Excessive government advertisements used by political leaders for publicity are a threat to democracy. It is time to take a closer look at government spending in advertising and analyse the issue from a democratic perspective, writes ANURAG TIWARY.

————————-

THE Madras High Court recently held in an order that governments must take extreme care and caution to ensure that public funds are not being used by political leaders for publicity purposes.

Although this statement was made by the court in the context of a very specific issue regarding the printing of photographs of public functionaries on stationery items to be distributed to school students in Tamil Nadu, it is still a good starting point to contextually analyse the debate around government advertisements.

In doing so, this piece will not just revolve around the usual economic arguments raised against government advertisements, but will also focus on the debate that raises important concerns around democracy.

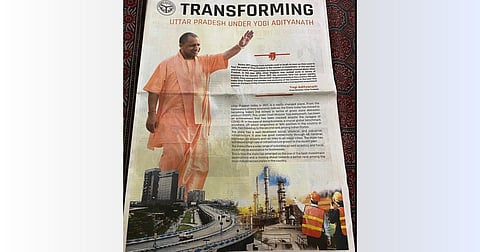

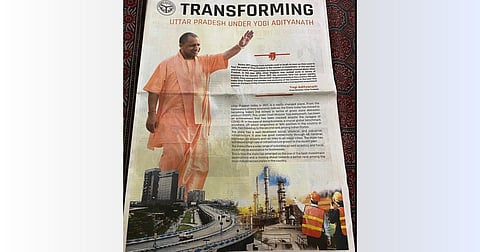

Ever since the Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Adityanath was summoned to Delhi by the BJP's national leadership in March this year over growing concerns against his administration's mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic in the state, there seems to have been set a strange precedent in the country. The national capital is littered with billboards featuring Yogi and his 'No. 1 Uttar Pradesh' campaign, and newspapers are crammed with advertisements that look like news reports, commending Adityanath for his "incredible work".

What explains this huge investment in advertising could be the UP state election scheduled to be held early next year. However, what is unfortunate are two specific unprecedented developments that have transpired in its wake.

Firstly, most of these advertisements are focused outside the state of Uttar Pradesh and are spread in different parts of the country like Delhi and Karnataka whose residents derive no value from advertisements that focus on the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh.

Secondly, Chief Ministers of other Bharatiya Janta Party-ruled states have seized this opportunity and are following suit. Pushkar Singh Dhami (Uttarakhand), Himanta Biswa Sarma (Assam) and Jairam Thakur (Himachal Pradesh) are among the top competitors in this regard, with advertisements touting their achievements splashed across national newspapers as well as in at least central Delhi, where I have observed the same.

“The trend of late is that these advertisements are consciously disguised to appear like news reports published by journalists. They lack clearly-visible disclaimers, and it is increasingly difficult to spot the difference between an advertisement and a news report, unless examined closely. These are thus likely to cause confusion in the minds of the viewers/readers who are bombarded with advertorials on TV, newspapers, magazines, and roads, and might form false impressions of facts based on these.

This raises several important questions about the ethics of this design and the opportunity costs that we, as a democracy, are incurring.

Criticism surrounding government advertisements has hitherto analysed the issue only from an economic perspective, in that, it argued that the scale of public investment going towards promotional activities for the government would be better spent on welfare or developmental work.

However, it may be useful to consider the excessive nature of advertorials from a political and especially democratic lens. There are at least three important questions that can be raised.

First – Do excessive government advertisements, which have no informational value, create a diminishing level playing field for other political parties who are also in the electoral fray? Smaller regional parties who fail to counter the narrative because of their inability to garner the necessary financial resources to put out advertising are at a clear disadvantage.

Second – Does this also promote information asymmetry among citizens and make room for a lack of informed consent on the part of voters who exercise their ballot with the limited and conditioned information that is pushed through these advertorials?

Third – What is the "public value", if any, derived out of such advertisements?

Governments may respond to these concerns by claiming that advertisements help spread "information and awareness" about social security initiatives taken up by the State.

However, there seems to be little truth to this argument, which is at best, a canard. Most of these advertisements usually tend to promote key leadership figures in the government. For instance, one of the advertorials published by Time Magazine for the Uttar Pradesh government read "Being positive in a negative situation is not naïve. It is leadership. No other leader exemplifies this better than the U.P. CM Yogi Adityanath".

Furthermore, presuming that some value is actually being derived from such advertisements, who is to ensure that the proclamations made in these advertisements are true and are not false or manipulative? Is it even possible to objectively certify that. Adityanath is so positive in a negative situation that there is no other leader who can exemplify such behaviour?

The Harvard Business Review last year published an interesting report titled "Advertisement makes us unhappy". A team of researchers headed by the University of Warwick's Andrew Oswald found an inverse connection between advertisements and the overall happiness of individuals. The more you advertise, the higher the chance that your citizens will be unhappy, the report found.

The Supreme Court has remained mostly silent on this issue, precisely because it was forced to prioritize the supposed 'informational value' of these advertisements. In response to a public interest litigation filed in 2015 before the apex court seeking strict rules to check those in power from using taxpayers' money to gain political mileage, the Supreme Court ended up further complicating the issue, with its order being touted as rather contradictory.

While on one hand, in its original judgment in 2015, the court said that any "linking of personalities with social benefit schemes is antithesis to democracy", on the other hand it allowed the Prime Minister's, President's and the Chief Justice of India's photos to be published in advertisements". In a 2016 order, this was extended to the Governors and the Chief Ministers and Cabinet Ministers of the states.

The Print Media Advertisement Policy 2020, also fails to answer the democratic concerns that have been raised in this piece.

It is now time to resolve the issue by gathering evidence through a democratic lens.

(Anurag Tiwary is an 'Impact Fellow' at Global Governance Initiative (GGI) and a final-year undergraduate law student at the Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University, Visakhapatnam. The views expressed are personal.)