IN THE DELICATE SCENARIO OF DEMOCRACY, literature bears witness but also wields a sword. If one is an observer of Indian politics, the Jammu & Kashmir Home Department's announcement in August 2025 of a ban on 25 books that it classified as "seditious" was hardly shocking. It felt less spontaneous than a psychological act of governance: a panicked retreat into a shroud of national integrity. Yet the more we peered inside this literary purge, we understood that it was not just the ink the state feared on the page but the imagination, the inquiry, the unforgetting histories it mobilised.

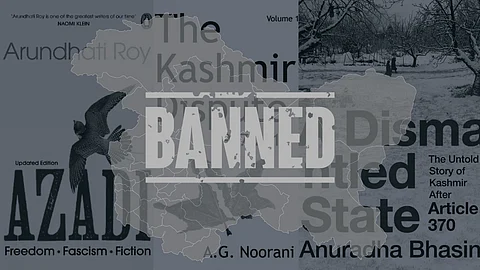

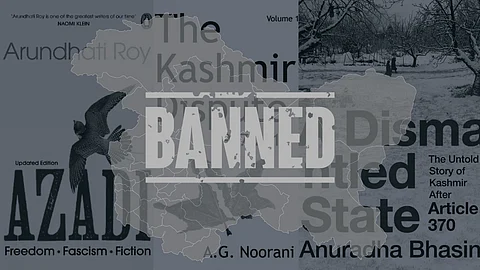

Many of the most respected names in Indian and global scholarship on this banned list are Arundhati Roy, A.G. Noorani, Sumantra Bose, and Victoria Schofield. These works are not incendiary pamphlets or flights of fancy calling for insurrection; they are scholarly texts, journalistic investigations, and political essays chronicling the long, tortuous, and too often tragic tale of Kashmir's contemporary political identity. The overarching authority's decision to ban their circulation and reader access was garbed in the usual threats to sovereignty and assertions that they promote terrorism. Yet, just the faintest breath of scrutiny reveals how predictable and uniform such proclamations are, and crumbles them effortlessly.

The legal rationale was provided under the new Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023, which replaces the colonial Indian Penal Code (IPC). Among several offences invoked are Section 152 of BNS (forfeiture of publication with seditious matter) and Section 197 of BNS (promoting enmity between different groups). Some of these statutory instruments, which are merely brand new forms of old statutory systems based on colonial logic, have been used to imprison revolutionaries under British rule, when the same colonial understanding was a tool of the state's power to repress. What is remarkable about this situation is that a state that is supposedly post-colonial is borrowing from colonial frameworks to police intellect and academic thought, repressing dissenting voices and constructing understandings of loyalty in its shallow terms. This raises an important question: Is it possible for a republic to flourish if it is afraid of its writers?

The political precariousness evident in this decision does not come from nowhere. Since the stripping of Article 370 in 2019, Kashmir has been relentlessly undergoing a campaign of narrative consolidation. Kashmir had once become a polyphony, full of voices (local leaders, poets, historians, international observers), has now been reduced to a monologue - all organized from the control room in Delhi where the script is singular, and any deviation is now "anti-national," a term so often used that it has lost meaning altogether, its threat baritone is now an empty trumpet. In this one-note narrative environment, the banned books didn't get banned because they caused violence, but because they transpired the state-managed illusion of ideological unity. They reminded readers that there is more than one story, more than one pain, more than one way to be patriotic.

For example, Arundhati Roy's Azadi is a meditation on freedom - its ironies and contradictions and on how it has changed in the postcolonial Indian context. Her essays disassemble the machinery of nationalism, a critique that demonstrates how easily the language of liberation can be shaped into the discourse of repression. Noorani's volumes of work are very legalistic and archival, presenting facts which would otherwise not be presented in popular histories. Both Bose and Schofield provide nuanced historical accounts, providing critical global viewpoints that cannot be subsumed by nationalistic propaganda. Banning works like this does not negate misrepresentation; it, in fact, instead fearfully erases difficult truths.

The government's language in its public notice is telling. The books were said to promote "false narratives" and could "mislead youth". The subtle suggestion is that Indian youth are not capable of critical inquiry—that they are "empty vessels" instead of minds with the aptitude to consider arguments and counter-arguments. This paternalism is anti-democratic, suggesting that exposure to intellectual ideas is dangerous, that questions are threats, and that dissent is disloyalty. But such a frame cannot persist in a real democracy. If a state needs to protect its citizens from books, perhaps it is not the books that are dangerous, but the delicate foundations of the state.

