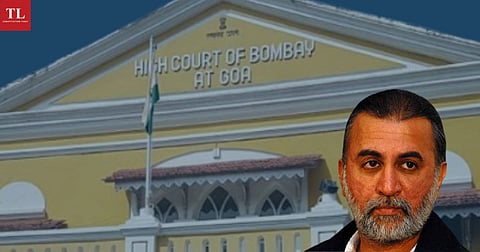

The Goa Government has challenged the trial court judgment that acquitted author and former editor of Tehelka Tarun Tejpal of sexual assault of a colleague during an event in Goa many years ago. Activists and legal luminaries have been critical of the judgment saying that the court put the survivor on trial instead of trying the accused. KAVITA KRISHNAN does a detailed analysis of the judgment dissecting it for readers of The Leaflet.

—–

READING the verdict acquitting former Tehelka editor Tarun Tejpal of rape can be bewildering as essential questions are lost in a disordered jumble of names and details, most of which are not relevant at all. To anchor myself, as I read the 527-page document, I made two columns in my notebook, relating to the two simple questions that are central to the case. And as I waded through the maze of random names and details, I searched for what the court's conclusions were on two questions.

The issue before the court was this:

So the two simple questions facing the court were:

How does the court handle these questions, and what are its conclusions?

We find that the judgment very soon made up its mind that no sexual encounters took place in the lift: the complainant was lying, and cooking up a story of being sexually assaulted. Over and over again, we find the words "manipulative", "evasive", "twisting", "doctoring" and "false" being applied to the complainant.

Remember – the judgment could have concluded that it just cannot be sure enough of the facts to convict. But instead, it repeatedly asserts, with certainty, that the complainant is lying.

If such an assertion is accepted in a judgment, we expect to be told why the complainant lied.

In answer to the question of why she believes the complainant cooked up such elaborate tales of sexual assault, we find that the judgment offers – not one, not two, but a buffet of options:

Each of these wild speculations is flung wildly at us – without any one of them being seriously examined for its merit. The judgment does not tell us which of the above theories it favours: it just throws them out there and (by implication) asks us to take our pick.

These theories are quite vexing.

The complainant might have got grants for ten books; been a member of a feminist community; or had a boyfriend from every continent and country: how would any of it be relevant to her complaint of rape, and why does the court need to be told any of this?

Why did the judge accept and amplify all this rubbish, instead of controlling the courtroom during cross-examination and preventing the defence from trawling indiscriminately through the complainant's messages, emails and privacy to smear and slut-shame her?

Why does the court concede that irrelevant details of the complainant's private life need to be "glossed over", and yet allow those details in the judgment?

The judgment's answers vary according to convenience

The judgment fully accepts the defence of the accused and asserts with confidence that no sexual encounters took place inside the lift. It holds that some drunken banter took place, in which the complainant told the accused some salacious story of her sexual encounter with a VIP guest at the previous year's festival hosted by Tehelka. And according to the court, this story was the context of the text sent by the accused to the complainant late on the night of the alleged assault (saying "fingertips"). This story of so-called sexual banter is sourced from the statement of the accused, supported by the defence witness DW4, supposedly an ex-boyfriend of the complainant, and thus hardly a disinterested witness.

But then, there is the inconvenient question of why the accused wrote two letters of apology to his employee, and one to the Managing Editor of Tehelka. The court explains it thus:

The letters of apology that the accused wrote a) were obtained from him by the Tehelka Managing Editor without his consent and b) did not amount to a confession of sexual assault because he was being pressurised to apologise for his part in the banter that the complainant initiated.

Naturally, if the above narrative is accepted as true, then the second question of consent, becomes irrelevant since the court believes that no sexual encounters took place at all. Yet, what is perplexing is that the judgment is forced, however reluctantly, to use the category of consent/non-consent, when it discusses the letters sent by the accused to the complainant, as well as to the Tehelka managing editor; and when it discusses the CCTV footage of the accused and the complainant exiting the lift on the occasions cited.

