THE IVORY towers of Powai’s Hiranandani Gardens, an upmarket township full with resplendent bungalows, penthouses and condominiums, cast long shadows over the 90 feet road outside the Evita Building.

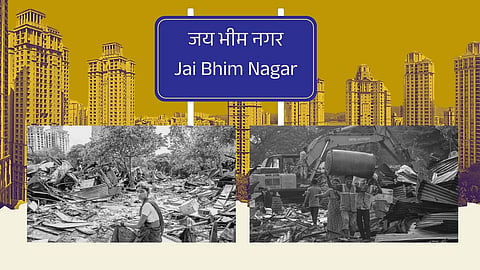

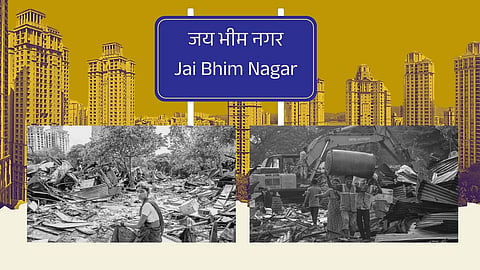

The footpath has sheltered over three thousand people since June 6, 2024, when the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (‘BMC’) and the Mumbai police bulldozed the homes of 650 families of Jai Bhim Nagar basti.

Amidst the blue tarpaulin tents, a resilient social movement has emerged through the collective action of Mumbai's student-youth, civil rights activists, and Jai Bhim Nagar residents. For the past ten months, they have demonstrated in front of the BMC office and Galleria Mall, among other places, held public meetings at Sabki Library, and even launched a children’s newsletter ‘Sabka Ghar, Sabki Pehchaan’. Everyone’s home, everyone’s identity.

“We are just like mosquitoes here,” said Savita, a resident of Jai Bhim Nagar, to an activist of the Jai Bhim Bachao Samiti, a student youth civil rights group, “There's no bathroom, no water. It has been fifteen days since anyone has gone to a proper toilet. What is the point of living in the filth? We are not even allowed to take a shower. What is the point of living for thirty years? We had our documents, but [after the demolition] we don’t know where they are now. They’re saying ‘Show us the documents’. Where will we get the documents from anymore?”

Jai Bhim Nagar is far from the only working-class neighbourhood in Mumbai to face such a ruthless eviction.

In February 2024, a thousand residents were evicted without notice from Govandi’s Panchsheel Nagar basti. The demolitions were carried out brutally and in haste, leaving them no time to collect their belongings or documents. The people have since refused to leave the area, asserting their right over the land that, for many, has been their home for over twenty years. Makeshift pandals have been set up at the entrance of the colony as a defence against any further demolition.

Maisha, an organiser from the Jan Haq Sangharsh Samiti, an organisation for the advocacy of workers in affairs of the city and state, told the Leaflet that people soon started occupying the space, “Where earlier people used to loiter outside the homes, activities started happening. At the basti entrance we started doing movie screenings, performances, and meetings.”

There is a stark contrast between the high-rise complexes of Mumbai’s elite and the homes of the construction workers who built them, the domestic workers who maintain them, and the street vendors who feed them.

This contradiction demands an answer from India's courts and judicial machinery. As private capital bulldozes through the ‘City of Dreams’, do its people still retain their inalienable Right to Housing?

Adarsh Priyadarshini, a member of the Jai Bhim Nagar Bachao Samiti alleged that at the time of demolition, BMC and the Mumbai police had treated the basti residents in a brutal manner. “They served a letter to Hiranandani that ‘now this is your land, and you are entitled to protect the land’. From that day onward, Hiranandani encircled the whole land and put up a board that trespassers will be prosecuted,” he said.

Hiranandani Group was contracted in 1987 to construct affordable housing under the Powai Area Development Scheme. Today, that land is a luxury township of Greco-Roman condominiums, ostentatious penthouses, and sprawling swimming pools. Jai Bhim Nagar started as a labour camp, as the home to migrant construction workers from Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh, employed by a then-nascent Hiranandani Group.