In India, book banning is not legally uncommon. Over the years, governments of various parties have banned books ranging from Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses to the writings of Periyar, and even Ambedkar's annotations to Hindu texts. Article 19(1)(a) signals an inherent right to free speech and expression in the Indian Constitution, but also immediately allows for reasonable restrictions under Article 19(2) on various grounds, including sovereignty and public order, decency, morality, and incitement of offence. The obscurity of what constitutes "reasonable" restrictions has allowed a succession of governments to utilize the clauses as a means for political purposes. The latest prohibitions in spirit will reference sovereignty as a government that is less weak, and more likely to prohibit what constitutes an ideological challenge to its practice as a government.

Today, the ideological project of the ruling party in India is based not just on electoral hegemony, but also on epistemic sovereignty and the ability to control what knowledge counts, what is worthy of being remembered, and what ought to be excluded from public discourse. In this context, the book ban is not simply an isolated event, but a part of an entire architecture of silence, like the arrest of journalists, the control of syllabi in universities, the manipulation of the press, the policing of social media users, etc. Everything converges on a stronghold of thought that allows for only the approved history, while the other is heresy.

However, repression of ideas is a paradoxical exercise. The more tightly a state represses ideas, the more those ideas slip out of its grasp. In our digital and disseminated age, a state may ban physical copies of books, but that is like trying to cage a shadow. PDFs are flying around in encrypted networks, scanned pages are going viral, and underground reading groups are thriving. Each act of censorship plants a seed of resistance in those minds. Each banned book becomes an open invitation, a forbidden fruit that is too ripe to ignore.

When a state engages in book censorship, it also lends legitimacy to the contents of those books. In banning literature, it short-circuits the author and promotes them to a martyr of thought, imposing legitimacy on the text as an important truth that has been repressed. The state (perhaps too, in its broader defense of Enlightenment values) does not understand this alchemy; its fear and violence only turn ink into fire. If the purpose was to suppress access, the outcome has done everything but that: curiosity multiples, and hunger for other stories intensifies.

Censorship is also an acknowledgment of defeat – A government that resorts to coercion and confiscation acknowledges its inability to win a battle of ideas through debate, dialogue, and reason, and thus has succumbed to force. A government unwilling to deal with critical questions questions its legitimacy. The secured do not silence; only the insecure are driven to amputate parts of the public discourse to control it. The face of that political insecurity is framed as a national interest. But just beneath that mask is something much more profound, a fear that if people are exposed to the cacophony of voices present in their histories, they may re-acquire the painful ability to pose inconvenient questions.

In Jammu & Kashmir, where the legacies of Partition, insurgency and militarization still haunt the shadows of the valleys, where truth occupies an unstable ground, where every narrative is a battle; every memory, a minefield, to recognize past pain; to humanize the other side is not to celebrate terrorism, so to reclaim empathy from the ends of the terror induced binaries of the state, and the multi-faceted reality of both their and our histories. The banned texts do just that; they aim to reinstate the complicated narrative that has been decimated to oversimplified slogan-based versions of our past. And accordingly, they will pay the price.

This episode also exemplifies the erosion of institutional independence. In a properly functioning democracy, it is the judiciary that holds the executive accountable. The Supreme Court's constitutional benches have continually reaffirmed the sanctity of free expression. In Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras (1950), the Court opined that freedom of expression is the "cornerstone" of democratic governance. In S. Rangarajan v. P. Jagjivan Ram (1989), the Court observed that freedom of expression can only be suppressed when the situation becomes dangerous to the community and threatens public order in a similar manner to a spark igniting a powder keg. In this context, however, it does not seem as if the judiciary does not feels as if it can mount much opposition. The silence of the institutions is deafening, just like the government's claims.

Perhaps the most tragic irony is the government’s fear of its citizens. The ban is not aimed at foreign foes or hostile spies, it is aimed at Indian readers. The state does not trust them with thought. It does not believe that its people can know the difference between fact and fiction, reason or rhetoric. It presumes a kind of intellectual helplessness, a populace too dumb to do anything but read the filtered truths of state-sanctioned textbooks. But the Indian citizen is not so easily fooled. The history of India is the history of ideas in revolution, in reform, in resilience. This nation was born in the pages of Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj, Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste, and Tagore’s Nationalism. To fear books now is to fear the very soul of India.

At the end of the day, a government that bans books communicates more than it suppresses. It communicates its fear, its ignorance, its fear of critics. It tells the world it is unable to be scrutinized, that it prefers to be erased to talk. Ideas are persistent. They will outlive governments. They learn to fly in silence. And in the absence of legitimacy, they continue to talk.

For Kashmir, for India, and the conscience of democracy, we should ask: what kind of nation do we become when we are frightened of our writers?