The judgment holds that the accused was forced to send the apology letters by the Tehelka managing editor. But in spite of this, the judgment also examines the language of the apologies and says that even in case they were sent with the accused's consent, they do not constitute a confession to "sexual assault, sexual molestation or any criminal offence," but are merely "an attempt to assuage any discomfort" the complainant might have felt after her sexual banter with the accused.

But the question arises: what exactly is the accused apologising so many times for, if in fact all he did was listen to the complainant indulge in sexual banter about some public figure? The judgment uses only negatives to describe it: whatever he is apologising for, according to the judgment, is "not sexual assault", "not sexual molestation". At this point, let us remind ourselves of the language used by the accused in his letters and in other related pieces of evidence.

The judgment notes that the managing editor of Tehelka, on receiving the email from the complainant, angrily confronted the accused who said he had only shared a "fleeting consensual encounter" with the complainant. So here, we are told that the word "consensual encounter" was used by the accused: and we hear this from a defence witness that the court deems trustworthy. The judgment accepts the explanation provided by the defence, that this phrase referred only to the "banter" before entering the lift.

But is it really reasonable that anyone would describe mere talk as a "consensual encounter"? Surely a sexual "encounter" refers usually to a sexual act? If it was a sexual encounter, the accused is claiming it is consensual while the complainant says it was not. In any case, surely this phrase could indicate that some kind of sexual encounter took place inside the lift, as alleged by the complainant? And if so, this phrase surely casts doubt on the defence's claim – which is that the question of "consent" does not arise since no sexual encounter took place at all.

In his "formal" apology, the accused admitted that he was wrong to "attempt a sexual liaison with you on two occasions…despite your clear reluctance that you did not want such attention from me…and there is absolutely no ground or circumstance in which I should have violated the propriety and trust embedded in that relationship."

A sexual liaison despite clearly expressed reluctance is textbook sexual harassment at the workplace at the very least, especially when the court finds the accused to be in a position of dominance and trust. But the judgment dismisses prosecution arguments to this effect, without any serious consideration. Instead, through the language of the judgment, we can clearly hear the voice of the defence, backed by the court's authority and approval, heckling the complainant here, aggressively demanding to know where the accused used the exact phrase "sexual assault" or "sexual molestation" in these letters! If the accused were guilty of sexual assault, why does the court assume he would say so on record? Do guilty persons usually confess to crimes using precise legal terminology?

The formal apology also states, "I acknowledge that I did at one point say to your contention that I was your boss, "That makes it simpler", but I do want to put on record that the moment those words escaped my lips, I retracted them saying "I withdraw that straight away – no relationship of mine has anything at all, ever, to do with that"." Does this line not confirm what the complainant has been saying all along, that she reminded the accused he was her boss, and in reply, he said "That makes it simpler".

Even if one were to accept the claim that he later "retracted" those words, the very fact that an email sent by him admitted to uttering those words in the context of a "sexual liaison" with his employee, suggests that he was misusing the power he held over her as her boss.

Again, the judgment barely even considers the prosecution arguments on this subject; and instead keeps pointing out that there is no admission of "sexual assault/molestation" in this formal letter.

But let us assume for a moment that the formal apology was drafted by the Tehelka managing editor and that the accused agreed to its being sent under duress (as claimed by the defence). Minutes before the formal apology was mailed, the accused emailed a private, "informal apology" to the complainant. In this letter, the accused said "We were playfully and flirtatiously talking about desire, sex,...it was in this frivolous, laughing mood that the encounter took place. I had no idea that you were upset or felt I had been even remotely non-consensual until Tiya came and spoke to me the next night." So, this letter clearly differentiates between what the accused calls "banter", and a separate "encounter" that followed the "banter."

The judgment's interpretation of this "informal" letter is a powerful example of how the judicial gaze is biased against the complainant. The judgment does not record why an informal letter sent by the accused to the complainant, admits that some sexual "encounter" took place. It does not admit this written letter as evidence that some encounter took place, nor does it discuss why the letter refers to "banter" as distinct from "encounter".

