The controversies over the ban on wearing hijab by Muslim women students, the exception to marital rape, and the mandatory playing of the national anthem in cinema halls vindicate the relevance of different facets of the Preamble to the Indian Constitution, writes APARNA TIWARI.

—-

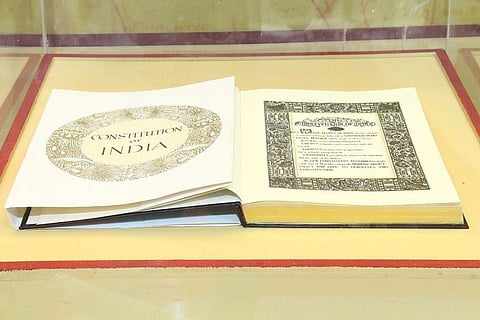

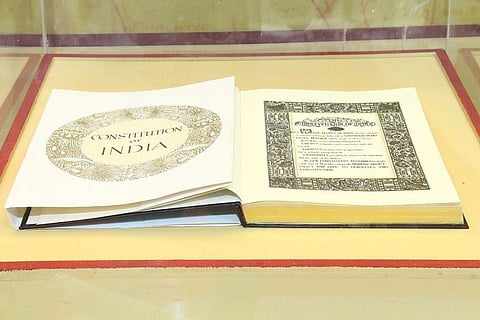

A cursory reading of the texts on the Indian Freedom Struggle shall illustrate that our fight for independence was marked with an unrelenting desire to be governed by our own Constitution, one that's drafted by us and for us. WE, THE PEOPLE have given to ourselves this Constitution, as the Preamble proudly proclaims. The Constituent Assembly was formed after much effort on part of our forefathers and it was with utmost sincerity and sacred devotion with which the Constitution framers drafted our Constitution. It took them close to three years to breathe life into it, a document, revolutionary at the time of its commencement and vibrant even today. This document, drafted in the yesteryears, fills me up with wonder as it continues to present the solution to every problem and an answer to every question.

Indeed, the Constitution is there to guide us and yet, we often tend to forget to turn to it or even consult it before taking big decisions. The ramifications of these decisions may not be glaring always, but sometimes, they are huge and make the nation suffer. In the 73rd year of the Republic of India, let us unwind and take a walk down the Constitutional lane, shall we?

One of the basic features of the Constitution of India is that it embodies secularism- Dharma Nirpekshta, as has been held by the Supreme Court in the case of S.R. Bommai vs. Union of India (1994). Indian secularism by nature is vastly different from western secularism. Secularism in the west, for instance in France, refers to absolute freedom of the state and its affairs from religion. India on the other hand, as envisioned by the Constitution, believes in 'mutual respect' amongst distinct religious communities and not merely 'mutual tolerance', meaning thereby that pluralism is not tolerated but rather, cherished and celebrated here. Accordingly, the state represents no religion as the state religion, treats all religions equally giving everyone the right to freely profess, practise and propagate their own religion and does not discriminate between people of different religions. This is the kind of state that the Constitution stands for.

Therefore, when a government college in Karnataka bans the wearing of hijab during class hours to maintain 'uniformity' amongst students, it raises two issues. First, India is a nation that professes 'unity in diversity' and attaining uniformity has never been the Constitutional goal. Second, that in doing so, the college is defying the very fabric of the Constitution of India. India shall be a sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic republic; that's what the Preamble says. Wearing a headscarf is an essential tenet in Islam and many Muslim women identify with it. For those who do, it's their fundamental right to wear it as guaranteed to them under Article 25 and denying them this right is a violation of Article 14.

It has been held by the Supreme Court in Hindu Religious Endowments, Madras vs. Sri Lakshmindra Thirtha Swamiar of Shirur Mutt (1954) that the freedom of religion in our Constitution extends to religious practices also. India is a multi-religious pluralistic society and the state has an obligation to secularise its institutions so that the oneness of the nation remains intact. How else would the state promote fraternity which is an essential Constitutional precept?

