If the Chinese calendar contained a "year of the underdog", then it is very likely that 1983 would be that year. Not only did this year bring about the most memorable sporting victory for India, it was the ultimate underdog triumph. A victory that would remain etched in collective consciousness of a nation. A victory that would not only transform the game of cricket but have significant impact on the Indian economy in the years and decade to come. A victory that would play a crucial transformational role for India and Indians many years into the future.

On the morning of Saturday, June 25, 1983, Amitabh Bachchan was still the reigning superstar of Indian cinema. The most talked about Gandhi was Indira not Rahul. 11 rupees would fetch you one dollar. Donald Trump was still a real estate developer. Octopussy — the James Bond movie, shot extensively in India and featuring a handsome Kabir Bedi in a two-bit role — had just released a few days prior to the final, featuring an ageing, over-the-hill Roger Moore (who should have swapped places with Bedi in the movie!). And India was still in the grips of the "Hindu Growth Rate".

It was on this morning that the third cricket World Cup final featuring the then invincible West Indies was to be held at the iconic Lord's Cricket Ground in London. The West Indies had won the two previous versions against tougher teams (against Australia in 1975 and England in 1979). The team that they were slated to play in their third consecutive final was nowhere near the level of their opponents in the past finals. Frighteningly, the Windies team of 1983 was even better than the ones of 1975 and 1979. This match ought to have been featured in English thesaurus, to illustrate a "lop-sided contest".

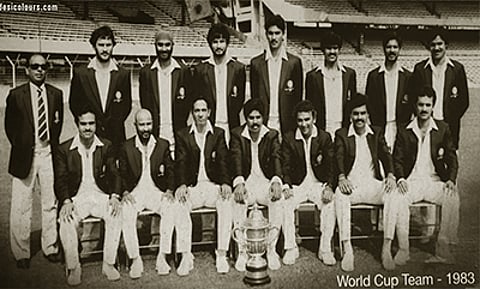

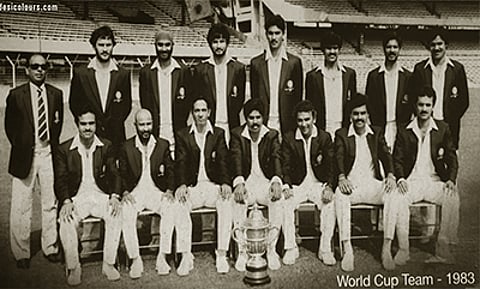

The Windies team that played the 1983 final comprised the best collection of four fast bowlers to ever play for the same team at the same time. To put the strength of the West Indian pace bowling in perspective — not one team in world cricket today has even one fast bowler of the calibre of Malcolm Marshall, Michael Holding, Joel Garner and Andy Roberts, the fearsome pace quartet. On the strength of this bowling attack alone, cricketing logic demanded that the world cup be handed over to the West Indies even before the first ball was bowled.

Now include in this mix, batsmen of the superlative quality of Sir Vivian Richards, Gordon Greenidge, Dessie Haynes and Clive Lloyd. This wasn't even David versus Goliath contest. This was an emaciated David versus steroid-boosted Goliath contest. Mike Tyson versus Mithun Chakraborty (remember Mithunda's seedy film Boxer also released the next year).

Now compare Marshall, Holding, Garner and Roberts with Madan Lal, Roger Binny, Balwinder Sandhu and Mohinder Amarnath — our "pace" attack, if one is permitted to liberally construe the word "pace". A bunch of dibbly-dobbly bowlers against the best pace quartet in the 150-year history of international cricket. More like Ferrari versus Hamara Bajaj scooter. Or, a super-computer versus the Remington typewriter.

If you were to bet a pound on India winning the 1983 World Cup, you would get 66 pounds in the event India won. 66-1 odds.

The best batsman of the Indian team (Dilip Vengsarkar) had already, literally, lost his nose and his place in the final, to a vicious bouncer from Marshall — best of the West Indian pack — early on in the tournament. Marshall, nonchalantly picked out Vengsarkar's fragments of bone and skin from the ball, in the same way you would pick strands of grass stuck to the ball's seam, and continued bowling as if nothing had happened.

Except for Kapil Dev, not a single Indian team member from that XI was good enough to be the 12th man — let alone demand a place in the playing XI of the West Indies.

Yet India won. And how.

I was barely six and half years old on that day. It is my earliest memory of anything. I distinctly remember the crowd that had gathered in our house to watch the final (on our black and white Weston TV). Friends, family and relatives. I recollect, watching with trepidation and anxiety, our "puny" Indians play against the "giant West Indians". How could we ever beat these giants – the thought plaguing my mind all through the match.

I remember the ruckus when the 9th Windies wicket fell (at 126, chasing 183, Andy Roberts LBW to Kapil Dev) — our home erupted in joy. It was now clear that the target of 184 was beyond reach through the last wicket added 14 more stubborn runs. Finally, Amarnath's dismissal of Holding triggered celebrations that I haven't yet forgotten. It was pure, unalloyed joy. A nation exhaled. We were world champions for the first time. And cricket would ascend to become India's unofficial religion.

The growth trajectory of cricket in India post 1983 is well documented. But the 1983 victory was much more than a mere win in a cricket one day international. Its impact transcended the cricket field. It instilled confidence and hope. It spawned a generation of Indians who were unafraid to dream, who dared to dream, who were ready to take on the world with confidence. After all, we had just won the World Cup. That too in the land of our erstwhile colonial masters.