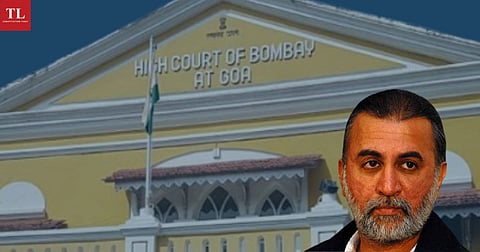

Analysing the recent judgment by a Goa Court acquitting Tarun Tejpal of rape charges, SHOBHA GUPTA writes that it is a manual for how and what not to write in a judgement dealing with a case of sexual violence against a woman.

—-

THE 527 pages long judgment of a Goa Court acquitting the media baron Tarun Tejpal from the allegations of rape and sexual molestation punishable under Sections 376(2)(f) and (k), 354, 354A, 354B and 342 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC), is virtually a manual for how not to deal with a case of rape charges.

Everything in this judgment is wrong: be it the approach of victim blaming adopted by the judge; the tenor of the judgment; the ignorance as well as misinterpretation of legal provisions and law laid down by the Supreme Court; the tilted appreciation of evidence; the permitting of lengthy and torturous cross-examination of the prosecutrix that defy all norms of basic decency; the heavy reliance, with reproduction in the judgment of the questions posed, on the cross-examination by the defence lawyer; the non-shifting of onus upon the accused to prove his innocence; the treatment the accused with kids gloves; the reliance on the past of the prosecutrix and her character assassination; the judge's notion of how a sexual assault or rape victim should ideally behave after being victimized.

The most disappointing aspect is that this is a judgment delivered by a female judge, from whom society would expect more empathy in such cases of crime against women.

Not only has the judge seemed to have proceeded throughout the judgment with a preconceived notion that the prosecutrix does not fit with the stereotypical conduct expected of a 'perfect victim' of rape, but for every single aspect of the prosecution case, the judge is extremely critical, testing it with a razor sharp and rigid approach that has apparently already assumed the conclusion and is reasoning backward from there.

Even the clinching evidence where the victim was seen organising her dress and hair has been dismissed by the judge by referring to other photographs of her to reason that the victim was in a habit of organising her dress and hair. On the other hand, the extremely specious and unconvincing excuses of the accused to explain the apologies given by him in which he clearly admitted his guilt, have been believed by the judge.

Apart from its verdict of acquittal of the accused despite his admission in the apologies he wrote to the victim, the judgment suffers from several vices, one of them being its unnecessary length.

A reading of the judgment shows that the repeated reproduction of the prosecution version of the incident was not only unnecessary, but it was also painful to read the detailing of the alleged violation of the prosecutrix, to the extent of filling a reader with disgust and agony. The judge has repeated the details of prosecution version of the incident ad-nauseam without any reason or justification.

Honestly, on reading the judgment, one may get an impression that the main aim of the judgment was to condemn the prosecutrix for daring to make allegations against the accused. To say the least, the judge has been extremely harsh in her approach and expression towards the prosecutrix, be it disbelieving her version of events, or finding fault with her character.

The judgment sets a bad precedent for how to approach such cases of sexual offences against women. It is a manual for how not to write a judgment in such a matter.

Principles set by Supreme Court to deal with such cases violated

Sexual offences against women have been a major issue in India, and ample efforts have been made to address the issue, be it amending the existing laws, bringing new laws in force, or making attempts to sensitise the stakeholders to approach such matters. There is no dearth of judicial dictum where the Supreme Court has time and again directed the courts to approach such cases with utmost care and sensitivity, keeping in consideration all probabilities of human behaviour and responses which may vary from individual to individual.

