseminating this argument which reflects a patriarchal mind-set and an existing bias against women. In this regard, with no available data on misuse on cruelty the allegations or concerns of misuse should not be entertained. Any law can be misused, but if riders are put to curtail the misuse, the person for which the law is intended and the goals it sets to achieve will be deterred. A presumption of harassment of the husband cannot legitimise the right of the wife to seek justice from the criminal justice system for flagrant violations against her body and mind.