How did such a radical shift occur?

The land in question has had disputed ownership since 1968. In 2007, the Supreme Court definitively denied ownership of the land to Lake View Developers (a Hiranandani subsidiary). However, a few weeks later, a ‘mysterious fire’ ravaged the basti, burning 150 homes. Lake View Developers was granted approval to rebuild “temporary worker housing.”

This administrative decision opened the gateway to Hiranandani Gardens. The Group now had an unprecedented level of control over the workers’ lives. The builder could not only price-control their access to electricity, water, and gas connections; but also obstruct their access to documents (electricity bills, ration card, and proof of permanent address), thereby suppressing their legal recognition. The collusion between the municipality and the developer set the stage for ensuing legal challenges.

In 2017, the first eviction notice was issued under Section 52 of the Maharashtra Regional and Town Planning Act (‘MRTP Act’), prompting three civil suits contesting the eviction. Despite the pending cases, a second notice was served on June 3, 2024.

Three days later, the basti was completely encircled by police forces. Peaceful protestors, human chains, and photos of Babasaheb Ambedkar were met with lathi charges, beatings, and stompings. The ‘encroachers’ who had constructed Hiranandani’s luxury apartments and the ‘illegals’ who cleaned and maintained the houses of the ivory-tower aristocrats were dragged to the footpath, where they could only watch as their homes were demolished.

The demolition of Jai Bhim Nagar reveals the precarious status of the Right to Housing in India.

The Constitution of India lacks an explicit encoding of the Right to Housing, unlike other modern Constitutions like those of South Africa (Section 26), Kenya (Article 43(1)(b)), and Brazil (Articles 182 and 183).

Speaking at a report launch by Jai Bhim Nagar Bachao Samiti in February 2025, advocate and constitutional law scholar Gautam Bhatia explained, “The Courts have been the organs which have effectively interpreted the Constitution to introduce something akin to Right to Housing.”

Bhatia was referring to the Supreme Court of India’s ruling in Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation (1985), which deliberated the rights of pavement dwellers in Bombay against unannounced eviction. The Court drew an explicit constitutional connection between the right to life, the right to livelihood, and the right to shelter.

The judgement, authored by former Justice D.Y. Chandrachud notes:

“The sweep of the right to life conferred by Article 21 is wide and far reaching. An equally important facet of that right is the right to livelihood because, no person can live without the means of living, that is, the means of livelihood…The cost of public sector housing is beyond [migrant workers’] modest means and the less we refer to the deals of private builders the better for all; excluding none. To lose the pavement or the slum is to lose the job. The conclusion, therefore in terms of the constitutional phraseology, is that the eviction of the petitioners will lead to deprivation of their livelihood and consequently to the deprivation of life.”

Olga Tellis was laudable for its recognition of workers’ economic contribution to the city and its deliberations on the constitutional mandate that property must subserve common good. However, its true legacy is one of profound contradiction: the Court offered minimal material relief to the petitioners, and did not order rehabilitation mechanisms.

“The problem is that in the very same judgment, the Court actually allowed for the eviction of these pavement dwellers,” Bhatia told the gathering, “While Olga Tellis was high on rhetoric of Right to Livelihood and Right to Shelter, when it came to actually laying down the law it was a very conservative judgment.”

Olga Tellis created a duplicitous ambiguity which affected subsequent decisions.

On occasions, some courts have emphasised Olga Tellis’ acknowledgement “that poverty itself could constitute a barrier to fundamental rights.” For instance, in Ajay Maken v. Union of India (2019), a case concerning the demolition of Delhi’s Shakur Basti, the Delhi High Court laid down substantive obligations protecting slum dwellers from forced and arbitrary evictions. It held that no authority can carry out a demolition without consulting the inhabitants, conducting a survey, and providing adequate rehabilitation. It further denounced the narrative that frames slum dwellers as “illegal occupants,” recognising that it is the workers’ labour which services the entire city. The verdict ensured that the basti residents were not summarily evicted.

