IN AN ERA where nations grapple with questions of governance, identity, and international obligations, it becomes imperative to inquire into the source of authority and its legitimacy and legality. This is not merely a question of fact, but it has profound relevance in international law. In international law on the recognition of States, recognition of a new State hinges on the legitimate source of sovereign power. In the Indian context, such an inquiry reveals the robust foundations of the Republic of India, rooted in popular consent and peaceful transfer of power for former sovereigns.

From divine sanction to popular consent as the basis of sovereignty

Historically, the locus of sovereign power has evolved dramatically. In medieval Europe, authority was often ascribed to divinity, as seen in the divine right of kings espoused by thinkers like James I of England. The monarch's will was deemed infallible, deriving from God's mandate, with no room for human contestation. This theocratic model persisted in various forms across empires, including colonial regimes where European powers justified rule over colonies as a civilizing mission ordained by higher powers.

The shift began with the Enlightenment and revolutions that emphasized human agency. The American Revolution (1776) and French Revolution (1789) pivoted sovereignty toward the "consent of the governed," as articulated in the U.S. Declaration of Independence and Rousseau's social contract theory. Consent could be acquired through revolution—violent overthrow of tyrants—or peaceful transfer, such as electoral mandates or negotiated handovers. This transition marked the decline of divine legitimacy and the rise of democratic ideals.

Legal positivism and the reshaping of sovereign power

The ascent of legal positivism in the 19th century further refined this evolution. Pioneered by John Austin, positivism posited law as the command of a sovereign backed by sanctions, divorced from moral or divine considerations. Austin's "Province of Jurisprudence Determined" (1832) argued that sovereignty resides in a determinate human superior, not God or abstract reason. This separated "is" from "ought," focusing on empirical sources of law. Influenced by Bentham's utilitarianism, positivism influenced modern statecraft by grounding authority in observable facts: the sovereign's ability to command obedience.

However, positivism's emphasis on command inadvertently highlighted the need for legitimacy. Critics like H.L.A. Hart noted that raw power lacks stability without acceptance. Thus, positivism paved the way for the "will of the people" theory, where sovereignty emanates from collective consent, formalized through constitutions or elections. In international law, this is echoed in principles like self-determination, as in UN Charter Article 1(2). By the 20th century, decolonization movements worldwide adopted this paradigm, rejecting imperial divinity for popular sovereignty.

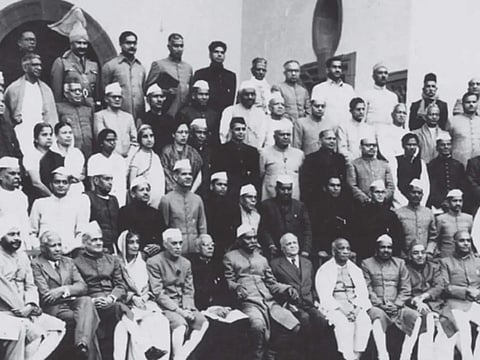

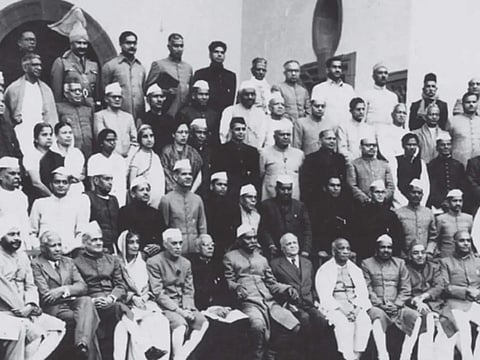

The transfer of power and the Indian Constituent Assembly

Applying this to India, the Constituent Assembly's power sources reflect this historical journey.

The sovereignty of territory falling in British India and Princely States was vested in the British Crown, historically acquired after a series of Anglo-Indian wars directly or through the agency of the East India Company and treaties. However, the Indian Independence Act, 1947 passed by the British Parliament facilitated a peaceful transfer of power, embodying consent through negotiated independence by the freedom movement under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, a champion of nonviolence. Indian independence is unlike that of other countries from colonialism. Rhodesia is a noted example where the British imperial power left a vacuum because it thought that there was no responsible body like the Indian Constituent Assembly to take charge of the governance and frame its Constitution of self-governance. Rhodesia unilaterally declared its independence in 1965, which went through legal challenges.

The sovereignty of territory falling under British India was transferred under Sections 6 to 8 of the Act of 1947. Section 6 empowered the legislatures of the new Dominions (India and Pakistan) to make laws, including adaptations of existing ones. Section 7 outlined the consequences of partition, such as the lapse of British paramountcy over princely states, rendering them independent sovereigns. Section 8 provided for temporary governance until constitutions were framed.

For princely states—over 560 entities—the source was the Instrument of Accession (IoA), introduced under the Government of India Act, 1935 and utilized in 1947. Rulers signed IoAs to accede to India, ceding control over defense, external affairs, and communications. This was followed by merger agreements, integrating states fully into the Union. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel's diplomacy ensured most mergers by 1949, creating provinces or unions like Rajasthan.

An exception was Jammu and Kashmir, whose Maharaja Hari Singh signed the IoA in October 1947 amid invasion threats. This led to Article 370 in the Constitution, granting temporary special status, allowing a separate constitution and autonomy in internal matters until its abrogation in 2019, when the operation of said Article was neutered by the President of India by a proclamation issued under Article 370(3).

Why the Constitution’s authority remains legally unassailable

The Constitution of India explicitly acknowledges these sources while asserting popular sovereignty. However, the Preamble begins with "We the People of India," proclaiming the document's adoption by the populace, not imposed by external or divine forces. This echoes Lockean consent, where authority derives from the governed.

Article 395 repeals the Indian Independence Act, 1947 and the Government of India Act 1935, severing colonial ties and affirming the Constitution as the supreme law from November 26, 1949 which was enforced January 26, 1950 which came to be known as the Republic Day. This repeal symbolizes the transfer of legitimacy from British statutes to Indian self-rule. Further, Article 363 bars courts from interfering in disputes arising from pre-Constitution treaties or agreements, including IoAs and mergers. This protects the foundational pacts from judicial scrutiny, ensuring stability. The proviso to Article 131 reinforces this: while granting the Supreme Court original jurisdiction in Union-State disputes, it excludes matters covered by Article 363, preventing challenges to accession instruments. The State succession is addressed in Articles 294 and 295. Article 294 vests the Union and states as successors to the Dominion of India's properties, rights, and liabilities. Article 295 extends this to princely states, ensuring seamless transfer from rulers to the Republic. These provisions embody international law principles later codified under the Vienna Convention on Succession of States (1978), treating India as a successor state to British India and the integrated principalities.

Collectively, these elements render the Constitution legitimate and unassailable in law. Its framers, drawing from positivist separation of law and morality, embedded consent as the bedrock. Unlike revolutionary upheavals, India's transition was peaceful, with the Assembly representing diverse voices.

In sum, inquiring into the authority's source illuminates India's journey from colonial subjugation to sovereign democracy. Rooted in consent, bolstered by legal instruments like the Independence Act of 1947 and Instruments of Accession, and self-affirmed through the Constitution, India's framework stands as a model of legitimate governance. In a world of contested sovereignties—from Ukraine to Taiwan—this underscores the enduring power of the people's will.

Note: This article is an edited version of a speech delivered by Senior Advocate Mohan V. Katarki on November 29, 2025 at the K.H. Patil School of Law, Bengaluru