“Wearing headscarf is an essential tenet in Islam and many Muslim women identify with it. For those who do, it's their fundamental right to wear it as guaranteed to them under Article 25 and denying them this right is a violation of Article 14.

Nonetheless, a writ petition with the title, Resham and another v State of Karnataka has been filed in the Karnataka High Court and the judgment is awaited. The court may right the wrongs of the state but the fact still remains. Why must the state be the perpetrator of such wrongs to begin with?

The second event which draws my attention towards itself with a hope for positive change is the ongoing proceedings in the Delhi High Court in the case of R.I.T. Foundation vs. Union of India. This is the case where the petitioners have prayed for the deletion of Exception 2 to section 375 of the Indian Penal Code, a provision which legalises marital rape. This provision is pioneering the antiquated notions of a patriarchal society where a woman is believed to be her husband's chattel and has no free will of her own. This provision violates the right to bodily autonomy of a married woman, is discriminatory as well as arbitrary and takes away the dignity of a woman. It is the dignity aspect of this argument that I am primarily concerned with here.

The right to live a dignified life is a fundamental right under the right to life. It is inalienable in nature. But why has it been made so? It's because every human life is worthy of honour and respect, regardless of anything else. It is a human right, a right that's not guaranteed to us by virtue of our Constitution but a right that we have always had from the moment we were born and that stays until we die. It's a natural right, a right that's affirmed by the Constitution.

There are two objectives that the Constitution of India seeks to achieve; one is to assure the unity and integrity of the nation and the other is to assure the dignity of the individual. Therefore, an argument that marital rape laws may be misused by women is of no relevance on the sole ground of dignity alone. Even if one woman is violated, the state is duty-bound to protect her.

“Our forefathers envisaged an India of liberty, equality, fraternity and dignity assured to each of her individuals. It was an India where justice was available to all and sundry, irrespective of their sex or marital status.

The Supreme Court has held in the case of In Re: Berubari Union (1997) that the preamble is an aid to the interpretation of the Constitution and a key to the minds of the Constitution framers. In the case of State of Uttar Pradesh vs. Dina Nath Shukla (2018), the same court stated that the Preamble is a manifestation of the basic structure of the Constitution. Our forefathers envisaged an India of liberty, equality, fraternity and dignity assured to each of her individuals. It was an India where justice was available to all and sundry, irrespective of their sex or marital status. The state was entrusted with this responsibility as is evident from the Preamble, Parts III and IV, and the entire text of our Constitution. In addition to all the other sound contentions of the petitioners, this should also be why the state cannot be allowed to look away anymore.

The third incident which I'd like to narrate here relates to a conversation I had with a friend on the eve of Republic Day. We were discussing something when one of us inadvertently drifted away to the National Anthem, the beloved Jana Gana Mana. One thing led to another and after few minutes, we were discussing the case of Shyam Narayan Chouksey vs. Union of India (2018) wherein by an interim order, the Supreme Court had made the playing of the national anthem mandatory in cinema halls. Although subsequently the mandate was lifted in a final order passed in the same case, the issue between my friend and I was something else.

“….The Constitution of India is neither autocratic nor restrictive; rather, it is humble in guaranteeing the right to choice to everyone and sensitive by always reminding us that justice must not only be done but must also be seen to be done.

I had always failed to understand the rationale of the protests relating to the interim order. However, through the course of the conversation, I realised that the compulsion had extracted liberty out of equality while also interfering with the fundamental right to choice on the side. This, in turn, had reduced the pious ritual of standing up to the National Anthem a mindless obedience. I took away two points from that discussion. One, may our National Anthem never have to command respect in a manner similar to Nazi Germany and may it echo forever as a revering prayer through the shores of our souls. Two, that the Constitution of India is neither autocratic nor restrictive; rather, it is humble in guaranteeing the right to choice to everyone and sensitive by always reminding us that justice must not only be done but must also be seen to be done.

WE, THE PEOPLE, having resolved, WE, THE PEOPLE must show up. May each of us, the state, you, and me, find the courage to let things take the Constitutional course. Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high.

(Aparna Tiwari is a lawyer, currently preparing for the judicial services examination. The views expressed are personal.)