On the other hand, Olga Tellis’ ultimate ruling that “no person has the right to encroach on.. place(s) earmarked for public purpose” has spawned a strain of regressive judgements.

“In these cases, you see derogatory references to people as encroachers who are squatting on public land, and therefore are essentially ‘rightless,’” remarked Bhatia. In Almitra Patel v. Union of India (2000), for instance, the Supreme Court unleashed unadulterated revulsion against slum-dwellers under the guise of cleanliness. Justice B.N. Kirpal doubled-down on the derogatory language of ‘trespassers’ and ‘illegals,’ essentially denying evicted residents of their right to rehabilitation. At one point, the judgement notes, “rewarding an encroacher on public land with free alternate sites is like giving a reward to a pickpocket.”

Bhatia explained, at the gathering, that the inherent ambiguity and “two-faced nature” of Olga Teliis has resulted in a lack of clarity regarding what precisely are the rights available with the people, and under what circumstances, and following which conditions, the State could demolish.

This is not merely a legal ambiguity, but a license for unchecked executive impunity by the police and municipal bodies.

“They served a notice which did not have any official stamp on it,” Maisha recalled to the Leaflet, “The people of the basti went to the SRA office and asked why this notice was served. They started submitting their documents to show that they belong here. The next day, the notice was printed on a big banner and put up, again without any signature. Two months later, they came for demolitions.”

The eviction of two hundred working-class families from Govandi’s Panchsheel Nagar basti had been riddled with gross procedural violations. When the residents protested against a demolition without proper notice, the police responded with a lathi-charge and unlawfully detained seven local leaders.

The Maharashtra Slum Areas (Improvement, Clearance and Redevelopment) Act, 1971 (‘MSA’) mandates that a Slum Rehabilitation Authority (‘SRA’) must survey, plan, implement, and achieve rehabilitation of evicted slum-dwellers. The Court has also emphasised that evictions can only be conducted subject to the condition of relocating protected occupiers under Section 3Z of the MSA.

In Almitra Patel, Bhatia explained, the Supreme Court had noted that regardless of the question of illegal title, before the State evicts anyone, it must adhere to certain procedural and substantive obligations - the government must undertake a survey to verify if inhabitants are eligible for existing resettlement and rehabilitation schemes, and if the State proposes a resettlement package it must meaningfully consult with the residents and demonstrate that it has taken their input in crafting a rehabilitation plan. Further, it has to be a dignified rehabilitation package.

But the bulldozer is a law in itself; demolishing the State’s procedure, the Court’s justice, the people’s lives in its rampage.

“Despite residents submitting their documents in October 2023, the BMC did not follow the procedure of checking documents, producing annexure 2 of eligible and ineligible residents, and so hearings to settle objections and claims,” notes a press note released by Jan Haq Sangharsh Samiti, “The officers were acting as judge and jury, checking the documents on the spot, evaluating their validity and breaking houses.”

On February 8, 2024, residents of Panchsheel Nagar had staged a protest outside the BMC office against the gross procedural violations by the officers. They claimed that the demolition was illegal since no legally valid notice was served, no survey was conducted, and rehabilitation was arbitrarily denied.

“The language of the officers is so wrong,” Maisha told the Leaflet, “The officials say, “You are getting a home also, why should you get housing? You are staying for free. You don’t pay property tax. What right do you have for housing?””

The Court’s failure to acknowledge the injustice of these demolitions, check the powers of the executive, and commit to redress originates from its failure to name the real problem of Builder Raj: the State-Corporate nexus.

Rampant procedural violations by the police and executive bodies makes it seem like basti demolitions are caused by arbitrary violence. But Builder Raj has never been an arbitrary exercise. The cloak of ‘economic development’ hides the true objective of the gentrifying bulldozer: the accumulation and expansion of private capital.