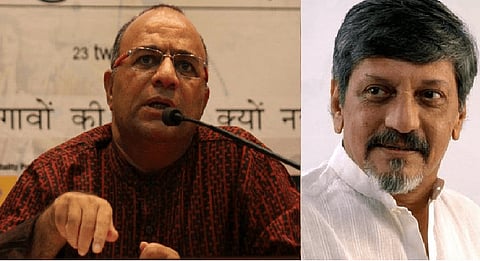

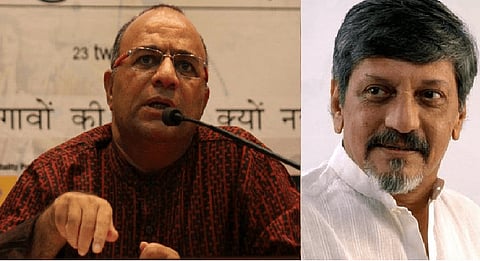

Earlier this year, acclaimed film makers –Mr. Amol Palekar and Dr. Chandraprakash Dwivedi ("petitioners") had filed a Writ Petition in the Supreme Court seeking to challenge the constitutional validity of certain provisions[1] of the Cinematograph Act, 1952 ("Act") and the Cinematograph (Certification) Rules, 1983 ("Rules"). They have filed this petition as they have faced multiple direct challenges with the Central Board of Film Certification ("CBFC") such as cuts, deletions, alterations, denial of certifications in the past and to challenge the same they have had to often approach the Courts for reliefs. Several of their films such as Kissa Kursi Ka (1977), Hawayein (2003), and documentaries such as No Fire Zone: The Killing Fields of Sri Lankahave been denied for release in public space altogether. Hence, they have specifically challenged the CBFC's power of ordering cuts, deletions, alterations in any film along with the abuse of power while certifying and/or denying certification to any applicant film. Petitioners assert that these provisions impose pre-censorship on the freedom of speech and expression of the artistes as well as the audience who is deprived of the opportunity of viewing hundreds of cinematograph films as were conceived and created by its respective makers and thus violates Articles 14, 19 and 21.

The grievance of the petitioners is not a stand-alone claim, this treatment by the CBFC is rather commonly practiced by giving flimsy justifications. Few films in such a category include Aandhi (1975), which was banned for political reasons during Emergency and was released in 1977 even though it depicts the inter-personal relationship between an estranged couple that meet after several years and at different stations in life.

Another film is The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011), which is a fictional psychological-thriller (English) film, whose certification was withheld pending deletion of scenes involving rape and torture and the filmmakers refused to concede and eventually was not released in India. Similarly, in Udta Punjab (2016), a film exploring drugs use and abuse, certification was withheld with a demand for about 90 cuts as was stated was based on political motives. This film was later permitted to be released with the nominal modifications by the Bombay High Court. Likewise, most recently, Padmavati which is based on a poem Padmavat by Malik Muhammad Jayasi and narrates the story of a Rajput queen has also been delayed indefinite because of numerous controversies and is thus pending approval by the CBFC.

The various grounds for challenging the provisions, namely: Sections 2, 3(1), 4(1)(iii), 5(1) & (2), 5A(1) of the Cinematograph Act, 1952 ("Act") and Guidelines 1 and 2 dated December 6, 1991 ("Guidelines") formed under the Act and the Cinematograph (Certification) Rules, 1983 ("Rules"), in Mr. Amol Palekar and Dr. Chandraprakash Dwivedi's petition are:

Therefore, the petitioners state that since the Act suffers from so many inadequacies and defects, hampering the fundamental rights of the Petitioners and other Indian citizens that the challenged provisions should be declared invalid.

[1]Sections 2, 3(1), 4(1)(iii), 5(1) & (2), 5A(1) of the Cinematograph Act, 1952 ("Act") and Guidelines 1 and 2 dated December 6, 1991 ("Guidelines") formed under the Act and the Cinematograph (Certification) Rules, 1983 ("Rules").

[2] on the application of Section 4(1)(iii) of the Act.

[3] Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, (2015) 5 SCC 1 is relied upon.

[4] in Section 5B(1) of the Act.