Due process guarantees should have been a part of the Constitution, says author and lawyer, Rohan J. Alva

During a book discussion, Alva traced the history of due process guarantees through Constituent Assembly debates.

—–

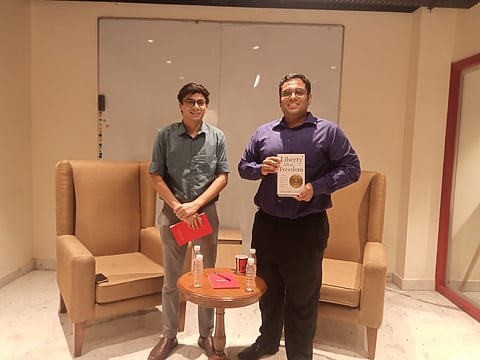

ON May 20, the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, an independent legal research think-tank, conducted a discussion on the book 'Liberty After Freedom: A History of Article 21, Due Process and the Constitution of India', published earlier this year, written by lawyer and author Rohan J. Alva, in conversation with Lalit Panda, Senior Resident Fellow, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.

Alva is a counsel practising at the Supreme Court of India. He earned his LL.M. from the Harvard Law School, where he focused on constitutional law.

Article 21 is one of the shortest worded rights of the Constitution, yet its constitutional impact is one of the widest. The book tries to explain the controversial history of what we now know as the "procedure established by law" in protecting life and personal liberty.

The term 'procedure established by law' was inspired by the 'due process' guarantees which are present in the Constitution of the United States, yet constitutional drafters trace its route from the Constitution of Japan. The book answers why 'procedure established by law' and not 'due process' ultimately found its place in the final draft Constitution.

The importance of due process guarantees

The conversation began with the author tracing the history of Article 21. Panda asked him how he had been able to perceive the history of one of the most important fundamental rights of the Constitution, and what role the due process guarantees played in the Constituent Assembly debates.

“The due process guarantees were primarily born out of historical necessity because they offered the ability to protect rights and the rule of law against the extraordinary trauma inflicted by the British rule on India.

The Constituent Assembly was tasked to create an individual zone of freedom which is free from State interference. This was envisaged in a form of Fundamental Rights which are now found in Part III of the Constitution. The due process guarantees were primarily born out of historical necessity because they offered the ability to protect rights and the rule of law against the extraordinary trauma inflicted by the British rule on India, Alva stated.

Why is Article 21 devoid of due process guarantees?

Alva pointed out two initial issues that the Constituent Assembly was faced with while trying to give a shape to the due process guarantees. B.N. Rau, the Constitutional Advisor to the Constituent Assembly, suggested to the Assembly to do away with the due process provision because the American experience with it had not been good.

Two members of the Fundamental Rights sub-committee of the Constituent Assembly, Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar and K.M. Munshi, in March 1947 had suggested that America's approach to include the due process guarantees was in general terms, and that is why it came upon the Supreme Court of the United States to later interpret and limit the rights falling under it.

Due process finds its origins in the 5th Amendment and in Section 1 of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The members stated that the later Constitutions did not follow this approach and rather defined due process guarantees with limitations after studying the judicial interpretations of the American Bill of Rights.

Munshi in his 'Note and Draft Articles on Fundamental Rights' of March 17, 1947, included due process guarantees under Article V(4) as, "No person shall be deprived of his life, liberty or property without due process of law."

Alva stated that the Drafting Committee did not follow the American example. However, it was able to find a similar provision under Article 31 of the Japanese Constitution which used the term 'procedure established by law' and simply copied it. It did not understand its future implications. After having extensively debated the inclusion of due process guarantees, the drafting committee did not even acknowledge it in the final draft, according to Alva.

In this context, Panda then asked him about the operationalization of Article 21 in the context of interpreting the rights of LGBTQI+ persons, abortion rights, detention and physical liberty, and protecting human dignity in contemporary times. Panda expressed his concerns over the wide interpretation of Article 21 because the meaning of life and personal liberty is constantly changing.

Answering this question, Alva pointed out that the same issue was also experienced by the Constituent Assembly. The sub-committee on fundamental rights, under the aegis of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, studied the due process guarantees extensively. They tried to debate issues like unwarranted detention and other related un-enumerated rights, whether the due process guarantees can be kept outside judicial review and whether due process applies to property rights or not.

The history of this provision, Alva argued, is essential to understand its present interpretation, especially in terms of un-enumerated rights such as privacy and homosexuality.

“The Drafting Committee did not follow the American example. However, it was able to find a similar provision under Article 31 of the Japanese Constitution, which used the term 'procedure established by law' and simply copied it. It did not understand its future implications.

However, the committee came to the conclusion that life and personal liberty, as a part of the due process guarantees, deserve the highest importance. Unlike the U.S., due process in India cannot be stretched out to apply to property rights because that would make it difficult to abolish the Zamindari system, ultimately threatening the future land reforms.

There was another suggestion, Alva pointed out, to make the laws of social welfare immune from judicial review, rather than including a provision that offers due process guarantees. That is why Ayyar, Munshi and Rau again suggested including the due process provision because they knew that this provision has the ability to be widely interpreted. But that suggestion was rejected. Instead, the drafting committee came up with what is presently known as Article 21.

Panda asked a follow-up question on the motive of the drafting committee to include the phrase 'procedure established by law'. He stated that due process is a safeguard which reflects a standard of sufficiency for the courts to understand the reasons on the basis of which certain rights can be taken away or not.

Alva responded that it is difficult to trace the motive of the drafting committee because the Assembly spent sufficient time debating on the due process guarantees, but the final draft did not even have it mentioned. It is indeed visible, he observed, that the drafting committee went against the decision of the Assembly.

Further, he said, it is interesting to note that Ayyar definitely wanted to include due process in the final draft of the Constitution. But when the drafting committee came out with Article 21, he became one of its biggest proponents. So, the original intent is hard to trace, as per Alva.

Procedure established by law does not ensure enough safeguards

Further, Alva said, the drafting committee copied the Japanese Constitution but failed to give any meaning to the term 'procedure established by law'. The present Article 21 is a mix of Article 31 of the Japanese Constitution and the Irish Constitution's Article 40(4)(1), from which the term 'personal liberty' has been borrowed. Alva pointed out that Rau was completely against this provision from the Irish Constitution because it afforded little protection against oppressive State action. This provision allowed the state to override the personal liberty right by simply passing a law to that effect. But in the end, he commented, these considerations were not taken up by the drafting committee.

Panda asked perhaps if that is the reason why courts feel that since due process was rejected as a whole, any fragments of due process should also not be considered.

“The drafting committee was confused. The committee did not want to include property rights within the purview of due process. But then the right to property was included as a fundamental right under Article 19(1)(f), in which due process guarantees in the form of 'reasonable restrictions' are present.

Alva averred that the main issue comes down to the fact that the drafting committee was confused. The committee did not want to include property rights within the purview of due process. But then the right to property was included as a fundamental right under Article 19(1)(f), in which due process guarantees in the form of 'reasonable restrictions' are present.

Also, in a similar context, Alva noted that since there is a due process guarantee in Article 19, we have been able to create a justified framework to interpret the overarching and far-reaching interpretation of Article 21.

Lastly, Panda asked if the test of proportionality recognised in the Puttaswamy judgment of 2017 would be able to provide some guidance to courts on the interpretation of procedure established by law. Alva said that proportionality is not enough indication, considering the fact that life and liberty have been given the highest importance in the Constitution.