The experience of law from the eyes of the litigant can be both bewitching and shocking. MOIN QAZI, a development professional and former banker, narrates how he navigated the law and courts.

———-

ONE of the toughest tasks I had to handle in my long career as a banker was handling recalcitrant defaulters who made us literally beseech when they refused to pay up the loan. Personal experience taught me that when clients need loans, they will make countless trips to the bank to beseech the manager for help with obsequious supplications. Once the loan is released, however, most of them start behaving like wily debtors who can be tamed only by the mythical kabuliwalas!

Bank officials have to waste precious time in obtaining an acknowledgement of debt, to ensure that the bank doesn't lose its claim over the loan.

The statute of limitation stipulates that, in case of default of debt, the claim must be invoked within a prescribed time limit, normally three years. Before the end of that third year, borrowers start performing vanishing tricks, because they know that deferring the payment would permanently absolve them of their liability to the bank.

“My humble, polite voice chimed oddly amid the thundering concluding part of the speech of top-rank lawyers intended to inspire enthusiasm in the audience.

Collecting these documents is one of the most humiliating experiences a bank manager can have. Villagers play clever hide-and-seek games with the manager, who may have to return empty-handed to his bank even after spending an entire day scouring the village.

The basic spirit behind the statute is that there should be a reasonable period during which the bank may take action against the borrower. Bankers do not want to file lawsuits against erring borrowers, especially in the case of smaller loans. Since lawsuits are both time-consuming and drain precious manpower resources and other expenditures, banks try to use the traditional methods for recovery of dues.

Court proceedings will sometimes turn into such protracted odysseys that it is not unusual for the litigation to long survive the litigants themselves.

I had to periodically take the witness stand in the mofussil courts for tendering evidence in lawsuits against such chronic defaulters and those who would evade the signing of documents for renewing their debt. The experience in each case would follow a common narrative.

“Indeed, it is fair to say that the whole justice system is built on the foundation of not telling the whole truth.

Lawyers thrive on promises and defaulters prefer paying heavy fees to lawyers rather than redeeming their debts.

It seems that the courtroom oath–"to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth", is applicable only to witnesses. Prosecutors, defence attorneys, and judges don't take this oath–they needn't!

Indeed, it is fair to say that the whole justice system is built on the foundation of not telling the whole truth.

It is the job of the defence attorney—especially when representing the guilty—to prevent, by all lawful means, the "whole truth" from coming out". On the other hand, the prosecutor is trained to ferret out the truth, the defence attorneys usually outsmart them by putting them off track.

I entered the courtroom and sat just below the judge's bench. My encounter in the witness box left my ideals evaporating. As I took my place in the dock, my lawyer hurried into the court. He saw me and raised his thumb.

The defence lawyer had amassed a lot of evidence. I was confronted with a dizzying number of exhibits—notices, bank vouchers, signed cheques, correspondence. They were spun out of the lawyers bag, as my lawyer and the defendant's lawyer sparred over legal issues.

“If the law is against you, pound the facts. And if both are against you, pound the table!

The defence lawyer tried to chip at my credibility as he proceeded to grill me in near-perfect theatrical slang with a cannon fire of questions:

"Did the borrower sign in your presence?"

"Were the contents of the documents explained to him?"

"Can you produce any witnesses in support of your argument?"

He tried to play a smart game and questioned every simple line of logic.

Painfully aware of how words skate over and around truth, never having quite enough nuance to grasp it completely, I contested him equally forcefully, testifying in blunt terms. At stake was a loan of Rs 25,000 and the lawyers were battling as if the country's sovereignty was at stake.

The defence lawyer was gesticulating with ferocious gravitas. He reminded me of the famous aphorism: If the facts are against you, pound the law. If the law is against you, pound the facts. And if both are against you, pound the table!

My lawyer couldn't respond suitably. He kept skirting around the law. His usual refrain would be, "Your Lordship, this is a leading question." It appeared that his strategy was to wear out the defence lawyer or elicit some favourable response from the Magistrate, who kept on overruling the objections. The judge pronounced: "The court has found no violations." Perhaps an individual judge may be biased, I thought at that time, but the judicial system as a whole can't ignore both the law and self-evident facts.

My lawyer tried to inject some hysteria in the courtroom in order to impress me. He would keep banging the table while making his point. This is not surprising.

“The Magistrate seemed to be conscious of being a deity in his own small kingdom in which he exercised unbridled authority.

I tried to reason with the Magistrate that, if I had known that each loan could generate a thriving cottage industry of litigation and lead me through a painful odyssey, I would have restrained my enthusiasm. I was animated with a passion for helping the poor and now I found that I had become trapped in a multiple helix.

My humble, polite voice chimed oddly amid the thundering concluding part of the speech of top-rank lawyers intended to inspire enthusiasm in the audience.

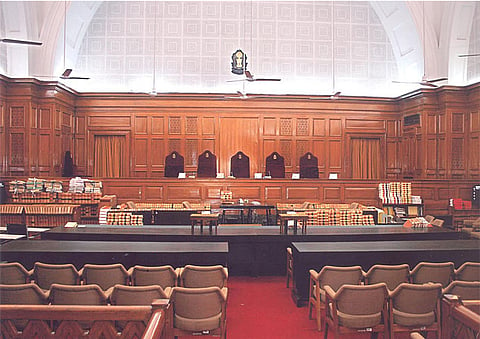

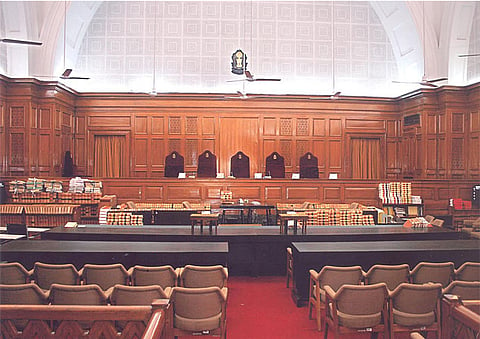

The Magistrate seemed to have been offended by my remark. It was as if he sat on Vikramaditya's throne and lesser mortals like me dared not use his court for moral philosophizing. In front of me sat the philosopher king, the flag-bearer of the cloistered virtue that is justice, holding the court in its majestic grandeur, and I was a supplicant who had the temerity to dispense his own version of wisdom.

The Magistrate seemed to be conscious of being a deity in his own small kingdom in which he exercised unbridled authority. He appeared quite patronizing, dispensing justice the way a modern saint dispenses benedictions. For him, everyone who entered the witness box was someone who was arraigned before his stern tribune of justice. He grimaced at my audacity and his face wore a straight, grim line as if to say, "We know the law better."

“Looming in front of me was the lofty majesty of law in whose shadow stood a puny creature.

The regulations of the judiciary are broad enough to be used punitively by small-minded judges. Earlier in the day, a colleague had been up in a much uglier fashion. It was a field day for the Magistrate, slamming people from the banking fraternity to the undisguised delight of the chattering lawyers.

Standing in the hallowed precincts of the temple of justice, I shuddered, wondering whether the Magistrate would frame me for lowering the dignity and prestige of the court. Looming in front of me was the lofty majesty of law in whose shadow stood a puny creature. The judiciary should not move into such narrow straits and shallow shoals. St. Luke in the Bible abjured the physician thus: "Physician, heal thyself!"

A responsive and robust justice delivery system is imperative for a country's development. When justice is delayed or not served, there is little hope that things will change. Changes within the justice system are complicated, interlinked and systemic and require long-term, committed critical interventions.

(Moin Qazi is a development policy professional and was a member of NITI Aayog's National Committee for Financial Inclusion. Views are personal.)