The Apex Court, in its judgment in the case of State of Punjab vs. Gurmit Singh & Ors., 1996 SCC (2) 384 almost a quarter of a century back, had shown its displeasure about the manner in which courts show little or no sensitivity while dealing with cases of crime against women. The Supreme Court observed:

"Of late, crime against women in general and rape in particular is on the increase. It is an irony that while we are celebrating women's rights in all spheres, we show little or no concern for her honour. It is a sad reflection on the attitude of indifference of the society towards the violation of human dignity of the victims of sex crimes. … The Courts, therefore, shoulder a great responsibility while trying an accused on charges of rape. They must deal with such cases with utmost sensitivity. The Courts should examine the broader probabilities of a case and not get swayed by minor contradictions or insignificant discrepancies in the statement of the prosecutrix, which are not of a fatal nature, to throw out an otherwise reliable prosecution case. … [T]he trial court must be alive to its responsibility and be sensitive while dealing with cases involving sexual molestation." [Emphasis added]

The court further held in this judgment:

"Inferences have to be drawn from a given set of facts and circumstances with realistic diversity and not dead uniformity lest that type of rigidity in the shape of rule of law is introduced through a new form of testimonial tyranny making justice a casualty. Courts cannot cling to a fossil formula and insist upon corroboration even if, taken as a whole, the case spoken of by the victim of sex crime strikes the judicial mind as probable". [Emphasis added]

The judge in the Tejpal case took note in her judgment of the observations made by the apex court in Gurmit Singh on how to approach a case of sexual offence against a woman, but proceeded by defying every single observation of the said judgment in both letter and spirit.

There is no dearth of judgments of the Supreme Court [for instance, Gurmit Singh, State of Uttar Pradesh vs. Munshi (AIR 2009 SC 370), Narender Kumar vs. State (NCT of Delhi) (2012 7 SCC 171)], where the Supreme Court has clearly held that past conduct or previous sexual experience or life style of the prosecutrix has no relevance while dealing with any specific allegation of rape/sexual assault.

The judgment in the Tejpal case categorically took note of this settled legal position, but then in complete defiance of the same, it elaborately lays out phone messages of the prosecutrix with her friends with exceptional detailing by disclosing names of the groups, her friends and contacts, the messages exchanged between them, her relationships, and statements by other witnesses about her relationships.

The judgment has gone at length discussing the evidence of witnesses referring to her personal choices of sexual interactions, as if the same has any bearing on the charges she made or as if it is necessary for the prosecutrix to establish that she had an unblemished character or past.

Much ink is spent by the judge to establish that the prosecutrix was a person with liberal approach and had past sexual experiences, as if it is permissible in law to test the prosecution case on this touchstone, or that it is permissible in law to discuss the past habits or lifestyle of the prosecutrix, or as if it was a trial against the prosecutrix to establish the character or sexual morality of the prosecutrix.

The judgment thus sets a wrong and dangerous precedent, which all future sexual assault-accused would look to take advantage of.

Going by this judgment, one may easily hold that a prosecutrix or a liberal woman can be raped or sexually molested or that she has no right to challenge her violation.

The legal position is clear that no woman can participate in a sexual encounter without her consent, else such encounter would be an offence in eye of law irrespective of the lifestyle, character or sexual practices of the said woman.

If the settled legal mandate of law and previous legal pronouncements in this regard had been followed by the judge, and all the material, repeated references and discussion about the character, past sexual experiences and life style of the prosecutrix were avoided in the judgment (which were all unnecessary and impermissible in law to mention, to begin with) then the length of the judgment would certainly have reduced by more than two-thirds.

Statutory provisions (Sections 228A of the IPC and Section 327 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973) and judgments of the Supreme Court [Gurmit Singh and Nipun Saxena & Anr. vs. Union of India & Ors., (2019) 2 SCC 703] clearly mandate that the disclosure of the identity of a victim of sexual offence is not permissible. Still, the judgment repeatedly disclosed the names of the friends, relatives and acquaintances of the prosecutrix, as well as her email address.

The judgment is basically an open book about the prosecutrix, her alleged character, her alleged life style, her alleged interactions, and her friends.

In the zest of proving the sexual immorality of the prosecutrix, the judge seems to have completely forgotten about existence of Section 53A inserted into the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, in 2013, post the barbaric Nirbhaya rape incident, which clearly says that "evidence of the character of the victim or of such person's previous sexual experience with any person shall not be relevant." [Emphasis added]

The judgment has surprisingly also not taken note of Section 114A of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, either, which clearly provides for presumption as to absence of consent in certain prosecution for rape. Had these provisions been taken notice of and placed proper reliance on, the judgment would not have proceeded on the principle that "the burden is, no doubt, on the prosecution to prove beyond reasonable doubt the offences alleged to have been committed by the accused and the onus does not shift".

