OF the little-known works of Lord Thomas Babington McCaulay are his literary works. In Lays of Ancient Rome, Horatius asks an important question, “And how can man die better/ Than facing fearful odds, /For the ashes of his fathers, /And the temples of his gods?”

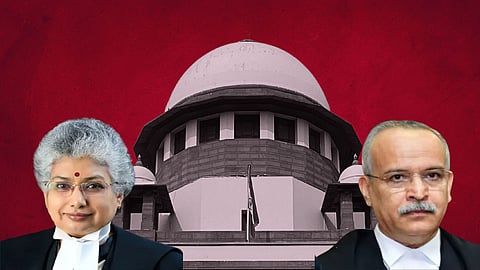

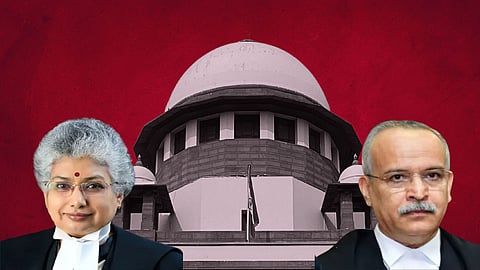

The Supreme Court was faced with a similar question, when a Christian pastor, Ramesh Baghel challenged the judgement of the High Court of Chhattisgarh which had ordered him to bury his father in a distant village after some Hindu residents of Chhindwada where he lived, opposed the burial in the communal graveyard which was not just in the same village but also in their own private property. The case was heard by two judges of the Supreme Court (BV Nagarathana and Satish Chandra Sharma, JJ), and ended in a split verdict. Notably, the affidavit of the State which has been quoted extensively by Justice Nagarathana avers that, “Any person who has forsworn the tradition of the community or has converted into a Christian is not allowed to be buried at the village graveyard…According to the villagers, a Christian person cannot be buried in their village be it at the village graveyard or the instant Petitioner’s own private land”. The answer to this lis would not just be intuitive by allowing a man to be buried where other Christians have also been buried, a fact buttressed by affidavits of other Christian tribals whose families are buried there were also placed before the Court, including the Appellant’s own aunt and grandfather as the Court notes. Yet, that was not to be.

Justice Nagarathana correctly delivered a severe indictment of the village authorities, including the State and called it a betrayal of the principles of secularism. She also notes that this led to the ostracization of the Family in the village and set aside the High Court order. Justice Satish Chandra Sharma, however, upheld the High Court order. The Judge, in my view, commits a grave constitutional error in his judgement by allowing the restriction of ‘public order’ in Article 25 to defeat the substantive right of freedom of religion and conscience itself.

Indeed, while the State ought to limit religious traditions, that may potentially lead to a defeat of public order, can the state use the public order defense to curtail a fundamental right through arguments of alarm? This public order bogeyman has been used to defend a wide variety of otherwise impermissible actions of the state such as bans on internet, banning of media channels, banning of books, preventing religious conversions under the garb of laws which are almost ironically titled ‘Freedom Of Religion Acts’. Notably, the judgement of Justice Sharma fails to even lay down, with the requisite judicial rigor, the scope, framework and contents of events that could disrupt public order. Nor does the judgement go into whether the concerns were well founded.

Indeed, the demarcation of Christians within the tribal community who have been renegaded to a graveyard 25 kilometers away is a standalone tangible form of discrimination. The Court has, in my opinion, ignored the Constitutional question staring at it in the face of structural biases and religious discrimination. The framers of the Constitution were cognizant of various communities having different religions, distinct languages, and diverse cultures. It is axiomatic that the whole edifice of our Constitution is based on inclusion and tolerance. The correct reading of the dispute ought not to have seen this graveyard as a religious one but one where people residing in the same village were thrown out of the graveyard merely because they practiced a different faith.

Casteism, and religious discrimination in public wells, schools, higher educational institutions and now even in death, must be combatted head on, and be defenestrated. While I agree that an expeditious and dignified burial ought to have been given to the deceased, it is indeed a matter of concern that the larger constitutional question on discrimination was not referred to a bench of three judges. What the judges agreed on, however, is that the body of the deceased should be buried 20 kilometers away under police protection. What is missing from the final verdict, however, is the direction of to the State to demarcate burial grounds for Christians, perhaps because the second judge did not get on board with it.

In a diverse country like ours, this case threw up a challenge to foundational ideals of equality and non-discrimination. Indeed, this reminds one of Donne’s sonnets, ‘Death Be Not Proud’ where he says to death, ‘Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men’. Desperate men who, in this case, riled up a supposed threat to public order deprived Baghel’s father of dignity in his final surcease while the Court looked on as a hapless observer unable to provide relief.