The judgment gives a truly fantastic gymnastic performance to avoid this issue, and to conclude that the letter is only referring to banter after all. Here is the relevant paragraph of judicial reasoning:

"It is also important to note here that this statement in the accused's Personal email could not have referred to any kind of "sexual assault" in the lift as the prosecutrix claims, because if this assault had taken place as per her narrative, he would naturally have known of her upsetness, since her narrative claims that she shoved, pushed, pleaded with and struggled against him relentlessly. If he were referring to the alleged incident that she claims happened in the lift, why would he write that he had no idea that the prosecutrix was upset? This statement of the accused makes clear that no such episode occurred in the lift; and no such struggle, pushing, shoving, and pleading happened between them, and that he is referring to the drunken banter he acknowledges they indulged in outside Block 7 for about five minutes…it is clear that the prosecutrix is manipulating an interpretation (of the apology letters) to suit her case."

Take a moment to appreciate what is happening in this paragraph. The judgment scrutinises every word written or uttered by the complainant, suspecting it of being carefully crafted (by her, by feminist lawyers and activists, by her friends, etc) rather than honestly expressed.

However, the same judgment does not subject letters and texts written by the accused to the same suspicious scrutiny. It does not ask itself if these letters might also be employing some strategies to create an impression of innocence.

This judgment accepts as fact the accused's claim in the letter that during the encounter, he did not realise the complainant was upset and cites it to "disprove" the complainant's claim of being assaulted. But the fact is that in most cases of rape, either the accused does not care about consent, or does not even realise that the victim is upset. A rapist is a rapist because he does not empathise with the woman: she is an object to which he feels entitled, and that he dominates and possesses. It is an act of power, in which the rapist ignores the woman's refusals and her pain; and even flatters himself that he has conferred pleasure on her. Hence it is natural that the accused in this case might not know, or admit that he knew how upset the complainant was. Also, women's resistance also is a source of enjoyment for men who rape. Therefore the language of the judgment that it was "natural" for the accused to know and admit in writing to knowing her "upsetness" is incomprehensible.

The strategies of the "non-apology apology" in matters of sexual assault are so familiar as to be boring: the accused tends to make fulsome apologies in a general sense, he talks about her hurt feelings and his own, while carefully avoiding any acknowledgment of the specific non-consensual act he actually committed.

Incredibly, the judgment states that "it is clear" that the complainant "is manipulating an interpretation" of the apology letters "to suit her case." Not for a moment does the court think that the accused might be "manipulating an interpretation to suit his case"!

Note also that these letters by the accused do not ever deny that something happened inside the lift. If indeed he is referring merely to banter outside the lift, and he knows that her complaint refers to two sexual encounters inside the lift, would he not at least say so? But the judgment does not even ask this question.

The letter by the accused shared by the managing editor with the Tehelka staff, is titled "Atonement", and in it, he says that his "lapse of judgement" led to an "unfortunate incident", and thus he is recusing himself from the editorship of Tehelka as a "penance that lacerates me."

The judgment accepts without question that the accused only sent this mail under pressure from the managing editor, and further that he is recusing himself, not as a punishment for a crime he admits to committing, but simply in response to the allegations by the complainant. But if the letter simply communicated a decision to step down due to allegations, why would the subject heading of his letter be "atonement"?

For what mistake or crime is he atoning? Would he really have agreed to remove himself from his editorship for six months, and use heavy words like "atonement", "laceration" and "penance" if the unfortunate incident were merely some "banter" to which he listened helplessly? These are all questions the judgment chooses not to entertain at all.

As one reads this judgment, one is bewildered by the fact that it repeatedly uses a variety of pejorative words to refer to the complainant's testimony and her replies: every answer, every failure to remember tiny details (of conversations and WhatsApp messages from seven years back; of whether or not she moved her chin or raised her legs during the assaults; of whether Yuvraj Singh ever wanted to learn yoga from her, and why she failed to use a smiley in some of her jokes) is described with adjectives such as "evasively" (this word is used 14 times for the complainant) and "brazen", and verbs such as "manipulating", "twisting", "lying".

