In the aftermath of the tragic Rana Plaza collapse, efforts have been made to improve safety and workers' rights in the ready-made garment industry in Bangladesh. However, families of the victims and survivors of the collapse are not satisfied with these efforts and want better conditions in the industry so that workers don't have to face such tragedies ever again.

—

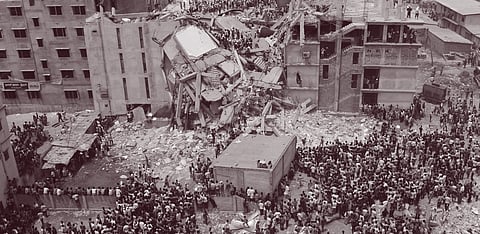

TEN years ago on April 24, 2013, the world witnessed one of the worst industrial disasters in history when the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh collapsed, killing more than 1,100 people and injuring 2,500 others.

The tragedy sent shockwaves around the globe and sparked concerns about the unsafe working conditions in Bangladesh's booming ready-made garment (RMG) industry.

The eight-storey building housed several factories that produced clothing for global brands such as Primark, Mango and Benetton, among several others.

The building's collapse was a stark reminder of the human cost of fast fashion and brought to light the terrible working conditions endured by many of the country's garment workers.

According to survivors, local managers had pressured workers to enter the building and report to work even after deep cracks had appeared in the walls of the eight-storey Rana Plaza building the day before. Engineers had also declared the building unsafe.

Sohel Rana, the owner of Rana Plaza, was incarcerated and is currently facing trial in multiple legal cases following the incident. However, he secured bail from a high court in Bangladesh in the case earlier this month.

The US $28 billion RMG industry of Bangladesh is responsible for 80 percent of the country's annual exports. More than 300 retailer clients from Europe, America, New Zealand, Australia, Japan and Russia, among others, source RMG products from Bangladesh. International brands such as Marks & Spencer, WalMart, Tesco, Zara, Adidas, JCPenny, IKEA, H&M and Uniqlo have set up liaison, procurement and sourcing offices in Dhaka.

Also read: Laws, flaws and accountability

Even though ten years have passed, the survivors and families affected by the Rana Plaza tragedy still carry painful memories and wounds of their immeasurable loss.

Sumi Akhter (26) was a swing operator who worked at the New Wave Style garment factory in Rana Plaza. She started working there at the beginning of April 2013.

Although she survived the collapse of the building, her mother, who also worked there, did not. Sumi was trapped under the concrete rubble for three days before firefighters rescued her. Her right leg was badly injured and had to be amputated by doctors to save the rest of her body. The circulation in her leg had stopped, and it was rotting.

She has to use a prosthetic leg to walk these days.

"On the day of the collapse, in the morning when everyone had entered the building for work, suddenly everything started falling apart. My coworkers were shouting, urging everyone to run. I tried to run and escape, but somehow, I fell down and lost consciousness. When I regained consciousness, I found myself trapped under concrete debris. There were two dead bodies on top of my legs and a concrete beam resting on them," she shared.

Following the incident, Sumi has been unable to find employment, and she needs to replace her prosthetic leg every one-and-a-half to two years. Although she received free prosthetic legs in the first few years after the accident, she had to borrow 90,000 taka (US $846) to purchase her most recent one.

"Sometimes I feel like it would have been better if I had just died there. I don't have enough money to afford new prosthetic legs for walking. Also, I am uncertain about my son's future," she lamented.

Rubi Akhter (55) lost her daughter Morjina, who used to work at the New Wave Bottom Apparels Ltd factory on the fourth floor of Rana Plaza.

"After hearing the news of the building collapse, I screamed out loud and immediately rushed to the spot. I found my daughter's distorted dead body after 17 days of the collapse," Rubi shared.

"I'm living alone now and I miss my daughter so much. Thinking about her always makes me cry. If she were still alive, I wouldn't be struggling so much."

Most of the survivors of the Rana Plaza collapse are currently living in poverty. Their severe physical injuries also make it challenging for them to find jobs.

"Some survivors [are now] begging for a living. Our primary demand is for all survivors to receive compensation for their lost lifetime income, amounting to 48 lakh taka (US $45,660) each." said Mahmudul Hasan Hridoy, President of the Rana Plaza Survivors Association of Bangladesh.

To compensate the people impacted by the tragedy, The Rana Plaza Donors Trust Fund was created through a collaboration among the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the government of Bangladesh, workers' and employers' organisations, and international clothing brands, which had raised US $30 million by 2015. The money was mainly used to compensate victims and their families and provide medical services to the injured.

Since the tragic incident in Bangladesh, there has been a significant shift in the approach toward worker safety in the country's RMG industry. The Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh was established in 2013 as a legally binding agreement between global brands, trade unions, and non-governmental organisations to inspect and remediate factories for fire, electrical and structural safety. The accord has made remarkable progress, inspecting over 1,600 factories and helping to remediate safety violations in many of them.

The Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, a consortium of North American brands and retailers who didn't sign the accord, also took similar steps to ensure the safety of workers in garment factories in Bangladesh.