This approach has been adopted when, on the face of the allegations, the case of the prosecutrix is squarely covered by section 114A of the Evidence Act, and thus entitled for the benefit of presumption. This is aided by the unconditional apology tendered in unequivocal terms by the accused, in which he says that it was a judgmental error and that he misunderstood the prosecutrix.

The very language of the apology clearly admits that the accused did some sexual mischief which was not consented to by the prosecutrix, and that the said act had violated her sexually. Despite this apology in writing, which the accused never disowned, the judgment has given full acquittal to the accused.

Humiliating and torturous cross-examination of a victim of sexual offence or rape, and her treatment in the court during cross-examination by the defence lawyers, has been a major concern of all rights-conscious people. It has, time and again, received a lot of criticism even from the highest court of the country.

The Supreme Court in Gurmit Singh had observed that "some defence counsels adopt the strategy of continual questioning of the prosecutrix as to the details of the rape. The victim is required to repeat again and again the details of the rape incidents…" The Court ultimately held that:

"The Court … should not sit as a silent spectator while the victim of crime is being cross examined by the defence. It must effectively control the recording. … the court must … ensure that the cross examination is not made a means of harassment or causing humiliation to the victim of crime. A victim of rape, it must be remembered, has already undergone a traumatic experience …"

In the Tejpal case, the judge, despite above legal mandate, allowed scandalous, irrelevant, and torturous questions to be asked to the victim in her cross-examination that ran into nearly 700 pages.

Not only did the judge allow this marathon cross-examination where the defence betrayed all norms of decency and threw to dust all judicial dictates on how not to cross-examine a rape victim, but the judge has multiplied her trauma by repeatedly referring to those gory details in her judgement which should not have even been allowed to be asked by the defence lawyer to the victim, much less to place heavy reliance on the same in the judgment.

The victim was cross examined on fine detailing of the incident frame by frame as if it is humanly possible for a woman being sexually violated to be in the state to be able to notice all those details, and then be able to remember and then narrate them.

Here, one must find fault with the public prosecutor as well, who allowed this humiliation and torture upon the prosecutrix in the court room. A bare reading of the judgement reflects the plight of the prosecutrix, and the trauma which she must have underwent during her cross-examination. It must have not only shaken her confidence in the system, but such treatment with a well-educated and well-informed prosecutrix shakes confidence of others in courts as well.

The learned Judge treated the prosecutrix with great suspicion, while on the other hand the accused seems to have been afforded benefit of doubt. While reading the judgment it seemed to me as if the prosecutrix was being punished for daring to raise a voice against her violation, or that it was she who was facing the trial and not the accused.

The prejudiced approach of the judge against the prosecutrix is also clearly reflected from the fact that her education, her knowledge, her expertise, and the fact that she consulted eminent lawyers, all were construed against her by the judge.

Ironically, this judgment has come after the recent hue and cry in light of a Madras High Court order referring a rape victim to mediation in light of the offender agreeing to marry her, and a Madhya Pradesh High Court order granting bail to an accused subject to tying of rakhi to the prosecutrix. The issue was taken up by the Supreme Court in Aparna Bhat & Ors. vs. State of Madhya Pradesh & Anr. (2021 SCC OnLine SC 230), and guidelines were issued by in its judgment, wherein the court emphasised that sensitivity should be displayed at all times by judges, who should ensure that there is no traumatisation of the prosecutrix during the proceedings, or anything said during the arguments. Moreover, judges especially should not use any words, spoken or written, that would undermine or shake the confidence of the survivor in the fairness or impartiality of the court.

Clearly, this judgment qualifies to be remembered for all wrong reasons, for violating all settled legal principles which were to be adhered to while dealing with a case of sexual assault or rape.

Since this judgement has discussed the personal life of the victim, choices, and even the detailing of the incident at great length, it is necessary that this judgment is directed by the High Court to be taken off from all social media platforms and should not be allowed to any third party to take its certified copy from the court.

(Shobha Gupta is a lawyer at the Supreme Court of India. The views expressed are personal.)