The complainant said that she afraid of going to the police, because of her boss's clout. The judgment deems this to be a lie, based on the fact that the complainant had once, in Delhi called 100 to complain against a policeman who drew a gun on her friend!

But the same judgment takes every statement by the defence, including letters and text messages sent by the accused to the complainant, at face value. In fact the judgment on several occasions (such as the one about "upsetness" cited above), uses a statement by the accused as a touchstone by which to disprove a statement made by the complainant! In my admittedly limited experience of court judgments, I cannot think of any other example where the judgment uses the statement of the accused as a touchstone, (assumed to be true and innocent of any fabrication, embellishment, silence, evasion etc) in reference to which an allegation by the complainant is held to be false.

There is CCTV footage of the accused and the complainant entering and exiting the lift on two separate days. The judgment notes that the complainant is seen doing up her hair and adjusting her dress on exiting the lift on the first night (07.11.2013), and reproduced granular cross questioning of the complainant on this issue, including questions about how many times on average she redid her hair in one day, was it a habit for her to undo and redo her hair, and so on.

The same footage of the two exiting the lift on the second floor on 07.11.2013, also shows the accused wiping his mouth. The judgment, dare we use the word, "evasively" avoids really thinking about whether his wiping is mouth might tie in with the complainant's claims of oral sexual assault.

On the night of the first assault itself, the complainant had told three of her colleagues about being assaulted. All three bore witness to this in court, as did a fourth whom she had told about the assault a little later. But the testimony of two of these men is dismissed by the judgment as false on the count that they were not really close friends of the complainant, but were friends of her husband. A third testimony is also dismissed because he supposedly had once had a crush on the complainant, and that of a fourth is dismissed because the complainant did not describe her rape in graphic detail to him.

The complainant's partner and mother, both of whom were also told by the complainant about the incident, are also taken to be untruthful.

But the judgment places great reliance on the testimony of one male defence witness (DW4). This witness is a man the complainant saw soon after the assault; she explained that she omitted to mention him in her complaint because he was not answering her messages, and she assumed this was on account of his closeness to the accused's daughter. The judgment accuses the complainant of "brazenly" lying to hide the fact that DW4 was a former boyfriend of hers, who thus "knew her intimately" in a way others did not. Meanwhile, the judgment constructs the figure of DW4 as a moral one – in contrast with the figure of the complainant as "brazen" and promiscuous.

The judgment mentions, for instance, that DW4 made it a point to tell his fiancee about meeting his ex (the complainant).

It is DW4's testimony that is the main vehicle for a large part of the slut-shaming in the judgment.

DW4 says it was "routine for the prosecutrix to have such sexual conversation with friends"; on the strength of this, the judgment concludes that the complainant did narrate the story about a sexual encounter with a VIP guest, to the accused.

DW4 also testifies that the complainant told him the same story, thus lending weight to the accused's claim that he too was told the same story by her as "banter".

DW4 adds that the complainant cheerfully told him on the night of the incident that she had flirted with the accused, and that he had reacted with shocked disgust, asking her "Are you going to spare no one?" (Again, this performance of shock and disgust is recorded by the judgment, helping to establish DW4 as a "moral man".) DW4 also names others he claims the complainant was having sexual relationships with.

The thing is, this story of the complainant's sexual encounter with a VIP guest the previous year is a defence story: it does not get established as fact, that too if the witness DW4 who claims to be corroborating it is accepted by the court to be an ex-boyfriend of the complainant. How does DW4's status as a former boyfriend make him a more reliable commentator on the character and actions of the complainant, than her own friends and colleagues?

Surely as an ex-boyfriend, DW4 might have an axe to grind in publicly slut-shaming her and claiming she is a promiscuous liar?

Why is his testimony seen as sterling in spite of being an ex-boyfriend who is not likely to be objective about his ex-girlfriend, while three journalists who are the complainant's colleagues are dismissed as liars because they know her partner as well?