Their efforts led to the closure of unsafe factories, the renovation of others, and improvement of working conditions for millions of workers. These initiatives have addressed issues such as electricity and fire safety, infrastructure risks, workers' health, freedom of workers association, and the overall working environment.

Both the accord and alliance have completed their operations after working for seven and five years respectively. Now, Nirapon, a non-profit organisation, has taken over the alliance's operations, whereas the RMG Sustainability Council (RSC) has taken over the accord's operations. The RSC now operates as a safety monitoring body in the RMG sector in Bangladesh. However, there are concerns about the effectiveness of RSC compared to the accord as the safety monitoring body of the RMG sector.

Workers' rights issues remain unaddressed

Although there have been significant improvements in the RMG industry, many issues on the worker's end still remain unresolved.

Before the Rana Plaza collapse in 2013, garment workers in Bangladesh used to receive a minimum wage of 3,000 taka per month (approximately US $28 based on the current dollar rate). This amount was later increased to 5,300 taka (US $50) in November 2013, and 8,000 taka (about US $76) in 2018.

"My monthly salary is 10 thousand taka (US $95). And if I do overtime, the amount goes to around 13,000–14,000 taka (US $123–133). It is really tough to go a whole month with this amount. My daughter and I can't even afford our own room to live in. The cost of everyday items has gone up and it is actually tough to meet all the basic necessities with this salary," tells Rozina Begum (25), a junior swing operator working at a garment factory.

Many workers often work overtime to earn additional income to support their families. This can have negative consequences on their health due to the long hours worked. Rozina shared that her usual shift at work starts at 8 a.m. and is supposed to end at 5 p.m., but on some days, they work overtime, which can result in shifts ending between 7 p.m. and 10 p.m. The workers work for up to 14 hours, depending on the amount of overtime.

Forming trade unions to protect workers' rights has become a bit easier since the tragedy, but some obstacles still exist. Although workers are technically free to form trade unions, many are hesitant to do so due to various threats, such as intimidation from employers and the fear of losing their jobs. The process of registering new trade unions is challenging, and rejections of new union registration are also common.

Amirul Haque Amin, President of the National Garments Workers Federation, said, "The Department of Labour [which registers] new trade unions, has problems in [its] practices when it comes to registering new trade unions. A lot of obstacles come from the powerful owners' side as well."

When asked about worker's compensation for workplace injuries, he said, "They don't get [deserving] compensation and treatment facilities. But a pilot for Employment Injury Scheme (EIS) has been launched with the help of the German and [Dutch] governments. Among the [over] 300 foreign retailer clients that source ready-made garments from Bangladesh, nine companies have stepped forward for voluntary financial contributions to the EIS."

The EIS is a social protection program that provides compensation for medical treatment and rehabilitation services, as well as income loss resulting from occupational injuries or diseases. The Bangladeshi Ministry of Labour and Employment launched this scheme in collaboration with the ILO, which will cover the 4 million garment workers in Bangladesh.

Due to initiatives of unions of buyers (such as the aforementioned accord and alliance), the Bangladeshi government and the RSC, safety measures have been taken to make garment factories safer for workers. Safety inspection activities conducted by the accord and the alliance played a significant role in implementing safety improvements in garment factories.

Bigger manufacturers hire subcontractor factories for specific stages of production, such as cutting or sewing. However, these subcontractor factories are not part of the safety inspection programmes because the inspections were only done on factories registered with Bangladeshi trade organisations, the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA), and the Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association, which the subcontractor factories are not.

These subcontractor factories reportedly often operate independently, and may lack the resources and oversight of larger factories, leading to lower safety standards and potential labour violations.

Faruque Hassan, President of the BGMEA, claimed, "We have conducted thorough audits of the fire, electrical and structural safety of every garment factory and have adopted a zero-tolerance policy towards safety lapses. A massive transition occurred after the Rana Plaza tragedy. We have closed down many factories that were deemed unsafe. We also started to strictly monitor the subcontractor factories. We have instructed our member factories to only hire subcontractors that comply with safety regulations and take approval from the retailer client before hiring.

"We have taken the Rana Plaza accident as a lesson and [are] working very strictly on safety since then. For that, the buyers also gained confidence in us. In terms of safety, we think the Bangladeshi factories are the best."

The COVID pandemic worsened the challenges for workers in the RMG industry. Due to the significant drop in demand for clothing, many factories closed, and workers lost their jobs, leaving them without income to support their families.

The Bangladeshi government and international organisations launched initiatives to support RMG workers, such as emergency cash transfers and financial aid. However, these initiatives are beset with challenges, including limited funding and difficulties in reaching all affected workers.

Bangladesh's comparative advantage in low labour and production costs has made it an attractive source for international retail brands. However, this has led factory owners to further cut costs by exploiting workers, leading to poor working conditions and low wages.

These practices have been exposed by tragic incidents like the Rana Plaza collapse, which resulted in the loss of many lives. As a result, efforts are being made to improve safety and workers' rights in the industry. However, the families of the victims and survivors of the collapse want further safety developments in the RMG industry of Bangladesh so that workers don't face such tragedies again in the future.

(All photos by Piyas Biswas.)