The Amarnath yatra base camp and route is still reeling from past environmental damage. Last year, the yatra had fewer pilgrims due to the pandemic. This year, Jammu and Kashmir is reeling under an even worse second wave. The government should use this period to clear the yatra route of plastic waste and set new protocols for cleanliness and waste management that suit the environment and the spiritual nature of this journey, writes RAJA MUZAFFAR BHAT from Srinagar.

—–

THE 2021 annual Amarnath pilgrimage, also known as the Amarnath yatra in Kashmir, is in the offing soon. On 22 April, the Shri Amarnathji Shrine Board (SASB), headed by Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha, suspended online registrations for the yatra as COVID-19 cases were swelling across the country.

It is still unclear if the annual pilgrimage will happen this year, but a limited number of pilgrims may get permission to travel in the first week of July. Every year, the Amaratra starts at the end of June and lasts 45 days. The yatra was staggered last year due to the pandemic, and very few pilgrims were allowed to visit the shrine every day.

In 2018, more than 7,000 pilgrims visited the Amarnathji shrine daily and around 2.85 lakh in total. The yatra was extended and lasted for around two months. The numbers fell in 2019 as the government asked pilgrims and tourists to leave Kashmir on 1 August just before it abrogated Article 370.

The Jammu and Kashmir government had issued a security advisory citing a "terror threat" in the Valley and asked pilgrims and other tourists to leave the Valley as soon as possible. Nobody knew New Delhi had another plan to execute on 5 August 2019.

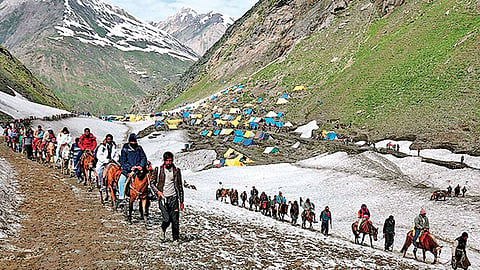

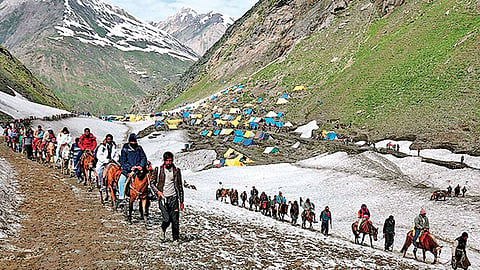

The Shri Amarathji shrine has an iced Shiva lingam located in a cave at an altitude of around 3,882 meters. This holy cave is part of the Amarnath peak, which touches an altitude of 5,188 meters. It is a part of the Himalayan range, located south of the Zojila pass that connects the Kashmir Valley with Ladakh. There are two routes to reach this shrine. One is via Pahalgam in South Kashmir and the other through Baltal Sonamarg in district Ganderbal on the Srinagar-Ladakh highway.

Kalhana Pandit, the 11th-century Kashmiri historian, wrote in his famous book, Rajatarangini (Book VII v.183), about Krishaanth or Amarnath. The belief is that a queen, Suryamati, gifted the Trishul, banalingas and other sacred items to the Amarnathji shrine in the 11th century.

One Buta Malik, a shepherd of Pahalgam, is believed to have rediscovered the Amarnathji cave more than 150 years back. In 2008, the SASB ended the association of the Malik family with Lord Shiva. The three parties—the Pandits of Mattan temple, the Mahant, and the Malik family, were offered one-time settlements to make the SASB the sole guardian of the shrine.

"We were offered Rs. 1.5 crore to give away the custodianship. While other two parties took the money, we refused," Mohammad Afzal Malik had told DNA newspaper, which filed a detailed report on the issue.

The holy cave is in the eastern part of the Kashmir valley. Ever since the annual pilgrimage was extended to a nearly two-month affair (from 2017 onwards), local environmentalists have raised concerns.

Possibly, the Amarnath yatra will commence in the first week of July in 2021. Last year, at a meeting attended by G Kishan Reddy and Jitendra Singh, senior ministers in the Narendra Modi cabinet, the government discussed whether or not pilgrims should be allowed to visit Amarnath and Vaishno Devi, two sacred shrines for Hindus, amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

The meeting, held via video conference, was attended by the then Lieutenant Governor of Jammu and Kashmir, GC Murmu and Chief Secretary BVR Subrahmanyam. The final decision was taken in June and a limited number of pilgrims were allowed for the yatra.

During the 2016 annual yatra, I visited the Chandanwari base camp in Pahalgam with some environmentally conscious friends. It was the end of June and the yatra was going to take off in a few days. I was under the impression that Chandanwari would be a pristine valley surrounded by snow-capped peaks, green pinus trees, and vast meadows.

When we entered Chandanwari through a huge iron gate I was terrified by the condition of the area. Temporary toilets had been installed, but improperly. All the human waste would have leaked during the yatra period. This has been a regular affair for decades.

Garbage was being dumped in the open by local shopkeepers, security personnel and Langarwals. It is pertinent to mention that only a few hundred people were in the area during my visit. So, one can only imagine the environmental impact on the area when more than 7,000 people began to arrive and camp in this tiny area for 45 days. It is hard to imagine the terrible conditions and their environmental impact once the yatra period was extended to 60 days in 2017.