Newspaper reports have claimed on the basis of the judgment, that the Goa prosecution "destroyed" CCTV footage of the first-floor corridor of the hotel, which if available would have exonerated the accused. This, on closer examination, is a false claim.

CCTV footage of all three floors had been obtained and stored in a court property room. Footage of the first floor, stored on a DVR, became damaged. In January 2021, for the first time in seven years, the accused claimed that in fact he and the complainant had exited on the first floor accidentally, which explained why they arrived at the second floor from the ground floor in 2 minutes 9 seconds instead of 18-20 seconds. He claimed that the footage had been destroyed to prevent his innocence being established – and the judgment accepts this claim without question.

What questions could and should the judgment have asked? Here are some:

A cloned copy of the CCTV footage of all three floors had been given to the accused in 2015. So he too had a copy of the complete footage which is presumably undamaged. Why did he not show his copy to the court as evidence? If he had not been given the first-floor footage, why did he never say so all these seven years? Suddenly, in January 2021, on knowing that the first-floor footage in the state's possession is damaged, his defence remembers that he and the complainant exited on the first floor?! But the judgment as usual has nothing to say about the accused's convenient memory: those remarks are reserved for the complainant when she fails to remember whether or not she moved her chin and lifted her legs during the assault.

For seven years, the complainant did not have the same advantage that the accused did, of having access to this footage to prepare for her testimony by watching the footage. Yet the court expects her to remember every little detail and when she cannot, disparages her for a "convenient memory."

Defenders of the accused claim he is being politically victimised by the BJP through a false rape complaint.

The judgment, though, displays a notable bias against the complainant's politics, specifically her feminist politics.

Ask yourself why the judgment chooses to single out the complainant's Instagram post on the Hathras case? The post read: "Trigger warning. Governments do not care about women's safety, their lives or their agency. In a case that suits their political agenda, they will move heaven and earth to register a complaint they learned about on Twitter, reject a woman's agency about whether she ever wanted to go to the police, consign her life to the flames. When a Dalit family makes a complaint about their daughter's rape and murder and asks for the law to step in, that complaint falls on deaf ears, her body is consigned to the flames so rape cannot be proved #hathras"

It is true that the approach of governments to the Tejpal case and the Hathras case respectively point to political opportunism on the issue of rape, rather than a consistent feminist concern for justice.

Why, though, did the judgment choose to cite this post at all? Is it perhaps because of a bias against the complainant's principled feminist politics?

The judgment also, likewise, writes that the complainant "admits that she had sent WhatApp messages to Danila – stating "What about the fact that I'm a fearless feminist?"" Why does the judgment think that being a fearless feminist makes the complainant a less credible witness?

It is worth trying to trace, here, where in recent times do we come across the language of a feminist conspiracy. We find it cited in a 2017 challenge by rightwing ideologue Madhu Kishwar to the 2013 amendment. Then we have the unsubstantiated allegations of a feminist conspiracy in the sexual harassment allegation against the then CJI. We see protestors of the Hathras rape, and even journalists who report the rape being arrested as seditious conspirators. More generally we see a discourse that profiles women students, academics and activists in different protest movements, especially the anti CAA protests, as being both sexually promiscuous and seditious.

This political discourse now seems to have been absorbed in the Tejpal rape trial. If membership of WhatsApp groups supporting anti-CAA protests was sees as evidence of conspiracy, now we are seeing a rape complainant's emails and messages to and from feminist lawyers and activists, as evidence of conspiracy.

We need to reflect on how larger social and political discourses converge to treat the testimony by a feminist as a lie, as a conspiracy and as immoral.

Judicial training of women in the bar on feminism in law is urgent to counteract this trend, for a feminist method is central to ensuring a fair trial for rape survivors.

If the Tejpal verdict is allowed to stand, it will set a dangerous precedent for every rape case to come; and will intimidate and deter every rape survivor from seeking justice.

(Kavita Krishnan is Secretary, All India Progressive Women's Association. The views expressed are personal.)