Chandanwari did not have any mechanism for garbage collection, scientific segregation, or treatment. We were told some contractor was given the job of lifting mixed (biodegradable and non-biodegradable) waste, which is then thrown in water bodies and forest areas.

We saw heaps of garbage, PET bottles, and polythene near the banks of the Lidder river which flows through Chandanwari. The unscientific waste management continued even after 2016, including in 2020, in the Baltal and Chandanwari areas.

In 1996, more than 200 Amarnath pilgrims died due to harsh weather conditions. The government constituted a commission of inquiry after that disaster. Headed by Nitesh Sengupta, a 1957 batch IAS officer, it recommended steps for a safe yatra and to protect the environment and ecology. The area is severely threatened during the pilgrimage when, suddenly, massive numbers of pilgrims arrive.

Committees set up by the government have said that the number of yatris needs to be restricted, and polythene use prohibited in and around Pahalgam and en route to the holy cave.

The Sengupta report recommended reducing the number of yatris to the holy cave as well. In 2006, the Jammu and Kashmir State Pollution Control Board also prepared a 37-page report with 25 recommendations. Citing the Municipal Solid Waste Rules, it said not to dump municipal solid waste in forest areas or water bodies.

People visit the Amarnath shrine and cave for spiritual reasons. However, they also engage in anti-nature activities by throwing plastic, food and other wastes in the pristine glaciers, mountains and forests. I do not blame only the yatris, but the local visitors, dhaba-walas, and hoteliers are equally responsible for polluting Pahalgam and Sonmarg on the yatra routes.

Also read: Yatra 2017: Some Suggestions!

The sanitation work in Pahalgam and Sonmarg during the yatra must follow the Municipal Solid Waste Rules, 2016. These rules say that waste has to get treated, not lifted from one place to another. Hired volunteers must undertake Information Education and Communication (IEC) activities during the yatra period.

Each langar must use two bins to segregate the waste generated in langars as biodegradable and non-biodegradable. The automatic waste-composting machines should be available near the dhabas. Biodegradable waste generated at three places—Nunwan, Chandanwari in Pahalgam and Baltal in Sonmarg—should be treated in auto-composters and used as organic fertiliser.

Non-biodegradable waste (plastic/polythene) should be incinerated or processed into pellets and used as fuel in bitumen and cement plants. Small Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) and bio-toilets are also needed to treat human waste regularly. Many other technologies are available to treat liquid waste and should be considered.

The STP at the Nunwan base camp needs an upgrade. Polythene and PET bottles should be completely banned and biodegradable plates and glasses made of banana or other plant leaves should be introduced in the langars. In 2018, this author and like-minded environmental activists made a presentation before the then Governor, NN Vohra (Chairman of the SASB). He was optimistic about managing waste in the area and banning plastic, but his term ended before the 2019 yatra.

I appeal to my brothers and sisters, especially of the Hindu faith, to approach the Amarnath yatra and surrounding areas optimistically. Let this holy and pristine place get some breathing time. Plastic and other non-biodegradable materials have choked the area. The carbon footprint of the yatra has devastated the forests and even glaciers.

The Chandanwari glacier has turned black due to air pollution from diesel gen-sets used in the base camp. Not just pilgrims, hundreds of pony-walas, security personnel and their movements also devastate the environment.

Contractors hired by the SASB are not doing their job well. They do not work on scientific lines. The tendering process does not follow the SWM rules. A few years back, my friends and I visited Baltal Sonamarg at the end of October to see how the SASB contractors managed waste.

I found tons of plastic waste scattered. A team of two dozen volunteers from Srinagar collected at least 200 metric tons of plastic waste at a designated place, which we then packed in sacks and transported to the Srinagar landfill site.

Last year's restricted movement of pilgrims was very helpful to the environment and ecology of the area. It helped contain the spread of COVID-19 as well. This year the pandemic situation is worse in Jammu and Kashmir. The SASB must allow no more than 3,000 people to visit the holy cave, in groups of 50 or 60 persons daily.

Even the pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca was restricted last year and this year. Around 25 or 30 lakh pilgrims visit Mecca on average during the annual Hajj, but Saudi Arabia is considering barring overseas pilgrims for the second year in a row as COVID-19 cases rise globally and worries about new variants grow.

Let the Indian government respect COVID-19 protocols and disallow a huge number of pilgrims to undertake the annual yatra this year as well. The SASB or Pahalgam and Sonamarg development authorities cannot sanitise and clean the area if there is a rush of pilgrims in the summer.

Let the authorities utilise this summer to clear the area of non-biodegradable waste. Plastic waste can be incinerated at different locations on the Baltal and Pahalgam routes. The SASB must consider these suggestions seriously for the sake of the environment and maintain the spiritual aspect of the journey for future travellers to Amarnath.

(Raja Muzaffar Bhat is a Srinagar-based activist, columnist, and independent researcher. He is an Acumen India Fellow. The views expressed are personal.)